[In 1988, Billy Cunningham still ranked among Philadelphia’s most-popular sports heroes. He was remembered as the 76ers’ incomparable sixth man of the late 1960s, the high-scoring face of the franchise and perennial NBA all-star during the early 1970s, and the crafty coach who led “their Sixers” to a league championship in the early 1980s.

Here, freelance writer Jim Nechas sits down with Cunningham to talk basketball and, probably at the request of his editor and under the influence of a Bass ale, steers the latter part of the conversation to the state of the 1987-88 Philadelphia 76ers. Bad choice. At least for a basketball junkie like me flipping through the article some decades later. Billy C. was no longer affiliated with the 76ers and had no real inside dirt to offer Nechas and his readers. Who wouldn’t rather hear Billy C. confess a whole lot more about the ups and downs of his star-studded NBA journey, both as a player and a coach?

That quibble aside, what follows is well-written, well-structured, and offers a thoughtful glimpse into the world of Billy Cunningham in the late 1980s. If you were ever a fan of Billy C., you will definitely enjoy this article. It ran in the June/July 1988 issue of the magazine Philly Sport.]

****

I’m sitting outside Billy Cunningham’s Gladwyne home—45 minutes earlier than I was supposed to be—and wondering how many neighbors have called the police to complain about the strange guy and his declasse car at the bottom of this long cul-de-sac.

Maybe it’s the neighborhood, which calls its subdivisions by Welsh names like Bryn Tyddyn that are meant to recall its more venerable Main Line neighbor, Bryn Mawr. Or maybe I’m feeling conspicuous, because I amhere to case the joint, to find out how this ex-76er great lives and what he’s thinking about these days.

There are lots of steep mansard roofs and herringbone brickwork in Billy C’s neighborhood, lots of labor-intensive touches, and heating-bill-be-damned additions that tell a visitor like me that he doesn’t belong here. Still, in the midst (or, actually, at the end of) these hyper-dressed tract homes, Gatsby pretenders, and unmowable lawns, the Cunningham house is pleasant. It hides its light a bit and seems friendly.

Billy’s house is a big (but new) French country manor with a strangely anthropomorphic look. That is, there is a row of windows set across the second story, each under its own eyebrow lintel and peeking from beneath the hat-like roof. There’s also a nose bump down the center of the place to contain the double doors and a funny grillwork that looks like Ben Turpin’s mustache.

This quizzical house is shaded by a mixture of mature, ivy-shrouded trees and a few trucked-in numbers. Nestled in among the mountain laurel and rhododendron is a turnaround drive, a Lincoln Town Car, and a GMC Jimmy. Out back, there’s a tennis court surrounded by a big, double-height cyclone fence, painted a disappearing black, and a satellite dish. There are pheasants on Billy Cunningham’s fiberglass mailbox.

So, what the hell, I knocked, and I’m greeted by Sondra Cunningham, Billy’s wife (his family includes daughters Stephanie, 18, and Heather, 14), who tells me that he’s still upstairs—at 10 A.M.—and asks me to have a seat in the living room, which I do.

I can’t see Billy in this room. There are lots of low-to-the-floor, puffy upholstered pieces in wine and blue, some fragile, bow-legged, chairs, and, overall, an expanse of sink-down white carpet that’s like walking on the beach. Across the room and up a couple of steps, I can see a bow-legged desk that matches the chairs around me, a few trophies and basketballs, and a team picture or two. But nothing down here seems chosen to complement Billy’s towering scale.

Certainly not the graceful curving wall that separates the living room from the study and is laden with a collection of decorator favorites: a covey of stiff porcelain birds, baskets of powdery porcelain flowers, and an array of brand-new and significant books, all of them bound in maroon leather and stamped in gold. Just as I’m trying to read the titles, Billy comes in and ends my speculation about the room by completely filling it.

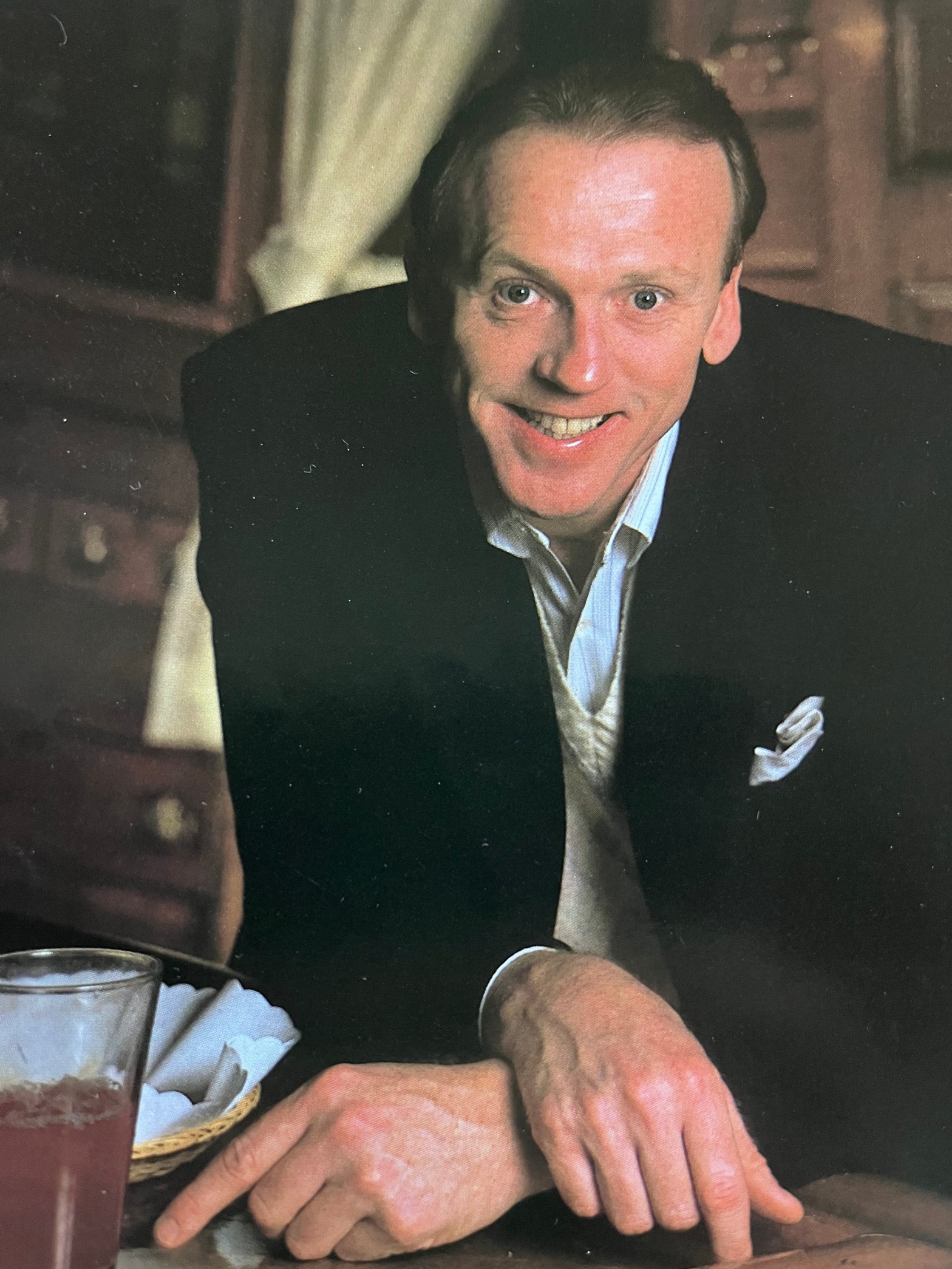

He’s 6’6” and looks a little thicker than I remember from his coaching days three years ago, but he’s still what everybody I know would call thin. At age 44, he also looks a little older than he did then, with a little less hair, now turning the color of cloudy brass, but he’s still got the look of fresh (and maybe skittish) intelligence that flashed from his eyes in the 1960s when he was The Kangaroo Kid.

Today, he’s wearing a shades-of-gray Nike warm-up suit and a pair of bright-white, size 12 ½ Nike trainers, which aren’t laced. His trouser legs flap from their open zippers, and he chugs into the room—carrying a big mug of coffee—with that curious stiff-legged walk-cum-run that guys who are good use to let you know that they are good. You know the one, that flat-footed shuffle with pumping elbows that somehow reveals the physical cost of stardom and belies the grace that comes with it. What we’re seeing right now, of course, is a scaled-down, living-room version of this famous amble, one that’s been modified still further by the fact that Billy, maybe like all very tall men entering middle age, has begun to bend a tiny bit at the waist and looks sort of like a jackknife about to close. Still, the signs of age rest very lightly on him.

Standing, we say hello, and I ask him where he would be most comfortable in this room of cloud-like pillows and creamy wallpaper. He looks around (pretty much as I had) and says, “Let’s go down to the basement.” Billy, it seems, doesn’t feel altogether at home at home, a fate people who travel for a living share.

****

Billy Cunningham’s basement, unlike Billy Cunningham’s living room, looks like it was made for him. Despite the lowered ceiling, the burnt-out down lights, and the shag carpet, there are huge tub chairs that seem capable of accepting his legs, a big Sony TV, a VCR, and maybe 50 to 100 game tapes left over from his days as head of the 76ers.

I first saw Billy C. in 1966, which was both his and my first year in Philly. He had been hired as the sixth man on a great Sixer team at the same time I was trying to get through graduate school at Penn. As sixth man, Billy’s job was to give sagging players a rest, to provide an instant infusion of points, to stop a run by the opposing team, to change the tempo at the game.

In those days, the Sixers played at Convention Hall, which is sort of down the road from where Penn’s English department used to be, and so at least once a week my first wife and I would cross the street to see the guys play. We were poor, and it was cheap. General admission back then was four dollars a head, and Ladies’ Night—Tuesday, I think—always brought my wife’s ticket down to two.

Anyway, we enjoyed Billy’s play in those early days, because, as that sixth man, he was a maniac—going up four, five times on the offensive boards for a tip-in, getting faked off his feet on defense and still managing to come down and go up again for the block. The crowds were always loud in that echoey old barn, but they would positively thunder when The Kangaroo Kid came in for Chet Walker or Luke Jackson. Everybody knew that the pace would pick up, that there’d be a flurry of points scored. It was fun, of course, to watch Chamberlain and Jackson spin like falling trees on their way to the basket, or to marvel at Walker’s puppet-on-a-string dances, but those guys were too strong, too slick, too smart to be candidates for hero worship. But Billy was just right; he seemed (then) to get by on energy and youth alone; he was pure playground, and Philadelphians have never had any trouble identifying with this reckless jumping jack.

Twenty-two years later, I wondered what memories endured—from his introduction to the game on the playgrounds of Brooklyn to the playing courts at the University of North Carolina to his stints for the Sixers as a player and coach, I switched on the tape recorder.

The Basement Tapes

When I first saw you play with the Sixers, you were a rookie in the NBA and maybe the best sixth man in the league. Was it difficult for you to give up the starter’s role you had in college?

Not with that team, because it was so talented, you know, when you have Luke Jackson and Chet Walker playing in front of you. I would think that it might have been more difficult for me at that time, young, thinking that starting is the most important thing, if I had been on a poorer team. But when you’re playing on a team that’s either number one or number two, I realized that the important thing was that you were getting your minutes and were being productive on the court. So I could deal with it.

When you had to retire nine years later, did you miss playing a great deal?

You know, it was one of those situations where everything was very easy. You tear your knee up, and the doctor says you’re not going to have a chance. You give it a try. You try to make it in training camp the next year, and the knee just keeps popping out. It made it very easy. I never had to ask myself all those questions: Is it the coach’s fault that I’m not playing more? Am I getting older? It was just clean, cut, and dried. Hey, it’s over with. You’ve got to move on with your life.

Did coaching immediately come to mind as the next step?

No, because I didn’t realize how much I’d eventually miss the game. I was involved in some other business ventures: I had a travel agency, I was involved with CBS, and I was doing some other things. I was very busy, and until I was asked to coach, it really never went through my mind. And then all of a sudden, when I got the phone call and talked to Sondra about it, I realized how much I missed this game. The coaching offer was a perfect situation. It seemed secure. I was in Philadelphia. Why not give it a try? I didn’t know what was going to happen, what kind of coach I’d be, but I knew one thing: I had no experience in doing it! I knew all the players, but I was still scared to death.

Were you good at it right away?

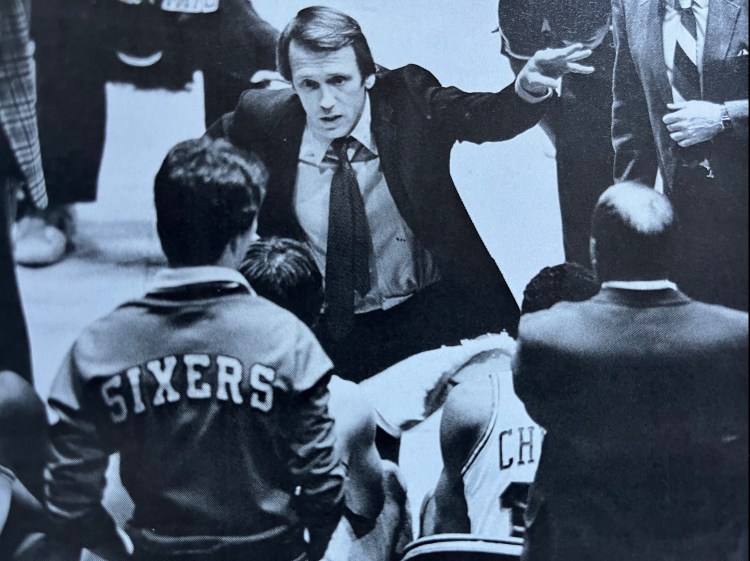

I liked it immediately, because I was in the action making some decisions. And I was very fortunate to have Jack McMahon and Chuck Daly with me. That was well over 50 years of basketball coaching experience on the bench with me, and they were very helpful in my growth. Drawing on their knowledge helped me put my personality into that basketball team.

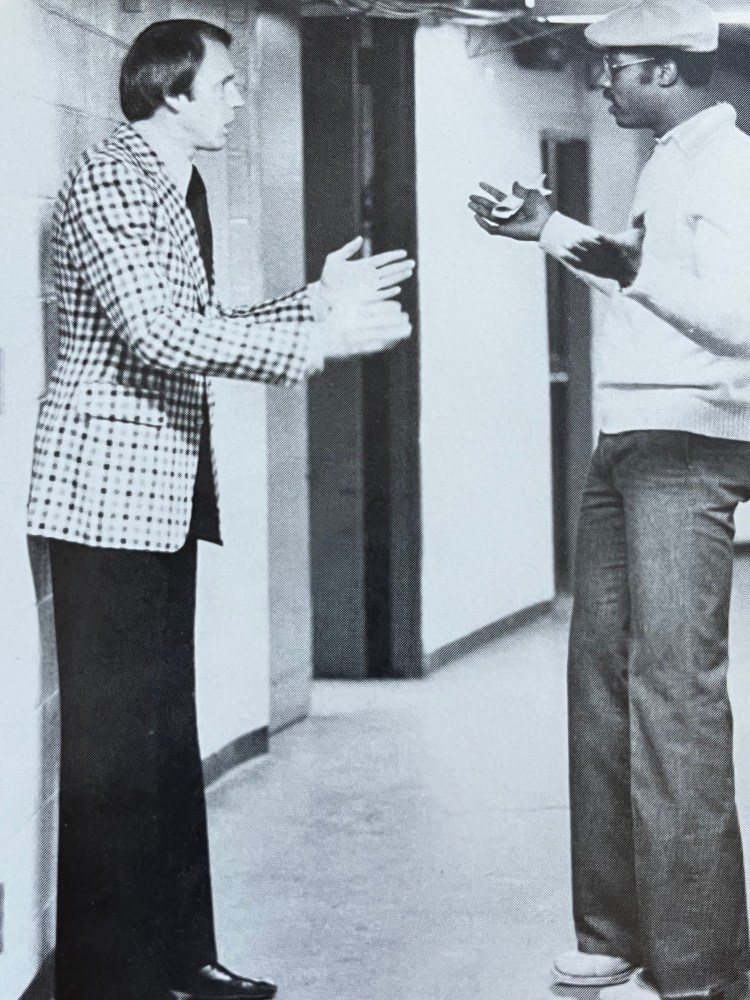

Was having been a player so recently a help or a handicap?

It was a hindrance. I had roomed with some of the players. I was friends with them. I had socialized with some of the guys on that ballclub, because I played with them. And I didn’t try to put up any kind of a wall. What I found was that the players tried to take advantage of me, and I had to put some distance between us. I didn’t want to do it, but that’s the nature of the business. You can’t trade somebody you’re too close to; you can’t cut them. There’s just so many different things that can happen to cause problems as you go along.

How about a specific example?

Okay. George McGinnis [the Sixers’ forward] lived five minutes from here and was good friends with my kids. He’d come over to the house before I started coaching, and we remained friends after I took over. And then I had to make a decision about trading him. Let me see if I can get the year right. I’d say it was 1978, and I traded him for Bobby Jones. From that point till last year, he never said a word to me. It was as if I had betrayed him, which wasn’t true.

And it was a great trade for the team.

A great trade, but it didn’t change my feelings towards the man. It was my job to try and make the 76ers a better basketball team. And the problem was that Julius Erving and George McGinnis did not complement each other. And who was I going to get rid of? McGinnis or Erving? That was an easy decision.

What kinds of things did you do to establish your distance from the players?

First of all, we made several trades. As soon as you start making trades, I think players look at you differently. They don’t feel that secure. They say, “Hey, this guy means business.” All of a sudden, there may be a little more fear. But the most important thing I had to develop was respect. I didn’t care if they liked me as long as they respected me.

Did your youth and physical condition make regaining the players’ respect more difficult?

No. The great thing about coaching is that the first thing you have to do is look in the mirror and evaluate your strengths and weaknesses. As a player, you’re very self-centered, even though you might not realize it. Sure, you want the team to win, but you’re also concerned about being productive yourself. And now all of a sudden, you are the coach, and you have 12 men to blend together. What are your strengths and weaknesses in dealing with people? I’ve always said that it’s a shame you can’t be a coach before you’re a player, because you’d have an entirely different approach to the game. You’d be a much better player. If I’d had to coach me, I’ve often thought, there either would have been some drastic changes to make or I’d have gotten rid of me as a player.

In your early coaching days, did you ever wish you could go out and play for the team?

I never put myself in my players’ position: How would I do this? No, I was able to leave that part behind me. It’s not hard. But that’s one advantage of having been a coach and looking at the game now. You know, some [TV] analysts will say, “Why isn’t the coach playing so-and-so? Why is he doing that?” But I know what he’s thinking; I know what he knows about his players, how each one responds to different situations. For example, a player could be 0 for 15. There’s five seconds left in the ballgame, and still the team runs a play for this guy, because the coach knows that he is a money player. He’s going to respond to the situation by raising his game to another level.

Some nights, a player who could score 40 points a game doesn’t want to see the ball: “Please don’t give it to me.” They’ll find a way to hide right on the floor. Coaches have to know these things about their players.

What was your greatest strength as a coach?

I think it was preparing the team defensively—at playoff [time], especially. And that was very strange, because I always thought of myself as an offensive player. Once you become a coach, you look at the game differently. I began to believe in creating your offense from the defensive end of the court. And, I think the 76ers became a very good defensive ballclub.

I’ve always been a believer in a running team, and in order to run, you’ve got to create turnovers, block shots, or get defensive rebounds. You have to do something defensively in order to run. Especially with the kind of ballclub we had. We did not have what I would call a good set offensive ballclub, which may have been partially my fault. But we didn’t have a Jabbar in the low post, a Byron Scott. People who could really run the plays, guys like Larry Bird. So we had to approach it a little differently, and I had to become a salesman to prove it to the team. Because when I first took over from Gene Shue, they were doing a lot of switching on defense—I thought they were soft defensively as a team. So we changed a lot of things and gave each guy more responsibility in playing his man. Defense became hard work, but after a while, the players saw results, and they started enjoying it.

You speak of coaching very fondly. Do you want to go back to it?

No, I really don’t want to go back. It’s not the games or the people that are the problem. It’s the lifestyle—the 5 A.M. wake-up calls, the traveling, the hotels. I’m not a good sleeper in hotels. I toss and turn, and if I get a couple hours sleep, I’m lucky. But that’s the NBA—one-night stands. The game just takes you over. And even when I was home, I’d be down in the basement here. Over there [pointing to the videotapes], watching movies. I don’t know why I still have them, these old films. But I had boxes more. And I’d sit here and watch films and work. And I’d be home, but I wasn’t home. And my wife and two girls were upstairs, and it’s amazing that they were able to go through all that. It was very selfish of me. After 20 years, it was time for me to move on. But, still, I spent a few months thinking about it. And then—I’ll never forget—it was funny. One day I was upstairs with my wife, and I said to Sondra, “I think it’s time that I retire.” And she said, “Whatever you want to do.” That’s what made it enjoyable, I guess, having a family that was so supportive. But if I’d have coached any longer, I think I would have ended up with a bitter taste in my mouth.

A Change of Venue

Since Billy’s got to go to New York to talk to Dick Stockton, his CBS Sports play-by-play partner, about an upcoming telecast. Since I’ve got to eat, and since he’s got a year-old bar in West Conshohocken, we’re gonna go over to Billy Cunningham’s Court on Front Street to finish our chat. We’ll both drive, because afterwards, Billy will continue on to the 30th Street train, and I’ll head home.

The bar is a pleasant, noisy spot, which looks like a Boathouse Row place outside (with its half-timbers and outline of bulbs) and maybe Billy’s basement crossed with Sam Malone’s “Cheers” set on the inside. There’s lots of carved paneling, a white-tile floor, green-shaded billiard table lamps, and a big center bar. Behind the bar, just like at Sam’s place, there are fresh-faced bartenders in rugby shirts, and pictures of the owner in his glory days. Billy sticks with coffee, and I have Civera Salad, a charbroiled chicken breast on a bed of spinach with a bacon-and-vinaigrette dressing. It’s named for one of Billy’s partners (neighbor Skip Civera; the other partner is Jack McMahon, who was Billy’s assistant on the Sixers). After our philosophical morning (and maybe because I’m drinking Bass ale), we stick to the present (more or less) and talk about specific personalities.

One last set of questions, and I guess you’ve been expecting these. What’s happening with the 76ers? You took them to the top, and now they’re also-rans.

It’s truly a shame. It started with the Ruland-for-Moses trade. Then Ruland went down [with an injury], and everything just collapsed. They didn’t get Brad Daugherty [the University of North Carolina basketball star coveted by the 76ers, but drafted by the Cleveland Cavaliers]. They went for Tim McCormick after the draft to back up Jeff Ruland at center and said, “Let’s get Hinson to go with Barkley and Cliff Robinson. We’ll have a good frontline.”

But it all began when they said, “Moses is over the hill. He’s not going to be able to play here anymore.” From that point on, everything went bad. The Andrew Toney situation. They bring in Gminski and then Coleman. What they have to do now is slow down. They’re making move after move after move. Whoa! Slow down. Julius Erving retired. Bobby Jones retired. Go slowly. Make a move here; make a move there; you don’t have to rush. Build something, and I think that the people in Philadelphia will understand. I don’t know what kind of team they’re trying to build. Are they building through the draft? Are they trying to build a foundation of veterans? There is such a mixture on this team; I don’t know who they are.

Was the Malone trade a good idea?

Looking back now, no. But then, there was no question. There was a little tension between Harold Katz and Moses. Katz was probably a little frustrated paying Moses that kind of money and not getting the world championship back. Maybe Goukas became a little frustrated with him, too. Maybe Matty had a few words with Moses during the course of the season, and they thought it would be a good trade. But Ruland never played.

If Ruland had played . . . ?

It’s so easy for me to sit here and speculate because I’m not there. I wasn’t sitting in on those meetings. I didn’t live with Moses Malone that last year. I don’t think Moses plays at the same level he did when he was 25, but no one does. He’s been playing pro ball since he was 18 years old. But the thing is, he’s been an all-star center every year. There he is, starting on the All-Star team this year, and now look at him. He’s carried the Bullets on his shoulders. So, it’s turned out to be a bad trade.

Has the 76ers’ psychology turned sour?

Cliff Robinson is a good player. Gminski is a good player. Charles Barkley is a great player. They have a nice frontline. But I don’t think they know who they are, because there have been so many changes since training camp. You can’t make all those changes and expect to be productive on the court. It doesn’t happen.

Tell me about Charles Barkley; how has he become the player he is?

He’s changed a lot. The first time I coached Charles was his first year, and he weighed over 280. Now, I guess he’s 255. And he did not have a very good work ethic back then, did not like to run back defensively, did not want to play the whole game. His motto was, “I’ll give you a few minutes here and a few minutes there.” But he’s been able to overcome all that. Now, you might want to criticize him for other things, but he’s going to give you an effort every night.

What about Maurice Cheeks? Is he a saint or what? I’ve never seen anyone put out the way he does.

He’s a special young man, and he always will be to me because he was the first player we ever drafted while I was coaching. Jack McMahon always had a saying for everything. He’d say, “Some players have small sponges to absorb what you’re throwing at them, and others have larger ones—Maurice has a huge sponge.” Whatever you tell him, you only have to tell him that one time. He will absorb it, and he’ll do it. He’s a very quiet, shy young man, but he’s a fierce competitor. He’s got to be really struggling right now, because he doesn’t play for any other reason than winning. Statistics have meant absolutely nothing to him from his rookie year ‘til now.

You mentioned Andrew Toney. What happened to him? Was it a coaching failure? A management failure? Or a physical problem?

I think Andrew Toney is hurting. How severely, I don’t know. I know that Andrew just does not have the highest threshold for pain. But he is hurting, and you never know how badly someone is hurting until the pain’s in yourbody. I remember Bill Walton; people said, “He’s just dogging it. He really doesn’t have these problems. He could play through them.” Well, they had to reconstruct both his feet.

Are there more injuries like Walton’s and Toney’s these days? Do you have an explanation for them?

I think the kids play too much; they’re playing 12 months a year. In college, when their season is over, they’re off to Europe to play on some tour or another. And there’s the same thing going on in the pros. You have your rookie camps, you have your veteran camps, and on and on. I just wonder if the body might not be saying, “Give me a breather; let me rest.” When Andrew Toney signs a seven-year deal for $700,000 a year, I think I would want to know something about his injuries so when the next Andrew Toney comes along, I’ll know whether or not to sign the next seven-year deal.

One last question. You coached Darryl Dawkins and must have heard the sad news about his wife’s suicide. Now I read that he is over 300 pounds and still looking for a team. Why didn’t he develop as a player and a human being?

He was too young when he came into the league, and he came in with the wrong team, then went in the wrong direction. He never had basketball as a number-one priority. A good kid, but never serious. As much as he talked about it, he never wanted to be a star, because that meant responsibility.

Would college have helped him?

Yes. It would have allowed him to grow as a young man instead of throwing him with guys 32 years old with four or five kids to feed. Those guys look at basketball differently: “This is a business. This is work. I want this job. When my basketball career is over and I get out in the world, I’m not going to make six figures. So I’m going to keep this as long as I can.”

Instead, Darryl’s attitude was, “Hey, I’m getting paid to play basketball.” It’s a shame, because he’s a bright young man. I fear for him, for his future. Financially, he’s hurting. I wonder if he’ll ever find peace of mind, find something to do with his life, something he’ll enjoy. I don’t know if he’ll ever find that, and that’s scary.

****

After all that talk about Billy C. as a coach, after all that talk about putting distance between himself and his players, talk that made me (for one) a little uncomfortable, and, finally, after considerable talk of playing and cutting and trading, about guys with low thresholds of pain, and guys who aren’t willing to put out every night the way stars have to, I think there is one corrective we need to insert before we go: Billy Cunningham has certainly grown up in basketball (and in other ways, of course), but, happily, he’s still not a grown-up.

Billy Cunningham today maintains all the enthusiasm for roundball he has ever had, all the obsession with it that, as a kid, kept him going from playground to playground. He’s been a super substitute, a starter in the All-Star game, and one of the most successful coaches in the history of the NBA. He has not put all that much distance between himself and the players he coached, between the suburban businessman he is and the player he once was.

He’s sure that Andrew Toney is feeling pain; he hopes that Darryl Dawkins gets his life back together; he knows that ex-Golden State and Cleveland great Nate Thurmond is out of the hospital, and that Butch Komives (an NBA journeyman and Thurmond’s teammate at Bowling Green State University in Ohio) owns two restaurants and a bar in Toledo, for God’s sake. More importantly, Billy Cunningham knows that Joe Caldwell, a fellow sufferer on the Carolina Cougars, is unhappily working for a travel agent in Arizona and still trying to get what he thinks the ABA owes him.

So, the point here—as we leave Billy Cunningham’s Court (both figuratively and literally)—is that Billy C. keeps in touch with the guys he played with and coached in the NBA. He does it because they’re his fraternity brothers. “The great thing about sports,” he says, “is that you get to know each other. Black, white, green, whatever color you are, you live together. You understand the other guy’s problems, and you have a better feeling for him. It’s a shame that everybody can’t go through the experience of playing sports together.”