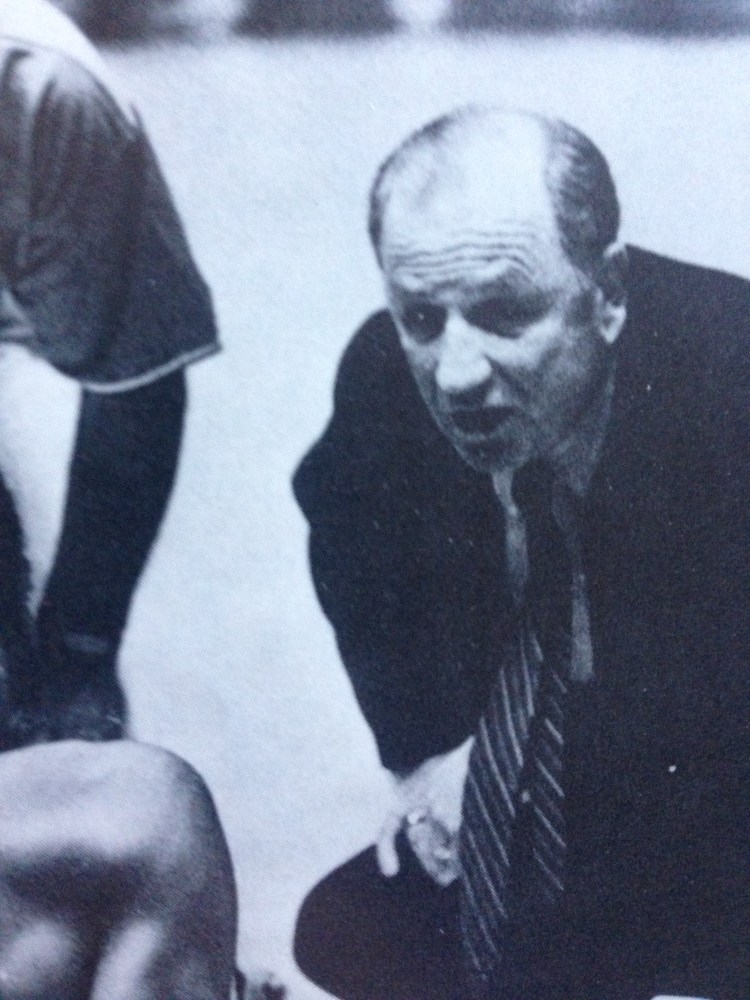

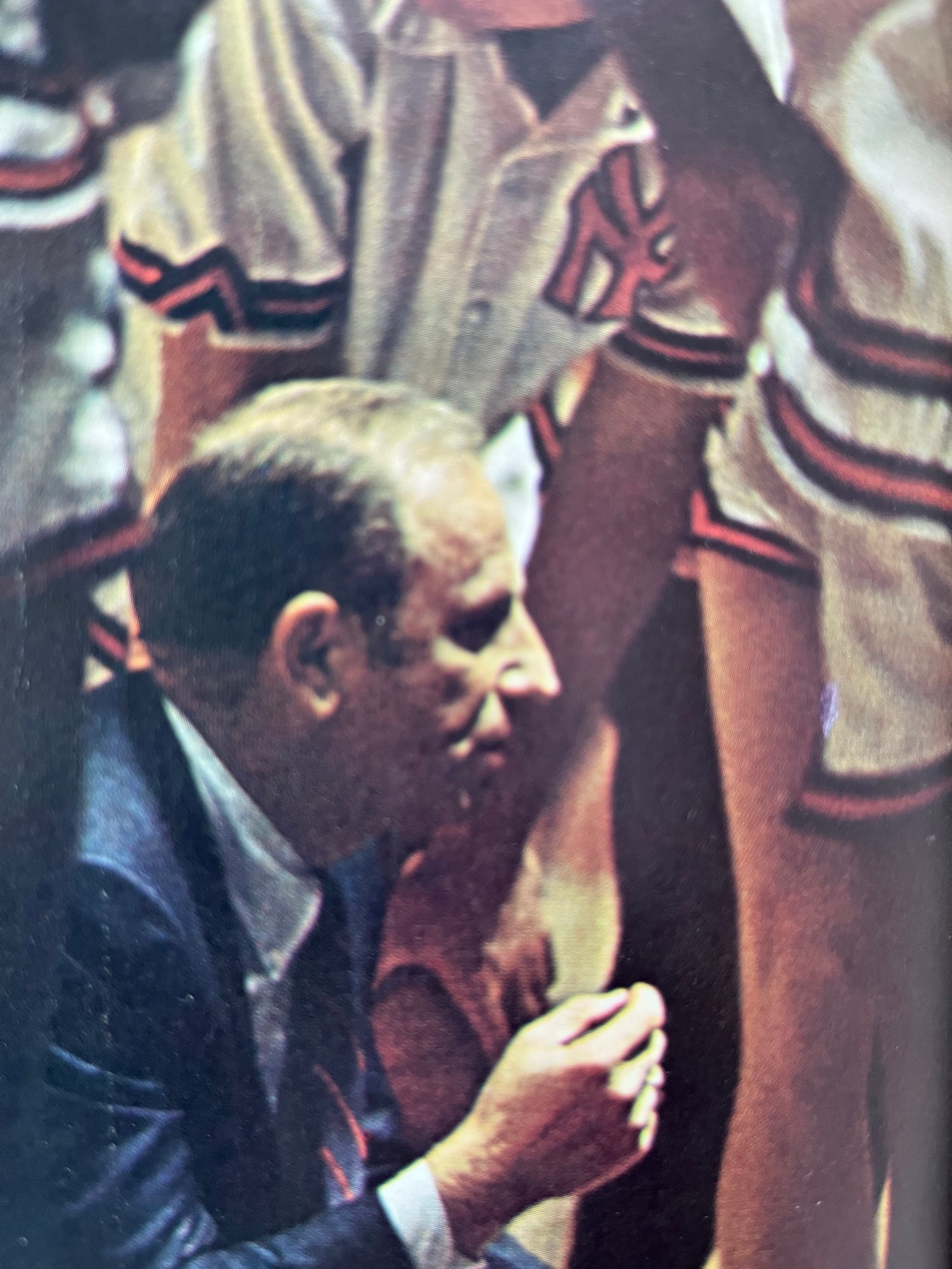

[Red Holzman, the legendary Knicks coach (1967-82) who is now nearly three decades in his grave, remains sports royalty in his native New York. Deservedly so. He remains a proud product of the 1930s New York schoolyards who taught the game the right way and guided the Knicks to their only NBA championships in the franchise’s storied history (1970, 1973).

Holzman was also just a simple man, a tinkerer set in his middle-aged ways and a reluctant NBA signal-caller with few delusions of taking the league by storm. That’s the synopsis of ace sportswriter Dave Klein of the Newark (NJ) Star-Ledger. Klein’s excellent profile of Holzman, published in the January 1970 issue of the magazine New York Jock and transcribed below, is one that deserves to stand the test of time. Give it a read. Tell me what you think.]

****

The first reaction is outrage. Just who is he kidding?

No one can be that simple, this easily happy, this totally pleased with his lot. No one never complains. No one takes all the people around him for exactly what they are and then finds a part of what they are that he can like. No one looks forward to road games because when they are finished, he can take his friends and find a restaurant that will serve steak, radishes, scallions, and well-done French fries after midnight.

But this is Red Holzman. And it takes a while to realize that he is putting no one on. For a long time, before the truth burst through, interviewing this man is not pleasant. You feel—no, you know—that he is hesitant and reticent because you are not a part of his daily world, a very tight little world, because you are an outsider. Or else he’s acting this way for the pure perverse pleasure of it. But then you talk to those who know him best, his players and the reporters and Danny Whelan, the trainer, and the publicity man, and they say Red is always this way. He takes to people right away, always, but on his terms. This is Red.

Well, this, too, is Red. He wants certain things. He wants friends, and he wants race tracks. He’s genuinely pleased that the NBA thought to plant franchises near Santa Anita and Laurel and Pimlico. He wants those miniatures of Chivas you get on airplanes, and he wants a glass filled with extra ice whenever he is drinking. He wants his six months of privacy, so we can go to the beach on Long Island and watch TV and be with Selma. And if you can get all this, he figures he can put up with what he considers to be at once the best and the worst job in all the world—coaching the New York Knicks.

Which, incidentally, brings up a point. Do not, at least not in Red’s company, refer to his team as the Knickerbockers. He visibly shudders at this term, one obviously meant for use only by the Madison Square Garden corporate accounts. “Knock off the Bockers,” he grins. “Keep it simple.”

Simple. Red Holzman is simple. Delightfully, marvelously simple. He is a 50-year-old square. He is too plain, and too easy to like. He even carries a pocket watch, a genuine old-fashioned one with the big numbers and the white face and the heavy, notched whatever-it-is that winds it. Why can’t he be loud, like Auerbach, or quietly nasty, like Ramsay, or bubbly, like van Breda Kolff? Why must he be exactly the way he comes on, low-key and square? No one is. It is most distressing.

And there is also this about Red Holzman. Like any normal, reasonably, intelligent, properly, motivated Jewish kid from Brooklyn, his big dream was to win Macy’s in a gin rummy game and convert it into the biggest basketball court-delicatessen in the world. That, however, somehow managed to fall through, so Red went to work.

He says he settled for what he wanted to do. (Did you?) First he played basketball, a few NIT and All-America years at CCNY (he is a member of City College’s Hall of Fame), then 10 years with the Rochester Royals. Then he coached with the Milwaukee-St. Louis Hawks. Then he became the Knicks’ chief scout in 1958.

Finally, on December 27, 1967, Red replaced Dick McGuire as coach. Dick McGuire replaced Red as head scout. Red was jealous.

“I did not want this job when they offered it to me,” he says. “But they told me they wanted me to have it, and when you work for people eight years, and when they tell you they would like you to do something, what else can you do? You do it, right? Of course you do.”

So Red Holzman, the plainest man you ever met, and for that reason perhaps the most complex to probe, thinks of himself as an ordinary coach blessed with great good fortune and extraordinary players. And it does not insult him to say his basketball theory has not been altered since the days of choose-up in the playground of P.S. 178. “Maybe not,” he says, “but there is sure one hell of a difference in the talent, right?”

Red Holzman, who coaches what is the very best team in pro basketball today, a team with every necessary ingredient for greatness, approaches this job with a conceptual strategy astounding in its utter simplicity. In this day of scientific everything, he calls it teamwork.

“You give me five guys, not one of them a superstar. If they are willing to play together, and if they do it right, and if they believe in themselves and each other and in the principle of it, you can build them into a championship club. They can be a better team than the one with the supermen, because they do it together. It’s like putting your five against just one or two of them at any given moment on the court. You come out ahead. You’ll win. It works.”

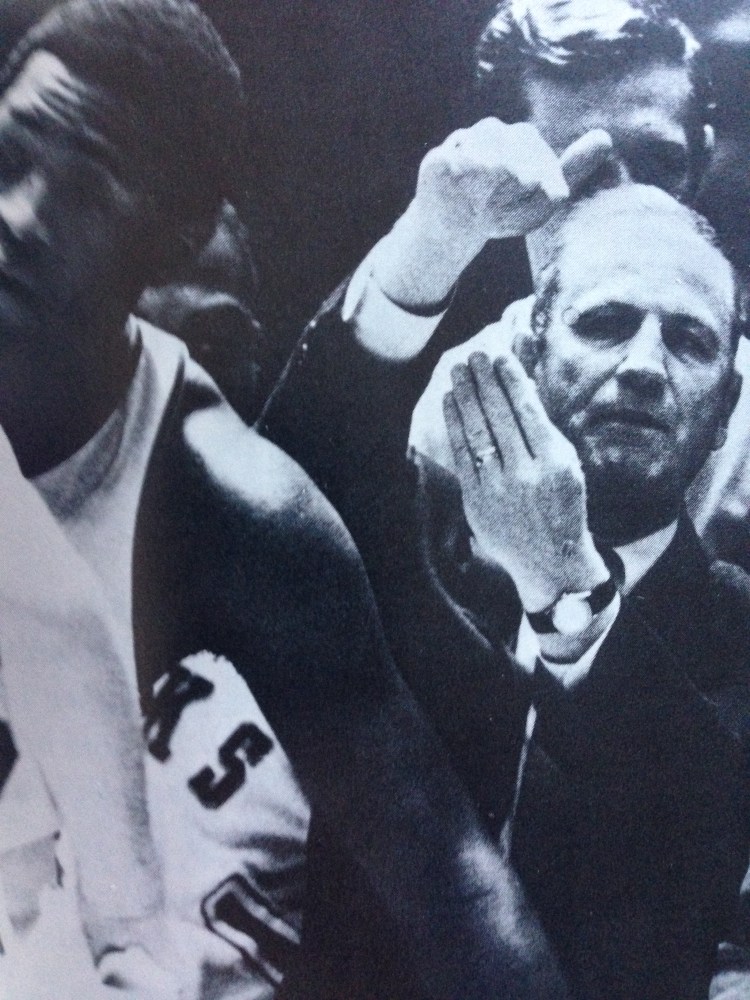

With Red Holzman’s Knicks—and they are, indeed, his, an extension of his well-ordered psyche—it all begins with the defense. The Swarm. The Octopus. The Defense-Offense. The Defense That Ate the NBA. “Baloney,” Red snarls, “those are writers’ words. Just call it team defense.”

Why not? Red’s team defense, then, works this way: He takes Walt Frazier and Dick Barnett, the guards, and he puts them up front to force. They must channel the ball to the sidelines. It is the first part of the trap. And they do it with quickness and aplomb and colossal nerve. Frazier does it because he is a very special one; Barnett does it because he is smart enough to see that it works.

Frazier and Barnett. The heart of this defense. Instead of three-quartering their men, they front them. They play facing the ball, backs to their men, eyes on the ball, while Holzman yells, “See it, see it, see it” from the sideline. Frazier with the quick hands, so quick it is almost disturbing, is there to gamble on the pass. He is there to make the steal, to break the game, which he does anywhere from six to 12 times a night. And then he goes bounding downcourt, cocky even then, dribbling with a swagger, and if they are home, the Garden rocks and shakes with the thunder of the captivated, wild-eyed crowd.

But it is more than the guards. Indeed, it has to be more if it is to work. It is the two forwards, too. Dave DeBusschere and Bill Bradley.

DeBusschere came to New York last year from Detroit, and it has been the smartest move Red Holzman and his advisor, general manager Eddie Donovan, ever made. Dave supplied the final need, for with his experience and intelligence he makes it work. He, too, is necessary as a thief. He will get half a dozen passes a night by falling back into the lane, the middle, when the guard being tormented by Frazier tries to cop out with a high pass diagonally across court underneath the basket. It is what the Knicks want the guard to do; they will destroy him the moment he does it. The moment he does it, he has succumbed.

DeBusschere and Bradley. Bradley, who is pure pro now and who Cazzie Russell couldn’t move out with a dictionary because Cazzie doesn’t like defense. DeBusschere and Dollar Bill. They are the drop men. They must cover their men, of course, but they guard only “half a man” each. They also watch the ball, and when the guard gets that frantic, maddened, look on his face, they smile at him sweetly, fall back and dare him to loft the pass. They cover their men, sure, but they cover the ball, too, wherever it is. They trap and they switch off and they adjust for picks, but they do it all with one eye on their men, one eye on each other, one eye on the ball, and one eye on that 24-second clock. Four eyes? Victims have sworn they have at least 10.

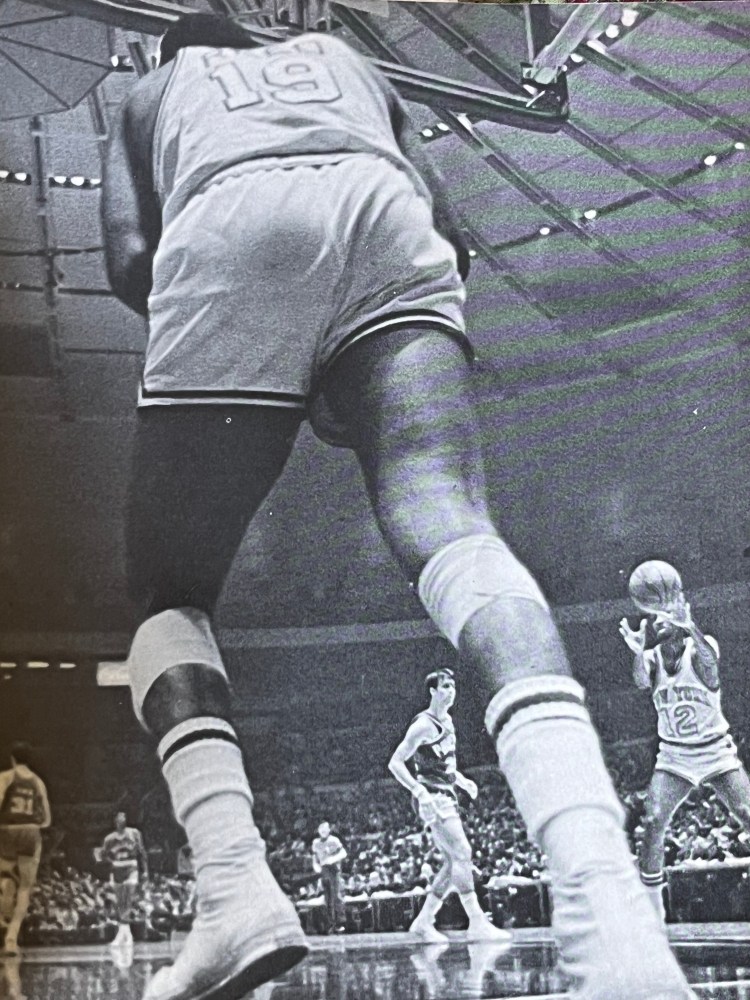

Then, and because the defense is so designed, it all falls to Willis Reed, the center, the team captain, to anchor this devastation. There are, perhaps, better rebounders in this league, men like Wilt and Thurmond and maybe Alcindor. Perhaps there are faster men, but Reed never trudges upcourt three baskets behind the rest. And there is no one, especially now that Bill Russell has gone Hollywood or something, who plays defense any better than Willis Reed. Not any center alive.

“Willis is all by himself,” Holzman says. “For what he does, for what he can do for this team, I wouldn’t want any other man. Wilt and Thurmond and the kid [he means Alcindor] cannot possibly do more for me than Willis does. They might do less. Willis is a team player, and that is not taken lightly in our system.”

What Reed does, specifically, is intimidate the middle. When Bradley and DeBusschere are cheating off their men to make profit of what Frazier and Barnett are doing, they need a backup. A saver. They need Willis, in case that ball does get through.

They need him to take their men if they get burned on a pick, if they have gambled and been left flat. He takes their man, he switches to the one with the ball, so that Bradley can race in for the rebound. And he can play defense like a cat, sliding around picks, knowing when to hand off responsibility. Knowing when to take it, too. He can cover the forwards because he is quick. Quicker than most men who are 6’10” and weigh 245 pounds. Think about that.

“And they cannot sucker Willis,” Holzman says proudly. “They cannot use their own center to screen him out.”

And the five of them, Clyde and Dollar, Dave and Willis and Barnett, they work it to perfection, driving some men to distraction and others to adulation. “I have never seen a defense like this one,” says Joe Lapchick, who surely has seen all else in the game. “It works so well, and it is so beautifully done. These kids have all they need to become a dynasty.”

Dynasty . . . championship. Strange-sounding words, indeed, for our Knicks. Where have all the lovable nobodies gone? How have fled the days of Phil Jordan and Whitey Bell. A man still remembers when Darrell Imhoff carried his duffel bag backwards, so no one word read “N.Y. Knicks” on the side. They are gone, and good riddance. How quickly one learns to be a winner.

“All these players fit like pieces to a puzzle,” Red offers, high over the Midwest and on a late-night flight to Detroit. “Maybe they wouldn’t all be superstars, but they work well together. I am fortunate to have them, and to have Donovan. It’s his defense, really. I just teach it, but he conceived it when he coached at St. Bonaventure. I’m getting too much credit. I’m not a great coach. Donovan is . . . and Jack Ramsay. I just do a job of work.”

The stewardess saunters down the aisle now and presents the coach with his pre-wrapped, too-cold “flight snack.” It was salami on a roll, and on the roll there was butter. Red groaned, a stricken look on his face. “Butter? On salami? They must be crazy. What the hell, I’m hungry.”

And between bites and sips of Chivas, Red talked about his team and his life. “It’s hard work. It’s repetition, really, no more than that. When I was asked to take this job, it did not make me happy. I liked scouting. It was easy, no pressure. I thought someone else should do it. They thought I should do it. I was wrong.

“It’s the defense, you know. All the success, it’s the defense. It can work like an offense if it’s right. It makes points. It’s a lot of teaching, and sometimes they don’t like me because it’s long hours. The players have to be the right ones, and they have to commit themselves. There’s no changing in mid-season. We are stuck with whatever we have here.”

So is the league stuck with it. “Coaching is based on memory, “Holzman continues. “If you see something that works, take it. Keep it. Someday, use it. Do I feel guilty about borrowing from another coach? Hell, no. I’d be letting my team down if I didn’t use an idea I thought would work. There’s no pride there. I mean it. There are damn few innovators coaching today. We all borrow. How different can you be, anyway? We’ve all seen it before.”

Through it all, as is subconsciously shunning the glare of attention, Holzman downgrades his role, his importance. “Selma could coach this team,” he says. “It’s that easy. The guys make it work. The bench is good, kids like Riordan and Cazzie and Stallworth, and I have grown to depend on it, but the five who start make it happen.

“I feel sorry for the kids who want to play but sit. I understand. But I am not getting paid to make people happy. I am getting paid to win. I can’t worry about who’s happy and who’s not. People still ask me if I had trouble dealing with Bradley. You know, all the money and Princeton and the Rhodes scholarship and all. Isn’t he different, they ask. I laugh. What’s to be different? He’s a basketball player, isn’t he? What’s different? So he’s smart. So what?”

The plane landed easily, and the team went to bed. The next day they sat around the lobby and decided how to bury the Pistons. And that night they buried the Pistons. They absolutely devastated them.

And after, when Red had finished hurling wonderfully descriptive expletives at the officials, when he had talked to the reporters who cluster in ever-increasing numbers these days, he went to Russell’s near the Cadillac Hotel with a few friends. Russell’s is a late-night steak place.

For a while, he talked about the game. How about Bellamy? He switched pivot feet, and the officials never saw it. Didn’t Frazier look good? God, he’s quick. DeBusschere got his eye back, didn’t he?” And then, nearly imperceptibly, Red slipped back into his private posture.

“You never listen,” chided Frankie Blauschild, the publicity man. “When you wanted to bet before, I told you the six. I told you. But did you listen? No, you did not listen. You bet the four. What happened? Tell the man what happened?”

“The three won it, coach.”

“Don’t be smart, Frankie. You never listen. That’s your trouble. Now where is the waitress? My ice cubes are melting, and I need salt for the radishes. And another drink. Frankie, tell her to listen.”

It is Red Holzman’s world, and if you care to talk the game or eat radishes, you are most welcome in it.

This one is great! It tells about how great a man Red Holzman was,and analyzed the Knicks’ defense!

Thanks a lot for your find and upload!

LikeLike