[The past several weeks have brought much chatter about the NBA’s sagging TV ratings. Many have zeroed in, again, to lament the oft-mentioned shortcomings of today’s NBA game. Those minuses include carrying the ball, too many three-point shots, too many Euro steps, too many uncontested layups, too many referee challenges, too few mid-range shots. .

Complaints about the state of the NBA game are nothing new in the league’s history. The best sports pundits from every era have weighed in, and I just found a fantastic case in point from the great Bob Ryan. Published in the February 1979 issue of Basketball Digest, Ryan tells it like it was, pre-Magic and Larry, pre-cable, pre-David Stern. He also keeps his analysis above the rumors back then of widespread drug use among the players.

What struck me here is Ryan’s line “the drive still happens to be the most exciting maneuver in basketball.” Reading that line today is just a remembrance of the obvious that gets buried under the barrage of three-point shots. If the league could turn down the threes a few notches and turn up the float from, say, the 1980s, maybe, just maybe, those NBA television ratings would trend upwards. I know they would in my household.]

****

Pat Williams, who has been the general manager of three NBA teams, says he’d still drive two hours through the snow and the rain to see an NBA game, “even if it were [lowly] Houston and Kansas City.” But then, Pat Williams could get enthusiastic about attending the Dover town meeting.

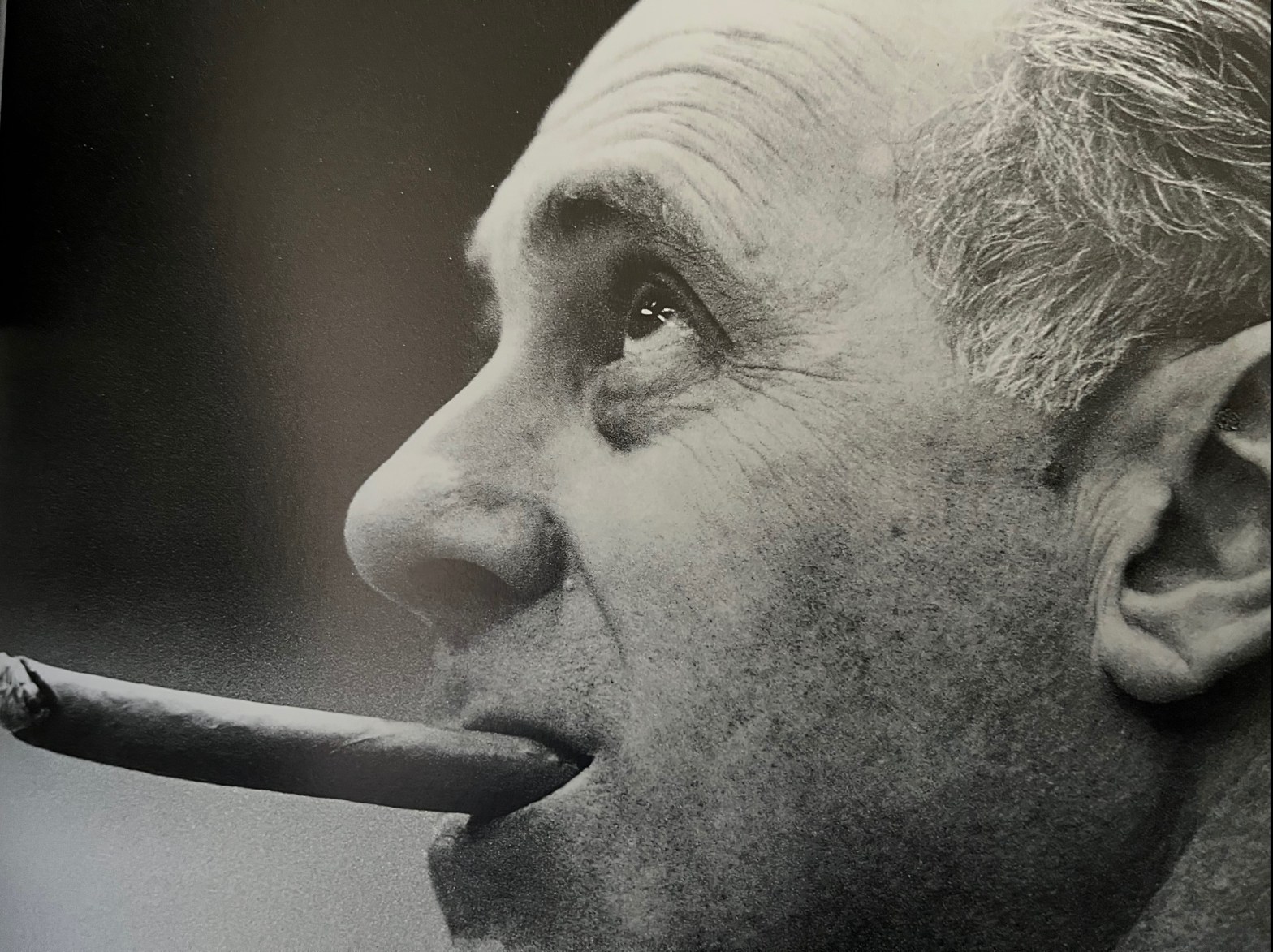

Red Auerbach, meanwhile, has been around professional basketball since shortly after the Franco-Prussian War, and he admits that the average game doesn’t grab him the way it used to. As the NBA runs through its 33rd season, a very pertinent question would be: Whatever happened to the “Sport of the Seventies”?

This was a Madison Avenue-type catchphrase applied to the NBA back of the dawn of this decade when, ‘tis said, the demographics, hieroglyphics, or whatever, pointed to basketball as being ready to explode onto the nation’s sporting consciousness, much as professional football did in the 1960s.

This was at the height of the NBA-ABA war, a conflict which succeeded only in elevating salaries and lowering the general standard of play. The NBA then had 14 franchises, the ABA 11. The merged league of 1978-79 has 22 franchises, at least three of which (New Jersey, Atlanta, and Kansas City) could fade away without fear that a legion of fans would drown in the backwash of tears. Clearly, there is a limit to the marketability of professional basketball. Even more clearly, the mucky-mucks at the top don’t know what it is.

There has been a great deal of hype since the merger of the two leagues to the effect that things have never been better, either on or off the floor. “All the stars are under one roof,” they say. That’s true, but the question is: What game are they playing?

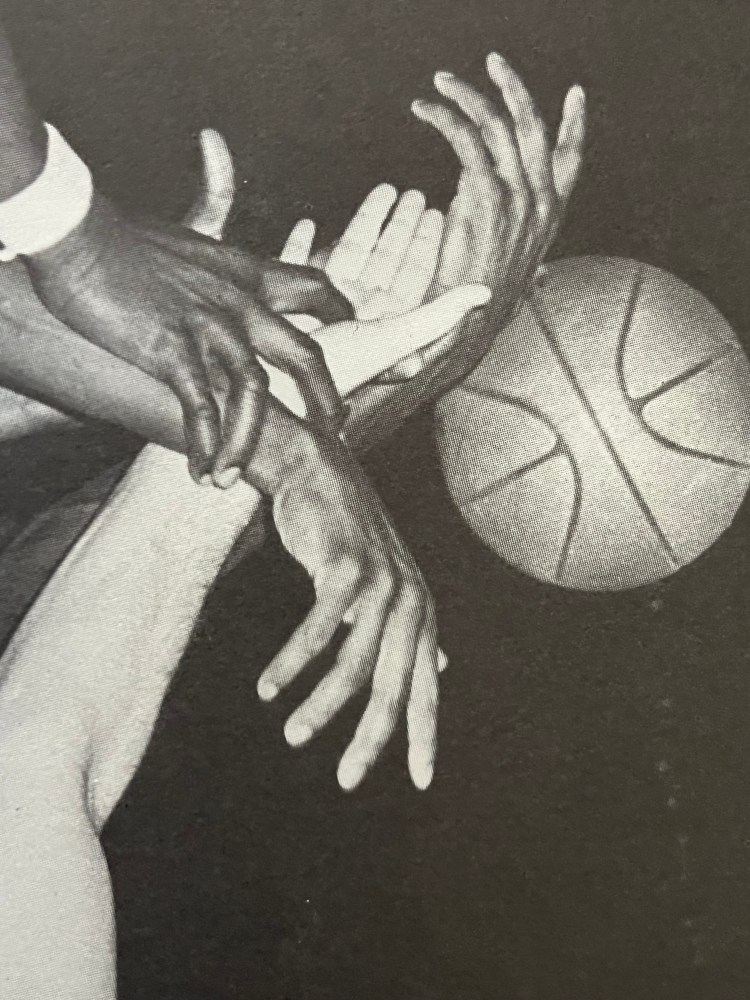

That people believe something is wrong with the product is evidenced by the fact that two highly significant role interpretations are supposed to be in effect this season. Concerned about the increase in legitimate violence and overall physical play in their league, the owners are now asking their officials to monitor the so-called “hand-checking,” which has always existed in the game.

Hence, defensive players may not keep “tactile contact” with opponents as a matter of course. The theory was that it had become increasingly difficult to keep fingertip contact from turning into outright-grabbing contact, the end result being defense was played with the hands, arms, and shoulders, rather than the feet, as it’s supposed to be played. In other words, there was a strong feeling that finesse had been suffering at the expense of muscle.

The second management concern is the zone defense, which though officially outlawed, has gained increasing popularity in the past few years. Allowing teams to “shade” their defense in what [official] Richie Powers might call a “zoning manner” means that (a) teams can’t get off decent shots within the required 24 seconds and (b) it is making the NBA strictly a jump-shooting league.

The paying customer loses on both points, because nobody, but some whacko high school coach pays to see defense alone, and the drive still happens to be the most exciting maneuver in basketball. The officials have been instructed to make defensive players guard people by enforcing the previously seldom invoked defensive three-second rule.

Not many patrons know it, but it has always been as illegal for a defensive player to station himself inside the foul line for longer than three seconds without guarding anyone as it has been for an offensive player to spend that amount of time in the area. If a defensive player is caught loitering in the lane by an official this season, the penalty is a technical foul assessed against his team. The old warning sanction exists no more. Justice is to be enacted swiftly.

Predictably, application of the rules depends on the whim of the individual officials. But they damn well better enforce these rules, since any owner worth his stock portfolio should want to see Dr. J taking off on great swooping drives, rather than taking turnaround jumpers.

Whether the enforcement of these rules will improve the product enough to stimulate a rise in television ratings is another matter, however. The disturbing fact is that despite rising revenues derived from a bizarre marriage with CBS, the NBA is losing popularity with the viewers. In head-to-head Sunday afternoon competition with NBC’s array of fine college games, for example, the NBA often has found itself outrated.

Different theories have been advanced for the declining interest in the average NBA telecast. The more vague, of course, is race. Who can possibly determine the number of white Americans bigoted enough to forgo watching a basketball game solely because an overwhelming majority of players is Black? They’re out there, however, probably in frightening numbers.

That sociological phenomenon aside, there is another obvious reason why the public appears to be souring on the NBA. Not enough men play the game hard.

“They’re just not hungry anymore,” sighs Auerbach. “The fundamental team discipline, isn’t there anymore either. Very few players seem to play because they love the game. Doug Collins is one. Tiny Archibald is another. Today, the only thing that matters is what kind of a contract you can get.”

The manifestation of this attitude is the players’ lack of game-to-game intensity. “You see a guy getting $500,000 a game,” Auerbach says, “and he still won’t go for a loose ball. What’s he saving it for?”

Motivation comes and goes. As Auerbach explains it, the pattern goes something like this:

Player X starts out in the $40,000-$50,000 range. He wants the big money, so he really puts out. He makes it into the six-figure class for three years and immediately starts to change. He wants more playing time. He wants more shots. He wants to be on national TV. He wants a suite on the road. All the while, he is doing less and less of the things which made him what he was.

“Guys in three-year contracts are predictable,” submits Auerbach. “In the second year, when they should be great, they are merely good. Then the third year, they turn it on because they’re thinking about becoming free agents and really earning the big money. But they’re still not playing the game the way they should. All of a sudden they’re careful. They don’t want to get hurt and blow the money. That’s a big problem. Few players will sacrifice themselves anymore.”

Think now of the average Sunday afternoon CBS telecast. You can’t say that the individual game is literally meaningless, per se, but with so many teams making the playoffs, it’s likely to be relatively unimportant. Four or five of the principals fall into Auerbach’s category of the non-hungry ballplayer. There are some gorgeous moves and a spiffy rejection or two, but basically the game lacks a feel.

Contrast this to the NBC college game. The gym will be packed. The cheerleaders will be gyrating. The bands will be playing. Some kid will be diving over the press table. And there will be talent on hand, too. The entire package will project a feeling, which leaves the viewer saying, “Boy, I wish I were there.” The only time the NBA generates this excitement is during the playoffs, and even then the ratings aren’t what they should be.

The NBA’s trappings are more impressive than ever, however, even if the product is somewhat tarnished. A legal-office staff, which once could be housed in a phone booth, now includes legal councils, marketing directors, directors of security, and assorted other corporate types. “Look back to the start of the 1970s,” says Williams, now in the second stint as GM of the 76ers, “and if you want to talk about the organization being much bigger and more complex, and the stakes being higher, you’d be absolutely correct. From the standpoint of this being a more professional product, from the arenas to the style of the uniforms to the quality of the press guides, it’s far ahead of what it was in those days years ago.”

But none of this means a thing when the official throws the ball up. The only thing which matters then is the ballgame itself, and the people who have been around the league for a while simply aren’t pleased with what they’ve been seeing.

There must be some reasons, for example, why only one team in last year’s league—the pre-injury Trail Blazers of 50-10—could have competed with five teams (Los Angeles, New York, Boston, Milwaukee, and Chicago) playing during the 1972-73 season. Is it the residual effect of the so-called Hardship Rule, which has infested the league with spoiled, incomplete, emotionally immature kids, some of whom have turned into surly, misguided adults?

Is it an abdication of responsibility on the part of high school and college coaches, some of whom may be allowing the charges to subsist on the 22-foot jumper, the magic cure-all for all offensive mistakes. Is it the greed described by Auerbach?

The irony of this situation is that there is more, not less, professional coaching today than ever before. No team is without an assistant coach. Most have two, and the Pistons now have three. Films are derigeur. Scouting is extensive.

Yet the style of coaching is also a tip-off that something is wrong. Take these nefarious zone defenses, for example. Every reputable basketball man on an amateur level will tell you that the ideal way to play basketball is with a good, aggressive man-to-man defense. A zone is designed to cover some weakness, whether it’s size, speed, or lack of depth (in which case you would want to eliminate the fouling out of the key player). If the pros are resorting to zones, it must mean the coaches don’t think their players can play man-to-man. (Remember, too, that the 24-second clock aids the team with the zone defense.) In other words, if there weren’t so many fundamentally poor defensive players, maybe there wouldn’t be so many teams employing zone defenses.

The NBA promise remains unfulfilled. No other team sport features such a collection of large, skilled athletes, and the NBA’s potential for satisfying visual and emotional appetites is enormous. When it clicks, as in the famous Phoenix-Boston Triple Overtime Game of 1976, the effect is awesome.

True, that game was a sports masterpiece and should not be held up as the standard. But neither should last year’s dreary Washington-Seattle finals be allowed to stand as a championship norm. There must be something wrong with the game when the entire playoffs of the world’s finest basketball league are played at such a consistently low level.

The game can be improved immediately if the hand-check and zone ordinances are enforced, but the larger issues of player motivation and training in fundamentals remain unresolved. The ultimate responsibility lies in the hands of neither of the administrators nor the coaches. If the NBA aspires to be the Sport of the Eighties, it’s the players who must elevate it to that height.

They blew the 1970s. Should we give them another chance in the 1980s.

Nearly every sport is just about keeps and stuff today

LikeLike