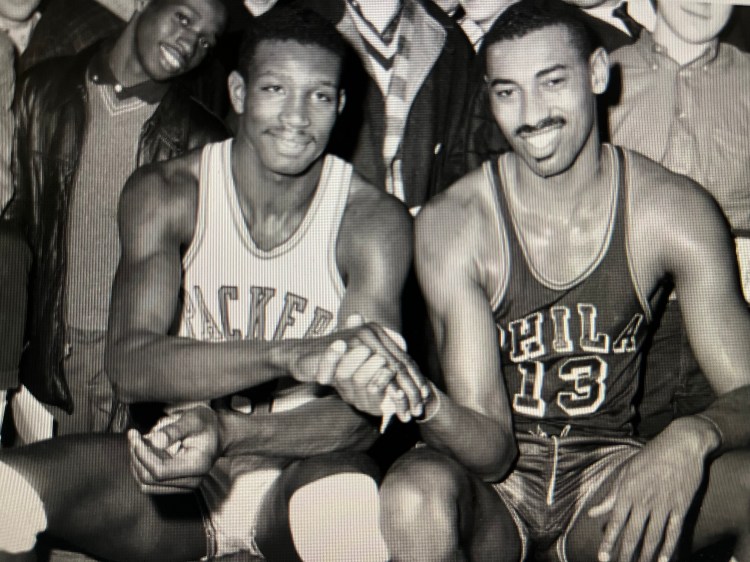

[In the early 1960s, the NBA briefly had its Big Three of big men. Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell, and . . . Walter Bellamy. Big Bell. Or, just “Bells,” the star of the Chicago Packers-turned-Zephyrs-turned-Baltimore Bullets. “Deadly with a hook or jump shot,” read a capsule description of his game. “Appears awkward, but is surprisingly fast and agile for someone his treetop-tall size.” Bellamy’s acclaim waned over his NBA career, thrusting him out of the Big Three by the mid- to-late 1960s. “At center once again,” lamented a basketball magazine in 1969, “is the enigmatic Walter Bellamy, on some nights he can challenge Russell and Chamberlain and on other nights can fall flat.”

Even so, Bellamy and his big personality remained a big hit with reporters. Bellamy’s charm unfortunately isn’t on full display here in this article from the February 1963 issue of SPORT Magazine. But writer Bill Furlong does capture Bellamy’s rise into the Big Three as a member of the Chicago Zephyrs. When’s the last time you read an article of the Zephyrs. Well, here you go.]

****

At noon, the fieldhouse was as dark and gloomy as a mausoleum and dust curled up from around the edges of the basketball court. On the steps down to the locker room shone a halo of a single light. “Seems like I spend half my life down here,” said Walter Bellamy, as he wandered into the training room. He’d hurt the metatarsal bone in his right foot a few days earlier, and now he was wearing a special protective pad in his white basketball shoe.

He sat down and pulled a small jar bearing a Kraft food label out of a blue bag. He dipped into it and applied the clear, viscous liquid—apparently a glue—to a pad for his shoe. Around him swirled the inconsequential small talk of the professional athlete, relaxing after a workout.

“I think taking the ‘L’ is nicer’n driving, anyway,” said one member of the Chicago Zephyrs. Another nodded and tried the handle in a shower stall. It was stuck. “Well, I guess we’d better use the others,” he said. He threw a towel over his shoulder and walked out.

Si Green and Mel Nowell, guards for the Zephyrs, walked in, and Bellamy looked up. “Lot of vicious picks out there today,” he said of the workout. “Vicious picks.” Nowell looked up in surprise as Bellamy slipped into a shoe and walked cautiously around the locker room. “Man,” said Nowell, “you come down like you weigh 500 pounds, and you talk about vicious picks?”

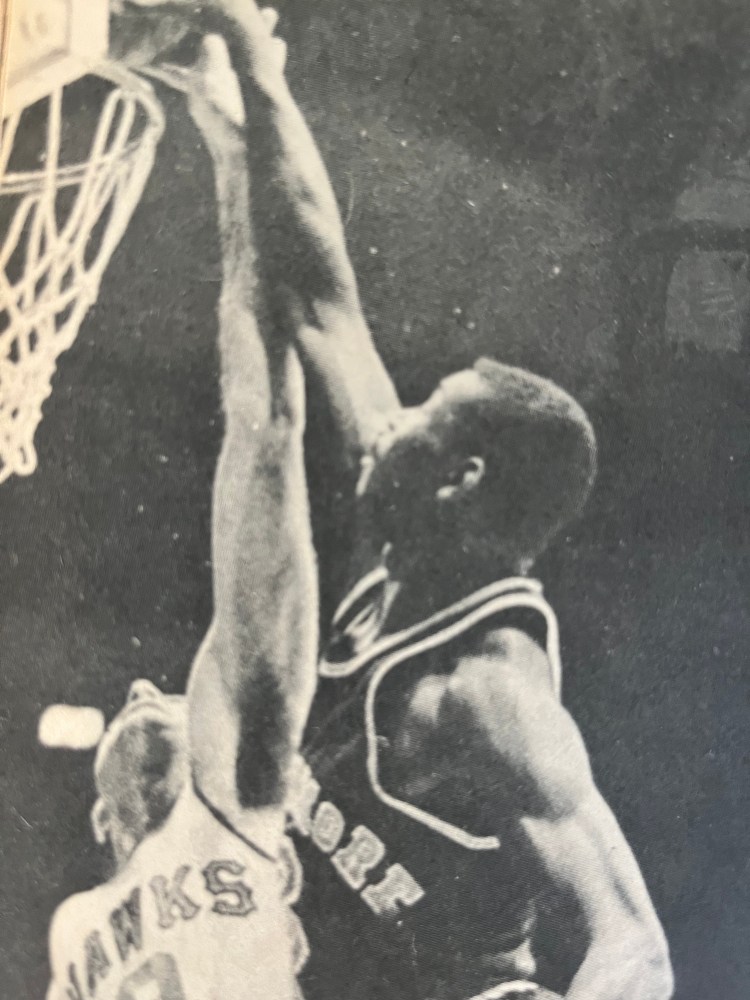

When he said “vicious picks,” there was in Bellamy’s voice that subtle tone of the man at war—the man who must warn even his teammates that he knows the signals of war. For Walt Bellamy is engaged in the battle of pro basketball, and it is his habit in war—as in life—to keep everybody a little off-balance, even if they are on his side. He is 6-10 and weighs 230 pounds, and his profession, almost predestined by his size, is playing basketball. To play it well, he wages psychological as well as physical warfare. The result: Last season—his first in pro basketball—Walt set a record for the National Basketball Association with a field-goal percentage of .513, and his 2,495 points left him only five short of becoming the second man in NBA history to score 2,500 points. (The first man was Wilt Chamberlain.)

Today—though he lacks Wilt’s height by three inches—Walt Bellamy is widely regarded as the “new” Wilt Chamberlain. He is very, very strong. (Last summer, after learning the bone-rattling rigors of life in the NBA, he worked out with weights to build his strength.) He is very, very agile—“as agile,” say his coach Jack McMahon, “as a guard who’s only 6-2 or 6-3.” As a result, he dominates the backboards like a cougar at bay. “He hits you,” says one teammate after a scrimmage against Walt, “like he’s mad at your whole family.”

Furthermore, he is very fast—“the fastest big man in the league,” says McMahon. “And he has a soft-and-delicate shooting touch.” “He’s got the best ‘touch’ of all the men in the league,” says a teammate—which means he doesn’t have to stand near the basket, dunking shots, like a man with a yo-yo, but can move to the outside and arch in longer shots with great grace and precision.

It was not always thus. At first, the violence of the NBA seemed to shock him. “The first few games he played up here,” recalls one observer, “he looked like he was lost.” In Bellamy’s first game against the Warriors, his first nine shots were blocked by Chamberlain. “He was so frustrated that he didn’t know what to do,” said Jim Pollard, then coach of the Chicago Packers (this season, they’ve changed their name as well as their coaches). But Bellamy learns quickly. The second time he played against the Warriors, Bellamy scored 45 points and Chamberlain scored 50.

Similarly, the first time Bellamy and Bill Russell hooked up, Russell outscored Bellamy, 28-17, and dominated the boards. Walt scored only once in the last period. “When he started, Walt was scared to death of Chamberlain and Russell,” said Celtic coach Red Auerbach after the game. “Now he’s only scared to death of Russell.” The next time they met, Bellamy outscored Russell, 35 to 14, and outrebounded him, 30-18. At the end of the season, Walt was second in the league scoring and first in the Rookie-of-the-Year election. “There was a boy who really improved,” said Chamberlain. “I’d say 300, maybe 400, percent.”

When he left Indiana University in 1961, Walt Bellamy was hardly prepared for professional basketball. He was a lanky youth, who walked with derriere out and shoulders back. He wore a quizzical, cold look on his face. “He doesn’t like to show his emotion,” said Pollard. “He doesn’t want people to know that he’s shook up, that he’s scared.”

He had reason for his fright. He couldn’t play defense; he still can’t play it exceptionally well. His college offense hadn’t prepared him for the pros. “Indiana played fast-break basketball. He’d rebound, pass out, and the guards would be down the court shooting before he could get into position,” recalls one of his former Big Ten rivals. When he did get into position, he needed only a narrow range of shots to be effective. He was big and strong. (He played only two games a week, not a strength-sapping pro schedule), and he got into position often enough to use his size and strength to pile up relatively easy points and an All-America rating.

But he had the potential to do more—to shoot from further back, to learn to rebound the rough, pro way—and he had the good fortune of joining a pro team, that could afford the luxury of letting him develop the potential immediately. Chicago was a new team, put together with NBA discards. The club had to develop new stars quickly, not let men of potential ease into the lineup as happens on the Celtics, say, or the Lakers. “Walt was the only man with real scoring strength, and he didn’t have anybody to rebound with him,” says Pollard.

So Walt had to play—and he had to learn as he played. “I learned more in 12 games as a pro than I did in three years in college,” said Bellamy in mid-season. Among the things he learned were:

The difference in quality—“For the first time in my life,” said Bellamy, “I’m playing against guys who are as big or bigger than I am. Wilt is 7-1. Walt Dukes is about 7-feet tall, and Swede Halbrook is 7-3. And the quality of shooting in the NBA is amazing. In college, you could concentrate on two or three good shooters to a team. In pro ball, everybody’s a good shot.”

The difference in contact—“I expected the rougher contact,” said Bellamy. “Sure, it can get pretty rugged under the boards, but I don’t look around and expect to hear the whistle every time I get bumped, like in school.”

The difference in the stamina needed—“At Indiana,” said Bellamy, “we played 24 games in an entire season; now we play 80 games in a season.” In fact, Chicago played 17 games last December alone and twice had streaks of playing eight games in nine days. Pollard knew that the pace was a rugged one to adjust just to—but he had nobody else to compare with Bellamy. He settled for a technique of benching Bellamy in the last minute or so of every quarter in order to give the center two or three consecutive minutes of rest in each quarter. One big factor was that Bellamy—from his “fast-break” days at Indiana—frequently raced up and down the court faster than other centers in the NBA. “Walt used to run a little too much at first, but we’re trying to teach him to pace himself,” said Pollard at mid-season.

Pace is still a problem with Bellamy. “I found other players doing it, but I’m still trying to master it,” he says. Some critics feel that he paces himself according to the opposition—that he plays superbly against tough opposition and let’s down against mediocre competition. But now, with Jack McMahon, the new coach of the Chicago club, pace is less important. “There’s no such thing as a hard 35 minutes and an easy five minutes in this game,” says McMahon. And he was tending to use Bellamy for 42 to 48 minutes a game, not simply for 40.

****

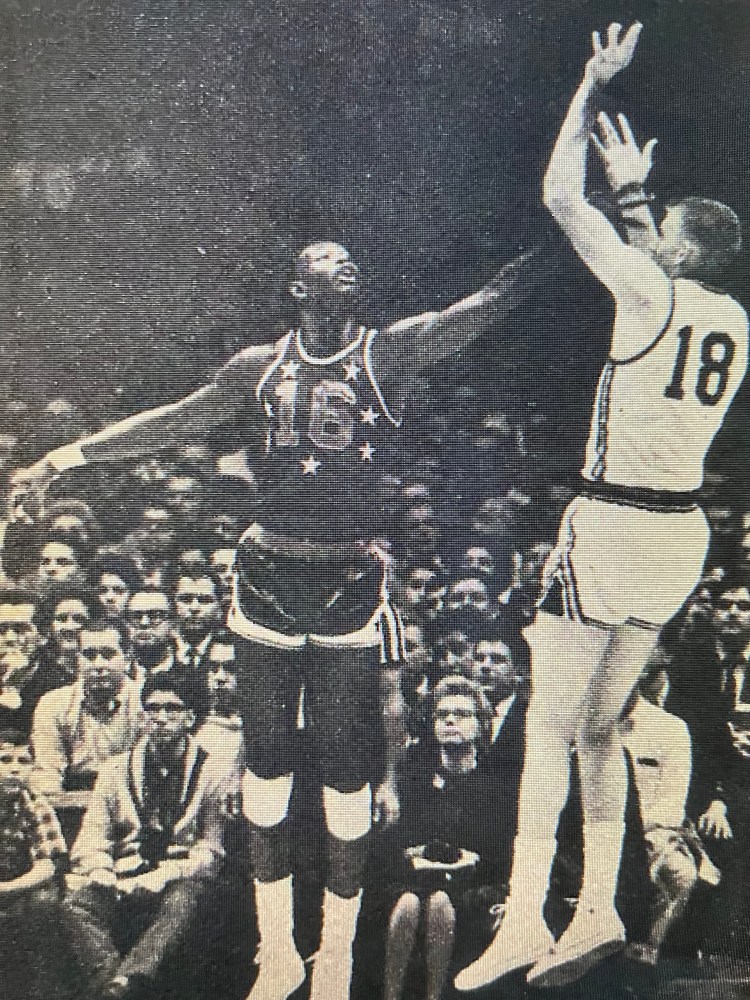

There was much else to learn in the NBA. He had to learn the talents of the opposition, techniques on both offense and defense. “With Wilt and Russell, you have to give ground and play more and more to the outside,” Bellamy says. “They tend to play the hole to protect the defensive backboards.”

On offense, he found that his college shots were inadequate to the competition in the NBA. So he developed a hook shot from 12 to 15 feet out. They gave him greater versatility and greater scoring punch.

Most of all, he had to learn to get the proper position on the court. “Offensively, he must learn to hold his position under the basket,” said Jim Pollard. “For his size and quickness, he’s had too many passes taken away because he’s been bumped out of position.” As time went by, Bellamy figured that it was not simply a matter of standing still in one position. “The defensive opponent will not let you stay there,” Walt says. “You have to juggle with him for position, and juggling tires you out.”

He found also that his rivals were alert to every move, to every subconscious habit. In his early days in the league, he always turned to his right to get off a particular shot. “Bill Russell tipped me off,” he has said, “so now sometimes I fake to my right and turn to my left to make the shot. On still other occasions, he found players expecting him to turn left at a particular point on the floor were able to break for the basket and be a step closer to the rebound.

He was working virtually alone. Chicago had no major scoring threat from the outside—guard Bob Leonard was second in scoring with 1,125 points, half of Walt’s booty—and so the rival NBA teams could sag three or four men back onto Bellamy in an effort to check him. And nobody else on the team could help him on rebounds. Bellamy grabbed 1,500 rebounds for an average of 19 a game—third in the league behind Chamberlain and Russell. Only one other man on the team has as many as 600 rebounds—and he was a substitute center, Charley Tyra.

One result: despite Bellamy’s effort, Chicago lost 62 games last season, an NBA record. The team didn’t win a game from the Philadelphia (now San Francisco) Warriors; it won only one from Boston, one from Syracuse, one from Cincinnati. It finished 11 games out of fourth place in the Western Division, 19 games out of third place. Under the circumstances, there was considerable danger that the Chicagoans—including Bellamy—would learn to accept the fact that they’d be beaten. Bellamy liked to apply “psychology” to the situation.

“I don’t consider on any night that we’re going to get defeated,” he said. “On any given night, it didn’t make any difference who we were going to play. If I overrated an opponent and thought we were sure to be beaten, then I might defeat myself.”

****

Consequently, the word was soon out that the big rookie was as unstoppable as water running downhill. Opponents didn’t set up defenses against him under the bucket or even in midcourt; they began defensing him as soon as he entered the west gate of the basketball arena. Ray Meyer, coach at DePaul, said, “He has quick reactions and good timing. He has good hands, and he follows the ball well in flight. Once he learns defense, he’s going to be one of the great ones in the game.”

As the current season groped toward maturity, Bellamy and the Zephyrs seemed more effective. For one thing, the Zephyrs had some outside shooting in the occasional artistry of Terry Dischinger—who won’t join the team full-time until January 20—and of Johnny Cox, who came to them from the American Basketball League. That made other teams more cautious about sagging in to defend against Walt.

For another, Bellamy was still learning about how to wage the war of professional basketball. He still had much to learn about defense—and coach Jack McMahon is a man who emphasizes defense. He can, for example, bend over and bump a defender with his derriere, then stand erect and bump him off-balance again with his shoulders. “His responsibility is to get his position and hold it,” says McMahon. “Our responsibility is to get the ball into him. He’s also learning to turn into the basket to get his shot instead of giving ground and dropping away to get the shot. This way he draws the fouls, in addition to getting the basket,” says McMahon.

And he’s also worked on his free throws. Last year, he hit for a percentage of .636 on free throws, while the great free-throw shooters of the NBA—who are usually also the men who are simply great shooters—ranged from .625 to .896. During the summer, Bellamy shot 200 free throws per day in an effort to improve his accuracy. In one game early in the season, he hit 15 out of 16; in another, he hit eight out of nine. The rest of the league was learning that he could do damage at the free-throw line. In an exhibition game, the Detroit Pistons fouled him 13 times in the act of shooting, and Bellamy sank 20 of 26 free throws. “Well,” said coach Deck McGuire of Detroit, ”we can’t stop him that way anymore.”

The environment that prepared Walt Bellamy for tough, professional basketball was, strangely, a feminine one. He was born 23 years ago and grew up in New Bern, North Carolina, an industrial and fishing town with a population of 16,500 on the Neuse River. His father was a tall man—6-5. Walt, an only child, was raised with his mother and his mother’s family. They were named Jones, and they lived on Jones Street in New Bern.

“Bob Mann, who played football at Michigan, was from our neighborhood,” Walt has said, “and there were a lot of fellows who went to [Black] schools like Shaw University, Hampton Institute, and Virginia Union. “At home, Walt was influenced by the all-girl family of his mother. On the playground and in school, he was influenced most by Simon Coates, the coach at J.T. Barber High School. “He taught us the value of athletics in terms of later environment,” says Walt. “To prepare for athletics, you’ve got to control your physical self, your mental self, and your spiritual self. He wanted all his athletes to be prepared scholastically, but most of all, he taught us to be competitors on and off the field.”

Walt was always tall for his age—“but when I was 14 or so,” he says, “I shot up from 6-1 to 6-5 all of a sudden.” He’d started playing basketball when he was in seventh grade, but, like a good many other youngsters who grew precociously, he lacked coordination. “The kids who were shorter than I was were much better basketball players,” he has said. “It would irritate me when I was dribbling along and some little kid came up and batted the ball away from me.”

In high school, Walt played end in football and center in basketball. He was All-State in both sports. His team won a state championship in football and was third in the state in basketball. But athletics were not enough. His grandmother Rosa and his Aunt Alberta told him repeatedly that he needed an education to make something of himself. Just where to get it became clear the summer after he graduated from high school.

****

Simon Coates had been studying for his master’s degree in education at Indiana University during the summer. He told the coaching staff, headed by. Branch McCracken, of the boy who had grown so swiftly in New Bern and had earned an All-State rating. He liked it, and, although there was some doubt over his academic standards, he was admitted to the university. Nobody told him explicitly to give up playing football; it was simply suggested to him that playing two sports and keeping up his grades in the Big Ten was a highly demanding task.

“I would have liked to play football at Indiana,” Bellamy has said—but risking a great basketball player in a football game was as likable to coach McCracken as a case of gout. So Bellamy became a basketball player—of sorts. “I couldn’t even communicate with him at first,” McCracken has said. “He couldn’t even talk so I could understand him. He wasn’t aggressive, and he didn’t have a single good shot.”

But he did have great hands—“the biggest I’d seen in more than 25 years of coaching basketball,” said McCracken—he tended to hold the basketball in the heel of his hand and wrap his fingers around it, as if it were a tennis ball. But he had guts. At one point in his freshman year, he was caught in the throat with an elbow. For a few moments, the blow disabled him. When he was able to walk, he insisted on staying in the scrimmage—and, in the next few minutes, he scored eight straight baskets. “That’s when I knew he had it inside,” McCracken has said.

Bellamy enjoyed his best years as a sophomore and a junior at Indiana. “We had a good freshman squad that got together with a sophomore team when it was in his junior year,” he says. In 1958-59, as a sophomore, Bellamy attempted 181 field goals and scored 95. He led the Big Ten in field-goal percentage with .525. The next year, he scored 537 points and helped Indiana finish second in the conference behind Ohio State. In his senior year, Bellamy faded a little—some say because of the departure of two key players from the Indiana squad, some say because of those subtle deep-set qualities in his nature that arouse him only when the opportunity seems brightest (Indiana had little chance of winning the title, and everybody knew it).

At the same time, Bellamy was becoming a trifle more interested in business than physical education, the subject he was majoring in. He also was interested in marrying Helen Ragland, a North Carolina girl who attended Indiana with him.

Today, Walt’s business is basketball, and Helen’s is education (she is now Mrs. Bellamy). She teaches in the Chicago public school system and relays myriad questions home from her second-grade youngsters at Mark Sheridan School. “Like what do I eat, how much do I sleep, and who are the toughest players?” says Walt.

Home for the Bellamys is an apartment in an expensive, modern building near the University of Chicago. His first year in the NBA left Walt a wealthy man—and anxious to become wealthier. His rookie salary of $22,500 was supplemented by a $1,500 bonus. As a 1962-63 campaign neared, he demanded a $10,000 raise. He didn’t get it. Instead, the Zephyrs offered him $82,500 for a three-year contract. He turned it down; he hopes to do well enough to earn considerably more than that. So the Zephyrs finally signed him for $27,500.

The money he makes is considerable salve for the aches and bruises that he absorbs working at his job. At a workout a while ago, a gash was opened on his left wrist. “I think it was from somebody wearing a ring,” he said as a trainer bandaged the wound. “Sometimes,” Walt said quietly, in the tone of a man adjusted to his trade, “something just seems to happen to me every day.”