[Several years ago, I interviewed an obscure former college basketball coach. He’d been an assistant during the mid-1960s in the Big 10, where he burned out on the college game and its politics and eventually moved to Florida to chase a business career. He’s been there ever since. As our interview wound down, I asked him if he still talks with any of his old coaching buddies? He said no, then added with a chuckle, “But I was on the beach the other day, and I saw this old guy coming out of the water in a wet suit like the ancient Mariner. You know who it was? Jack Ramsay.”

That would be the former college and NBA coaching great. Ramsay had settled in Florida and, when not doing the commentary on the NBA’s weekly radio game of the week, still trained like a 30-year-old ready to conquer his next triathlon.

This article, from the December 1988 issue of the magazine Philly Sport, profiles Ramsay, his amazing coaching career, and his pursuit of extreme physical fitness in his 60s. The article comes from B.G. Kelley, who then described himself as “a starting guard for the Temple Owls in the mid-60s,” and who “once dribbled through Ramsay’s legendary zone traps and lived to tell the tale.” We’re glad he did. Kelley went on to publish some great stuff in other magazines and, the last I checked, teaches writing at the International Christian High School in Philadelphia. One final note. Between the months-long process of editing and publishing Kelley’s story in Philly Sports Ramsay would step down at age 63 as head coach of the Indiana Pacers, ending his 20-plus year run as an NBA head coach.]

****

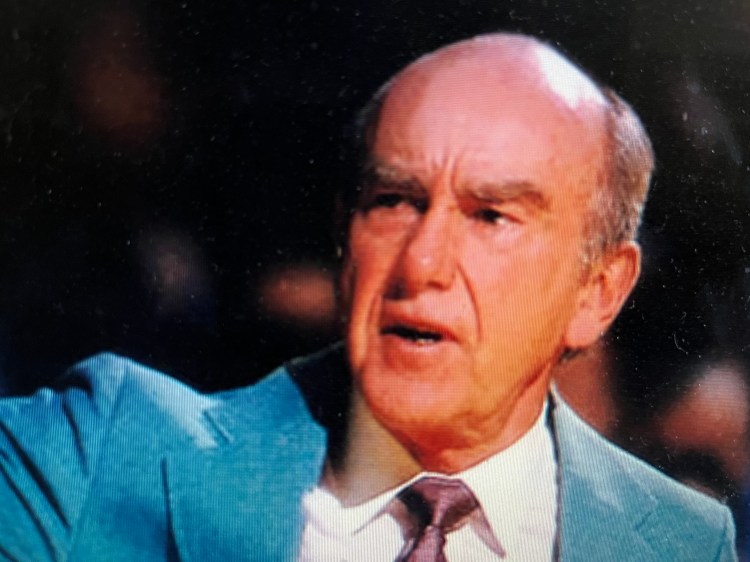

It is 7:30 A.M. Indianapolis is sleepy, like an untilled cornfield. Jack Ramsay, decked out in blue sweats and blue running shoes, drives up to the front door of the Hilton Hotel in a snappy red Camaro. I recognize him immediately. Ramsay is still the man indelibly imprinted in my memory from that time, nearly 25 years ago, when he was coaching at St. Joe’s, the tiny Jesuit-run college on City Line, and I was the tiny 5’8” Temple guard praying for the strength of a spinach-gorged Popeye to pass safely through his plethora of pressure defenses.

Today, Jack Ramsay’s team is the Indiana Pacers. But he is still the same man. Only older. And more fit. You could strike a match against his lean, mean 6’1”, 170-pound body. “Good to see you again,” he says. I jump in. We peel out. The city is left behind.

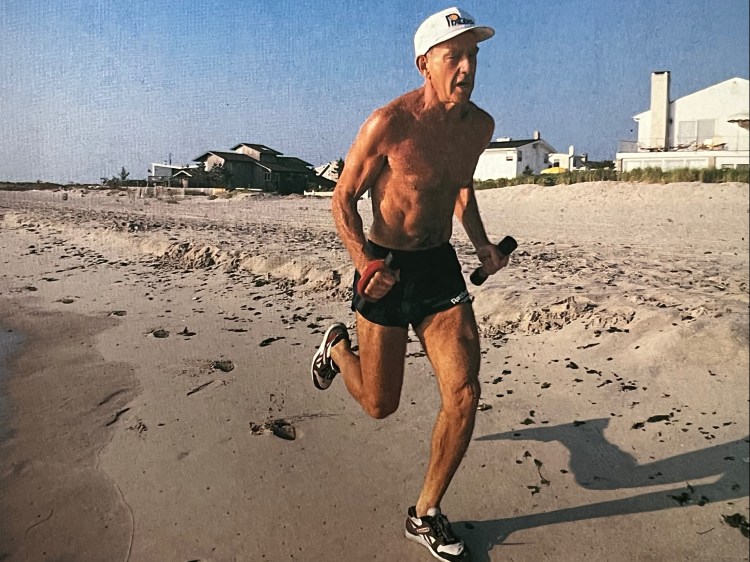

“The Challenge” is set for 9:30—the “Jack Ramsay 10K Challenge,” a footrace through the rolling Indiana countryside. Ramsay is forever cutting to some chase in his life. He doesn’t care much for slick. He cares even less for soft. He wants nuance and texture over quick hits. That’s why he’s chasing high-grade physical fitness. “Another step to another level of living,” he explains. On this brisk mid-April morning, Ramsay is running 6.2 miles. The man, for Pete’s sake, is 63 years old.

Running has become Jack Ramsay’s relaxation. “It gives me time,” he says, “to sort things out in my personal life, to reduce the anger and frustration over a tough loss. The pro game can weigh heavy on your mind. Every game is a battle for us, because the Pacers don’t have the gifted players other teams do.”

There is no anger, no frustration this day. The Challenge is Ramsay’s idea of something to do for charity in Indianapolis. The proceeds will go to the Riley Hospital for Children. It is also part of Ramsay’s preparation for a series of seven triathlons he is planning to enter over the next few months. “Ever do one?” he asks. “It’s the ultimate competition.”

Competition—with others or himself—has always been the one thing capable of reaching up, like fiery tendrils, from Ramsay’s innards and taking charge of his mind, his body, indeed, his soul. This inner feral heat has not cooled in Ramsay, in spite of that siege that age lays on even the heartiest of mortals.

Philadelphia 76ers head coach Jimmy Lynam, who played for and has coached with and against Ramsay, remembers his first encounter with that fierce persona. “It was 1959,” he recalls. “I was a freshman at St. Joe’s. After practice, some of us would get up halfcourt games. He wanted in on them. He was about 34 then, but let me tell you, he could mix it up real good. He wasn’t out there to coach, believe me. And he wasn’t out there to lose.”

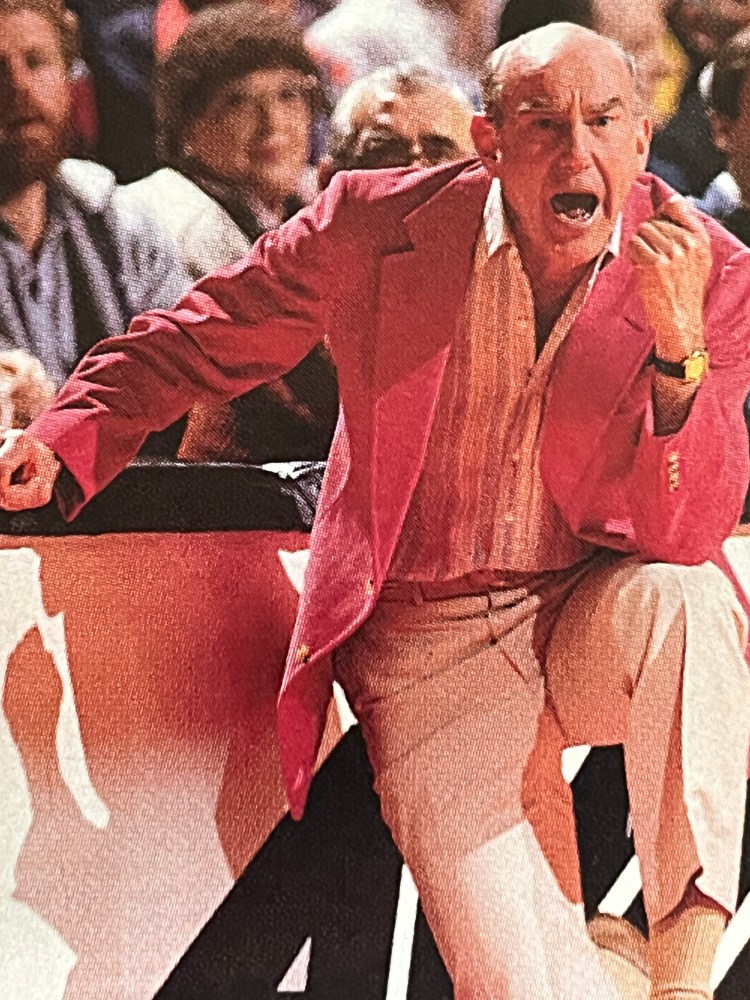

There’s still no quit in him. And a chalkboard session before one crucial game last season against the Sixers—a game both teams needed badly to win to keep alive playoff hopes—Ramsay was palpably edgy, painfully precise. “We need to double up on Barkley aggressively—aggressively— then rotate aggressively,” he stressed. “It only works if you do it aggressively, give your man a hard piece, okay, a hard piece.”

That night the young Pacers attacked Barkley and the ball like loose pit bulls. Barkley posted up under the basket. He took an entry pass from Maurice Cheeks. Quick as a couple of bull bites, two Pacers doubled up—aggressively. Barkley had to kick it back out. The Sixers’ guard swung the ball to Albert King. Yet another Pacer bellied up on King and gave him a hard piece. It went that way all night. The Sixers were forced to take bad shots or no shots. The Pacers walked off with a 126-92 win.

****

Race headquarters for the 10K Challenge is the Park-Tudor School. An hour before the start, men in their mid-20s with clean-as-cornfields looks, clean-as-glass lines cut to their muscles, and heartland-grown girls, Miss America nubiles with tight bodies, stop by to pick up their race numbers. Ramsay glances at them.

“I was always interested in fitness,” he says. “Maybe not to the extent I am now, but I played basketball well into my 30s, took up serious tennis after that and always did some biking and swimming. I didn’t do too much running until I decided to get into triathloning. I had an Achilles tendon problem, as well as torn ligaments in my ankle, so I didn’t think my legs could take the pounding. Funny, though, the more I ran, the better my legs felt.” He glances again at the mid-American cuties and beauties. “Let’s go.”

He heads outside. The sky is as blue as sapphire, the clouds as soft as cotton. Ramsay smiles. For good reason. There are close to 2,000 runners waiting for the 9:30 gun. At eight bucks an entry, it translates into a lot of dough for the hospital. “Terrific,” he crows. “Terrific.”

Ramsay has always kept his ego in check. “I’m not a seeker,” he says. Yet even though he shies away from the spotlight, the same way an agoraphobic does crowds, his record speaks for itself. “Oh, no doubt about it,” says Lynam. “He’s up there with Red Auerbach, Bobby Knight, anyone who ever coached this game. He’s put down the two things that make you special: innovation and success. He popularized trap defenses and brought motion offense into style. And he’s a winner.”

Indeed, Ramsay hung up a 234-72 record in 11 years at St. Joe’s, with 10 postseason appearances in the NCAAs or NITs. In his 20 years as an NBA coach, which includes a 1977 NBA championship with the Portland Trail Blazers over the Sixers, he has posted 864 victories, second only to Auerbach’s 938. If he chooses to stay in the pro game for another two years, Ramsay could pass the legendary Boston Celtics genius as the winningest coach in NBA history. “I’m not caught up in numbers,” he says. “I just hate losing.”

Ramsay strips off his sweats. He is ready to run. It is his icy, ebony eyes—intense, focused—that make it clear he will not be saved by someone else’s idea of who he should be.

Ramsay grew up in a strong, disciplined, authoritative Catholic family. His father, a mortgage and loan officer, took nothing for granted. Neither does he. Ramsay doesn’t ask for anything free, doesn’t give anything for free. A Philly kid, he graduated from Upper Darby High in 1942, then enrolled at St. Joe’s. After his freshman year, he entered the Navy.

In 1946, he returned to the Jesuit-run school. Ramsay claims the Navy experience, where he had volunteered for underwater demolition duty, brought him back mentally tougher—so tough, at times, it seems like his mind can jackhammer through a mountain of rock and come out unchipped.

Known as a hustling, cerebral, take-no-prisoners player, Ramsay spent three years on the Hawk varsity. His best season came as a junior, when he averaged 11.3 points a game. After graduating, he played weekends in the rugby-rough old Eastern League for $40 game. During the week, he taught and coached at St. James High in Chester. In his spare time, he went after a Ph.D. in education at Penn. He always believed—still does—that the less you do, the lazier you get.

Jack Ramsay has run his life in the same style the Pope runs the Catholic Church. He doesn’t trust outsiders, and he doesn’t like interference. “He’s loyal to the people who have proven their loyalty,” says Jimmy Lynam. “He’s the same guy today as he was 25 years ago, and that is a great strength.”

****

Crack. The footrace is off. Ramsay looks good out of the gate. He puts down a sloping, sliding gait, like someone stamping out a string of cigarette butts. In the early going, he is in the pack up front. But there are hills—long, rolling hills—and they rake out their measure. Ramsay falls off his early pace. “I haven’t put in the quality kind of training I would have liked because of a slightly pulled groin muscle,” he had said earlier.

Running with Ramsay births a thought: He is not his generation’s reflection—friends sharing a park bench or a beer, theories of aging and dying. Ramsay is the oldest guy in the race. What is he trying to prove at age 63?Ramsay says, “Age is relative. Some people are old at 20, some young at 60. It’s how you approach aging mentally. I don’t think in terms of numbers, just in terms of taking care of my body, to be as active as long, as hard as I can. If I keep my mental and physical energy high, I’m not trying to prove anything, just be as fit as I can.”

Reggie Miller, one of the Pacers’ young guards with a downtown shooting stroke, says, “I look at the coach as being around 40. He has the mentality and energy of a young guy.”

So, Ramsay runs and swims and bikes and pumps iron to rev up his energy quotient. Yet, a lot of that energy comes hard on the side of rawness and aggressiveness in the rage for perfection. Sometimes it tears him up. In 1966, it tore him up good. He was forced to leave coaching because the flame of perfection burned out of control. “I was having trouble with my vision,” he says, “and it was related to the stress of winning. Basketball and winning were everything, all my life.”

Ramsay had developed an edema—a fluid sac on the retina of the right eye. “All I could see was light around the edges.” Was there a possibility of getting it in the other eye? “Oh, yes.” When the opportunity came in the summer of 1966 to become the general manager of the 76ers, Ramsay left St. Joe’s. “It wasn’t that I was looking to leave,” he says, “but I thought, well, this is what I should do for my health.” With medication and treatment, the problem cleared up in three months.

Ramsay spent six years with the Sixers, two as general manager and four as head coach. As GM in 1967, he put together a championship team that ended the Boston Celtics’ run of eight consecutive NBA titles. In 1968, he took over as head coach and guided the Sixers into the playoffs three straight years. After a dismal 30-52 season, Ramsay moved on to coach the Buffalo Braves.

Evidently, what we see of him today on TV—storming away at refs, his Irish mug flushed like a traffic light; or in more controlled moments, his arms folded tight to his body like wrought iron, rhythmically chewing gum and freezing a faltering Pacer with those gelid brown eyes—belies the conscious effort he has made to smother his rage over losing. “I’ve been trying,” he admits, grudgingly, “to make a change in my life by accepting things as they are, not make winning a life-and-death situation.”

Once, Ramsay was demonically possessed. Whether it was against Villanova and Wally Jones or Wichita State and Dave Stallworth when he was at St. Joe’s, or against the Boston Celtics and Larry Bird or the Los Angeles Lakers and Magic Johnson in the pros, winning big games stood at the core of his psyche. When the game was over, when there were more points on his side of the scoreboard than the other guy’s, there was not a damn thing more he wanted—or would ask for.

When he lost, there were long, lonely, walks in back alleys, three dark ghetto streets, sometimes weeping. It was as if he was deliberately begging someone—anyone—to beat those damn demons off the fine line in his mind.

Now Ramsay has chosen to run or swim or bike to blow off bitter defeats. “It doesn’t,” he admits, “get rid of the anger, the frustration entirely, but it has helped to prevent my life from becoming emotionally devastating.”

****

At the four-mile mark, Ramsay powers up the energy of a young man. His arms pump hard through the slants of sunshine. His small, efficient strides are like Haiku lines, relaxed but driving at the same time. He picks up the pace. The 15 years of rigorous conditioning kick in.

Invariably, too much is made of the rumor that Jack Ramsay is in better shape than the athletes he coaches. “Let’s put it this way,” he says diplomatically. “I can’t do what they do on the court, and they can’t do what I do in the pool, on the bike, or on the roads.” Still, there is this nagging sensation that if the Pacers’ players had been as committed to excellence as their coach, they might not have failed to make the NBA playoffs last spring.

Ramsay silently seethed, looking in from the outside. One day last April, as he emerged from a practice session looking hollowed out. It had come down to this: The Pacers had to win four of the five remaining games to get in. “I would like to think,” Ramsay said that day, “that I can train my players so it wouldn’t have to come down to the last week.” The Pacers won only three of those games.

Ramsay passed mile five. The sheer passion of the challenge—to pass as many runners as he can in the stretch—quickens his breath. He cuts hard to the chase. He passes a cluster immediately in front of him, then overtakes a pack of fading runners. Finally, he claps his sights on a couple of gray-haired harriers an eighth of a mile in the distance. Ramsay raises his pace another notch.

With about two-tenths of a mile left, Ramsay closes hard. He kicks it out one last time, his breath hissing—pfftt, pfftt, pfftt—like an aerosol can. At the tape he passes them. “That was my goal,” he says after the race, “to catch those gray-haired fellas in the backstretch.” Ramsay finishes in 48 minutes, 3 seconds, just under eight-minute miles. “That,” he says, “was the time I had set for myself.”

****

Ramsay’s face is like a benediction after the race. We are back at his home in Indianapolis—a cream-colored, Hollywood-like townhouse in a cul-de-sac. It is modestly appointed, mostly in white. The TV is going. A basketball game. Ramsay’s six-month-old granddaughter, Sofia, steals his attention immediately. “Isn’t she something, yes, you are something,” he dotes. “Hi, Chris; hi, Rags,” he yells to his son and daughter-in-law, who are temporarily staying with him.

“How’d you do, Dad?” Chris, a local TV producer, asks.

“Good,” Ramsay replies. “About 48 minutes.”

Ramsay disappears momentarily to wash up and change. Ramsay’s wife, Jean, is in Ocean City, N.J., getting their summer home ready. Ramsay returns—the sacral glow on his face now gone as if rinsed away by water. He appears pallid, sucked thin in the cheeks. “Rags,” he says, “is there any more of that great chicken-and-rice dish you cooked up last night? Rags nods.

Along with his commitment to physical fitness, Ramsay also has made a pledge to nutritional prudence. For the last 15 years, he has not touched red meat, eggs, or fried foods. “Fish, chicken, pasta, fruit,” he says. He fires up the oven. “I’ve always been somewhat of an amateur cook. Not gourmet, mind you. Basic stuff.”

As he replenishes himself on Rags’ spicy chicken-and-rice, Ramsay gets back to basic stuff: basketball. Among those who know him best, The Game is cited again and again as his eternal imprint.

Basketball to Ramsay is more than just 10 players, running up and down the court, and then tallying the sheet afterwards. It is an artistic experience: the rhythmical unfolding . . . the stunning quickness of motion . . . the beauty of the flow . . . the surreal stamina . . . the bonding of five as one, passing, shooting, rebounding, defending—winning. The Game transports Ramsay to a mysterious center of infinity. “Basketball,” he says, “is art, and the creator of that art is the coach.”

Jimmy Lynam knows. “Playing for him,” says the Sixers’ coach, “was among the most pleasant times in my life. Sure, he’s all about winning, but he made the experience more than that. He made the game what it should be—five guys in flow, in blend. And the way he did that consistently was by going after kids who would fit his system, his way of thinking.”

Lynam was one of those kids. It was in the winter of 1959, and, well, let the Lilliputian coach tell the story: “Someone told him that he would like this guard at West Catholic. So he came to one of our games. He sat there for most of the game thinking our other guard, Herb Magee, was me. Finally, someone told him who I was.”

If one basketball concept epitomizes Jack Ramsay’s coaching character, it is pressure basketball. It happened by chance. In 1954, when he was a 29-year-old high school coach at St. James High in Chester, Ramsay put in a phone call to a fellow named Woody Ludwig. It reshaped Ramsay’s place in history.

“I thought it would be a good idea,” Ramsay recalls, “for my kids to scrimmage a college team.” Ludwig was the coach of the nearby Pennsylvania Military College—PMC. Ludwig took the call. “We’d like to scrimmage you,” Ramsay said to him. Confused, Ludwig replied, “Our freshman coach isn’t here right now, but I’ll give him your message.” Ramsay corrected Ludwig. “You don’t understand, I want to scrimmage the varsity. Ludwig chuckled. “Okay, okay,” he said, “bring your kids over.”

Ramsay loaded his kids into a school bus and traveled to PMC. He didn’t expect to get what he got: a good, old-fashioned ass whippin’. “They trapped us the whole scrimmage,” Ramsay says, “and we never got the ball over the halfcourt.”

Ramsay took the idea of pressure defense into his own mind, and it exploded there. “I began to use traps at St. James right after that scrimmage, and when I got to St. Joe’s in 1955, I refined them.” In 1963, he authored a book, Pressure Basketball. It made the New York Times best-seller list.

Actually, the Ramsay miracle-making legend may have begun on February 26, 1958. With six minutes left in a game against La Salle, his team trailed by 16 points. Ramsay called time out and in that always-in-control manner, gathered his players around him and mapped out the zone traps he wanted. Joe Spratt, Bobby McNeill, and the rest of those Hawk Hill bandits—kids with a kamikaze outlook and an inexorable will to believe in the coach’s Impossible Dream—converged on the ball all over the Palestra court, stealing passes, forcing turnovers, and finally tying the game at the buzzer on two McNeill free throws. In overtime, the Hawks dealt the Explorers a mind-blowing 82-77 defeat.

“Ramsay would get kids to go out there and step beyond their abilities,” says Jimmy Lynam, the hub of the Hawk teams of 1960-63.

Ramsay’s impact on Hawk Hill can be seen in the number of players who followed in his footsteps like disciples. At one time, there were 37 ex-Ramsay players coaching somewhere—high school, college, or the pros. Jack McKinney, Paul Westhead, Matty Goukas, and Lynam followed him into the NBA. “I just tried to set an example,” says Ramsay. “How they lived their lives was up to them.”

More than any of his teams, the 1964-65 and 1965-66 St. Joe’s squads personified Ramsay on the court. The names still fall off the lips, like lyrical raindrops, of most Big Five aficionados: Goukas, the ultimate passer; Billy Oakes, the streak-shooting lefty; Cliff Anderson, the 6’4” jumping-jack center with amazing pro-like moves; Tom Duff, the longshoreman power forward; Marty Ford, the skinny, finesse forward with the feathery touch.

“Yep,” Ramsay admits, “that was my finest college team. Their chemistry was uncanny—the feel, the sense of timing, the bonding they had for each other. They brought a perfect flow to the game.” Ramsay gets up from the kitchen table. He makes no more mention of that team. It was his last at St. Joe’s.

****

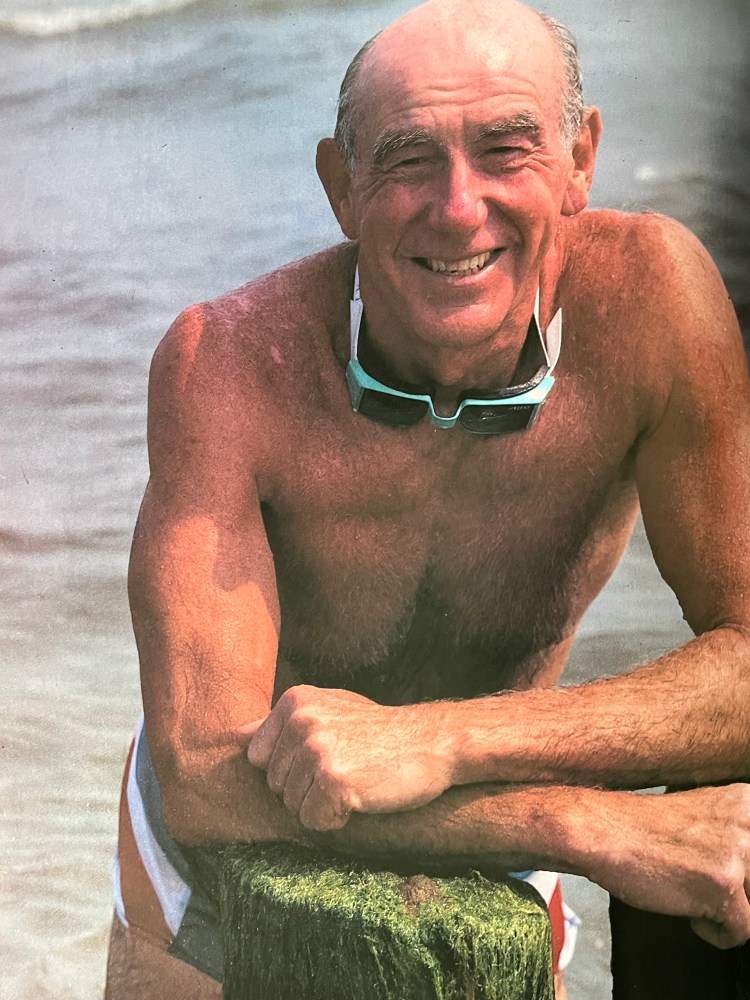

“I’m looking to do three hours, 10 minutes,” Jack Ramsay says as he stretches his quads in a blue wet suit. It is 7:30 A.M. Baltimore is buzzing. Over 2,000 triathletes have swarmed to Gunpowder Falls Park for the second-biggest triathlon on the East Coast: the Baltimore Bud Light U.S. Triathlon. Mike Pigg, the hot shot of the sport at the moment and the 1987 national champion, is here. So is Scott Tinley, two-time winner of the Ironman Triathlon in Hawaii. And so is 1987 Triathlete of the Year Kirsten Hanssen.

Nothing changes the fact, though, that it is a punishing day for a triathlon. It is sultry and tropically sunny, the kind of summer day meant more for loafing on a beach with a beer than swimming one mile, biking 25 miles, and running 6.2 miles. The temperature will get to 94 degrees, the humidity to 90 percent before it is over. Ramsay is worried. Does he have second thoughts about it?

“No, not at all,” he says. “It will just be tougher in the heat. My legs will feel as if they weigh 200 pounds each by the time I get to the run. I like it cool.” Ramsay laments that he has not been able to step up his training regimen since the basketball season ended. The NBA draft and the possibility of putting together trades have kept him close to his Pacers office. “I’m maybe 75 percent of what I want to be, condition-wise,” he says, “for somethings as physically testing as this.”

In the week leading up to the Baltimore triathlon, Ramsay averaged a mile a day in the pool, 15 miles a day on the bike, and three miles a day in roadwork. “Not nearly enough,” he says. “I’d like to do twice that much.” Ramsay will be calling in the chips on the foundation of fitness he has laid down over the years. Just two weeks ago, he completed a triathlon in Three Rivers, Mich., in 3:13. Today, with the heat, 3:10—his goal—looks unapproachable. Still, he won’t reduce his commitment to that number. “Last year,” he says, “I posted a 3:10 here.” He will be put to the ultimate gut check.

“Swimmers,” barks the starter through a bullhorn, “get ready.”

In triathlons, the swim event is always first. The start is staggered in waves—heat waves today—of 200, by age groups. Ramsay’s wave will be the last to go. The water is choppy, the current slapping in the faces of the swimmers.

Ramsay is passionate about triathlons. The burn hit in 1982. He was watching on television the Ironman Triathlon—a punishing 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike, and 26.2-mile run. He had never seen one, let along considered doing one. “I remember saying, ‘Now, that’s something that interests me,’” he recalls. That summer, he entered a local triathlon in Portland, where he was coaching the Trail Blazers at the time. It was not big time—a half-mile swim, 15-mile bike, and three-mile run. When he finished it, he was hooked.

He started to train In earnest for more challenging contests. One day, he would take a mile swim and do a 20-mile bike. Another day, he would do a 12-mile run and a half-mile swim. Some days, he put the whole package together. In between, he would pump iron.

In a way, he found salvation in triathlons. They forced him to deal with losing in another way. There was no conflict with winning. “I knew I couldn’t compete at a top level,” he says, pragmatically, “because I’m not that good in any one event. I am a decent swimmer, a decent biker, and a decent runner. Put them all together, and I’ll do okay—but I won’t win. But I can improve my performance.”

In 1987, he was good enough to finish 11th in his age group in the national championships at Hilton Head Island, S.C. “I was less than a minute away from the fifth-place finisher,” he says. Ramsay turned in a personal best time of 2:47 at Hilton Head.

****

He pushed off in the swim at 8:21. The temperature has risen dramatically in the last hour, nearing 90. Forty-three minutes later, he emerges from the water, his chest thumping, like a drumroll. He trots to the swim-bike transition area, peels off his wet suit, slips on his biking shoes, and breaks out on his spanking-new Trek bike.

The 25-mile bike route is laced with killer hills. With the sun beating down unmercifully on his bare back like a whip of fire, Ramsay struggles to take them in fast time. At the crest of one long hill, Ramsay drops his head, collapses his arms on the handlebars and coasts downhill.

When he gets to a long flat, he gears back up and puts the pedal hard to the hot asphalt—so hard the veins in his legs pop out like rope. “I really got focused at one point on the bike,” he says later. He passes 50 bikers. As he pedals by Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, home of the Orioles, he glances at the words chiseled deep into the wall at the front of the stadium: “TIME WILL NOT DIM THE GLORY OF THEIR DEEDS.”

Ramsay arrives at the bike-run transition area in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor at 10:33. He changes into running shoes. It is now a white-hot 92 degrees. Ramsay is not used to this. He pours water over his head before starting the long uphill run along William Street on the last leg of his punishing odyssey. His blue shorts drip as he races past one of the many rowhouse blocks of Baltimore. Church bells peal out to him, “Be Not Afraid.”

The crowds along the race route bark out encouraging words to him. Baltimore Is a lot like Philly, a city of neighborhoods—working-class wonderlands—where the men are happier than Heaven passing the day away shooting shots and beers in the many taprooms. Like Philly folks, they applaud the courage to conquer pain. Only their faces ask why?

The answer is mystical in a sense to Ramsay: the contours and contradictions of an imperfect life come together in this grueling competition. It is his way of conducting experiments in time and truth—he learns more about his limits and hopefully how to extend them. “It is why I will be doing five more of these things in the next two months,” he says before the race.

At the halfway point of the run—historic Fort McHenry—Ramsay is not seeking perfection. Survival is more like it. He Is shot, like a pugilist on rubber-band legs. He stops before entering the fort for the half-mile run around the grounds and walks in. “I was hurting at that point, really hurting,” he admits later. “Somewhat dazed.” Will he finish? Why would anyone want to do this to himself?

Coming into the final mile, Ramsay, naked with agony, hangs by a tough thread. He passes our Lady of Lourdes Church. The older women outside look perplexed at the blank, bovine stare in Ramsey’s eyes. He enters the inner harbor area and turns onto Rash Field for the final lap. He is now not only fighting fatigue but bleeding blisters on two toes.

As he comes down the final 25 yards, he gets a kick of energy from the more than 5,000 cheering spectators. His head is high, his legs flying, his arms pumping. From himself, he seeks always to stay the course. He crosses, pain and pleasure yoked to his face. Three hours and 15 minutes. Five minutes more than he had hoped and 15 degrees hotter than he expected.

Another 60-plus triathlete trots up as Ramsay is gulping down cup after cup of water. “Way to go, Jack,” he says. He looks at Ramsay’s fizzled-out figure for a long moment, then asks him, “Was it worth it?”

Ramsay simply smiles.