[For basketball historians, it’s only natural to wonder who invented the jump shot, the behind-the-back pass, or really anything associated with the modern game. It’s also tough to find definitive answers to the invention question. For example, many people have claimed to be the originator of the jump shot, and the truth is all of them might be right. The jump shot may have arisen in multiple places around the country at different times. It’s always seemed to me that the better question is: Who popularized the jump shot and influenced others to give it an excited try?

The three-point shot might be different, though. The man who seems to have invented and pushed to popularize the three-pointer is clearly identified: Howard Hobson, the University of Oregon coaching great. He was behind a February 1945 game between Columbia and Fordham to experiment with a three-point shot and a two-point free throw. Records of this experimental game exist, such as this clip from the New York Times that specifically states, “For this novel encounter, sponsored by Howard Hobson, former Oregon coach, and Julian Rice, Columbia alumnus, a 21-foot arc was painted on both sides of the court. All field goals caged from a point beyond this circle netted 3 points instead of 2.”

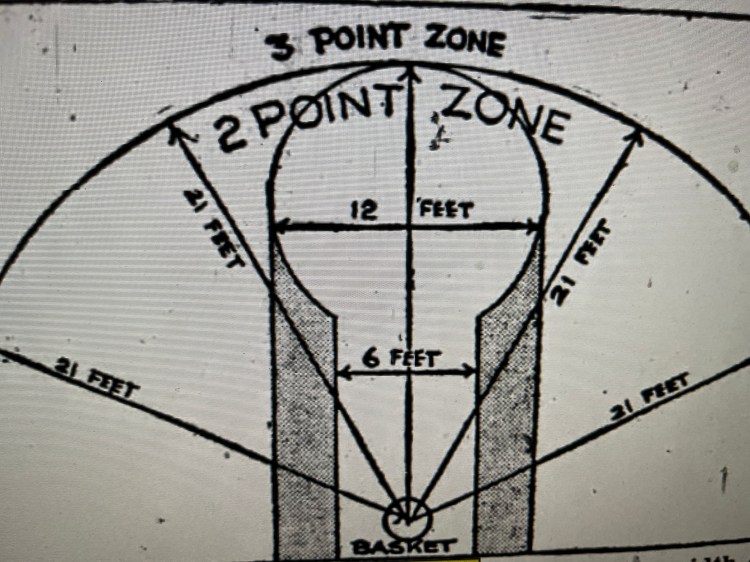

The New York Daily News also singles out Hobson in the run-up to the Columbia-Fordham game. “Hobson reasons that the threat of a three-point goal being scored against them will prompt a zone-defending team to come out farther toward midcourt and thus give the attacking team more room to operate in.” Young’s story even includes an illustration showing the court dimensions of the three-point shot.”

There are a few other stories that credit Hobson. Of course, that doesn’t eliminate the possibility that Hobson borrowed the idea from elsewhere. In the 1940s, when U.S. military service was a great mixing bowl of regional basketball styles and techniques, future coaches and players borrowed liberally from their tours of duty.

Even if Hobson borrowed the idea from a bunk mate or a coaching colleague who tried it back home, he clearly pondered the idea, studied it, and spent decades championing the three-pointer to the colleges and the pros. Wayne Thompson, who covered the Trail Blazers for years for the Oregonian, tells Hobson’s story in greater detail in this piece published in the magazine Pro/College Basketball Scene, 1979-80. The news peg for Thompson’s story was the three-point shot’s arrival in the NBA in 1979. One quick comment. Thompson’s story was a little stiff in places, and I did some very minor editing to help the lines bend a little. It’s still a little rigid here and there, but the information is definitely worth the read.]

****

World War II was winding down in Europe. MacArthur returned to Manilla as promised. A 260-pound Babe Ruth celebrated his 51st birthday with a case of beer. Golfer Sammy Snead smoked an eight-under-par 64 to lead the New Orleans Open.

Pro basketball? The National Basketball Association was unborn. But the three-point field goal—basketball’s version of a Babe Ruth home run, a Sammy Snead eagle shot, a war-ending missile—had just seen the light of day.

In a tiny gymnasium on the campus of New York’s Columbia University, a 42-year-old graduate student from Oregon was illustrating a revolutionary scoring plan for a game of basketball that was not yet ready to accept it.

Nevertheless, February 7, 1945 marked the birth of the three-point bomb in basketball—a ploy later used successfully by the American Basketball League in the late 1950s and into the early 1960s. And then it was rolled out again by the American Basketball Association in the late-1960s and into the 1970s.

The inventor of the three-point field goal, Hall of Fame basketball coach Howard Hobson, waited a long time to see his idea emerge from the realm of fancy and into American living rooms. After 34 years in an out of limbo, Hobson’s three-point dream has arrived in the NBA and its the one-on-one, slam dunk world.

“I’ve waited a long time for this,” says Hobson, now a spritely 76 years old, but still active in his letter-writing campaign to convince organized basketball officials at all levels to adopt his three-point field goal plan.

“I think the three-point field goal will go a long way in eliminating violence in the sport by combating the congestion under the basket. It will also prevent many pro teams from employing illegal zone defenses,” he said.

“But beyond all of that, the three-point shot will bring a new dimension back to the sport; it will create the same kind of excitement for basketball that baseball has with its home run. Who knows, the three-pointer may bring the two-hand set shot out of extinction. It went the way of the passenger pigeon when the one-hand push shot and jump shot were perfected,” he said.

While the NBA has adopted Hobson’s dream for the 1979-80 season, the skeptics still remain. Portland Trail Blazer coach Jack Ramsay, whose coaching style favors layups over five-footers and who personally detests any shot taken over 16 feet from the basket, is an opponent of the three-point goal.

In a friendly argument with Hobson, who attends many of the Trail Blazer home games, Ramsay said, “I don’t understand the logic of it. In baseball, a home run only counts for one run; a field goal in football is scored the same from the five-yard line as it is from the 50; soccer and hockey goals close to the net count the same on the scoreboard as screamers from 25 feet. So why count two points for a basket scored from within 23 feet and three points for one shot beyond that?”

Hobson, after waiting for 34 years, had the answer. “All hits in baseball aren’t rated equally. There’s the short hit—the single. A little longer one—a double. Then, there’s the triple. And if you hit the ball out of the park, it’s a home run. I’m not advocating that a 90-foot shot from one end of the court to the other account any more than the one from 23.”

The argument will continue, no doubt, throughout the NBA this season as games are won and lost by the three-point bomb. Some, most certainly, will be made closer and more exciting by it. But Hobson has already won his argument.

Hobson, a former head coach at Southern Oregon College, University of Oregon, and Yale University (with a career won-loss record of 485-291), conceived the idea for the three-point shot while working on his master’s thesis at Columbia in 1944. He observed and charted all the shots during 23 college basketball games at Madison Square Garden that season, discovering that the accuracy of shots taken outside the 21-foot mark was 18.6 percent, while shooters converted 29.4 percent inside the 21-foot mark.

He figured the longer shot could be worth 50 percent more than the shorter one. Hence, he would award three points for the 21-footer and beyond, and two points for those scored within his imaginary 21-foot arc.

Hobson’s research and lobbying of fellow coaches in the New York area resulted in the playing of the first revolutionary three-point field goal basketball game between Columbia and Fordham, February 7, 1945. The game was well-attended by students and officials of the Eastern intercollegiate rules body and New York metropolitan area coaches. Using the three-point shot more liberally than might be the case in a normal game, Columbia defeated Fordham, 73-58. Had the long shots not been counted for three points, Columbia would have won 62-49. In the game, Columbia made 11 long field goals for 33 of its points, while Fordham converted nine for 27 points.

The Hobson Plan induced its share of skeptics after the Fordham-Columbia game, but it also lured some support. City College of New York coach Nat Holman wanted to see the three-point goal tested for a year, just as the elimination of the infamous center jump was tried first by the Pacific Coast Conference before the rest of the nation’s colleges followed suit.

Howard Cann, coach of New York University, was particularly enthusiastic. “I think the coaches’ association research committee ought to get to work on it right away,” Cann told the New York Times in 1945. A pool of fans at the game showed 140 in favor of the three-point bomb, while 105 opposed it.

Armed with renewed enthusiasm, Hobson, who was on leave from Oregon, a basketball-minded school that Hobson led in 1939 to the first-ever NCAA tournament championship, continued to seek new showcases for his bomb. He found one at Camp Patrick Henry just before accepting a military assignment in Europe.

Hobson persuaded two army teams, Camp Patrick Henry and Newport News, to play his three -point game. Both teams employed man-to-man defense—not conducive to three-point shooting comfort—and Patrick Henry built a 17-point lead with six minutes to go when Newport News bounded back with three straight three-point bombs, finally losing in a close finish, 53-48.

During the 1940s, Hobson conducted 15 exhibitions using the three-point shot. From those early trials, the three-point field goal exited for 10 more years. Until Abe Saperstein, who gained his reputation with the Harlem Globetrotters, plucked it off the shelf for a brief trial in the short-lived American Basketball League. Saperstein, however, increased the distance for the three-pointers beyond 25 feet because there were still some players popping two-hand set shots, and they could pop the nets with the accuracy from 35 to 40 feet away.

“Unfortunately,” recalled Hobson, “that spectacular shot—the real home run of basketball— was placed on the endangered species list when our study of percentages showed that it did not pay to take longer shots.”

When the ABA picked up the three-pointer, ushering in the remarkable era of such a long bombers as Louie Dampier, Darrell Carrier, and Bill Keller, it chose a 23-foot arc, which Hobson thinks is in range of effectiveness for most players today.

When the NBA Rules Committee adopted its three-point play this summer, it didn’t pick the dimensions casually. Hobson had written several letters to NBA commissioner Larry O’Brien urging the NBA to adopt shorter distances. “My study and observations still indicate that 23 feet would be a better distance than 25 feet for the NBA right now,” Hobson wrote in his letter to O’Brien.

The NBA, with Hobson’s urging, has adopted a three-point arc that measures 22 feet from the basket at the baseline corners to a maximum length of 23.9 feet at the top of the key. Swish! Hobson’s Columbia-Fordham dream comes true.

Hobson’s recommendation of a 23-foot three-point shot arc was not plucked out of a hat. “We must realize that too great a distance will not drive the defense out, as the percentage will be too small; too short a distance, on the other hand, will not relieve the congestion under the basket. Besides all that, I think 25 feet is out of the range of most NBA players,” said Hobson, who just happens to have another study to prove it.

Hobson charted eight Trail Blazer games last season and discovered that only two shots—both unsuccessful—were taken beyond 24 feet out of the 1,340 shot attempts by both teams. Fifty-three shots were taken beyond 21 feet with 15 made for a 28.3 percentage. Inside of 21 feet, 581 of 1,287 attempts were made for a 45.1 percentage. Hobson said his original idea was to score one point for a basket out to 12 feet, two points up to 24, and three points beyond 24. “That would have been too complicated,” he said.

It is Hobson’s observation, based on coaching and analyzing basketball games since 1923, that “except for interceptions and fastbreak goals, the game is played within a radius of about 23 feet from the basket. Players are bigger now, and when 10 of them get into such a small area, bodily contact leading to violence is bound to occur.

“The three-point plan will draw the defense out, decrease the use of illegal zone defenses, develop specialty players—home run hitters—who can come off the bench and raise havoc with the team sitting on a lead in the closing minutes of the game, and will relieve a lot of the congestion under the basket,” Hobson says.

“It will even help some of the big centers, like Artis Gilmore and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, by giving them more room to maneuver, while it should help the little guys with the good outside shot to find jobs in pro basketball,” Hobson said.

Perhaps the real reason Hobson has struggled so long and so hard to sell his extra point for a 24-foot bomb is to resurrect the two-hand set shot as part of basketball’s offensive weaponry. The shot that made famous Dolph Schayes, Slater Martin, Kenny Sailors, Bobby Wanzer, Bob Davies, and other stars of the 1940s and 1950s, could, like the whooping crane, be nursed back to life.

“I saw in my lifetime, the birth of the one-hand shot. It did much to open up scoring; it is accurate, but my studies of over 250 games over a 13-year period show that the range of the one-hand shot is only about 24 feet. Hank Luisetti of Stanford revolutionized the game with the one-hand shot, which, for a while, was used alternately with the two-handed shot,” Hobson said.

But gradually the game evolved into a one-handed shot affair exclusively, with players in grade school and high school unexposed to two-handed set shooting. My hope has been that if I could get the NBA to adopt a three-point play, then prep and college teams might follow suit. That way, the kids on the playground would not only practice their slam-dunk moves, but maybe they would start taking up the two-handed, 25-foot bomb again,” Hobson winked.

“I think it will give the game the shot in the arm it’s looking for,” Hobson added. “The fans in the ABA went crazy over it, just like the fans at the Columbia-Fordham game 34 years ago who cried out, ‘Three’ every time a guard dribbled the ball over the midcourt.

“Or like the time in the ABA when Dallas led Indiana, 118-116, with two seconds left, and Indiana’s Jerry Harkness uncorked a two-handed, 92-foot bomb for three points that gave the Pacers the victory. That kind of long-range excitement has been missing from basketball for far too many years,” he said.

It has returned this fall in the NBA, adding new dimensions for Lloyd Free, Randy Smith, Pete Maravich, Rick Barry, Louie Dampier, and Freddie Brown to shoot from. And Howard “Hobby” Hobson will be charting the results of his brainchild—a proud parent just waiting to see which player discovers first that two hands are better than one . . . from 23.9 feet.

The next change is to make free-throws more exciting. All free-throws would be taken after the game ends. Shag has been fouled four times. His team is trailing by three points after regulation.

If he makes all four foul shots. His team wins, yet the game score after regulation, his team was

behind. One free throw could decide the game. All players who were fouled, must take their foul

shots in this manner,

The game has speeded up. Needed is a running clock, no time-outs, players join the action on the

run, for substitution purpose. The action only stops when there is a foul. They are basically playing this type of basketball in the NBA play-offs.

Dennis Rash

LikeLike