[Much has been written about Larry Bird and Magic Johnson entering the NBA in 1979 as two of the most celebrated rookies in years. One White, one Black; two marquee NBA franchises, two different styles of basketball. These factors helped to rekindle a bicoastal rivalry for the ages, while working wonders to popularize the pro game with more of the American sporting public. The power of Bird-Magic rivalry was also the league’s entre to more aggressively market its dueling superstars, not just its teams. Putting faces before the team nicknames also placed America on a first-name basis with Larry and Magic, a relationship that remains to this day.

Sometimes forgotten in this remembrance of the NBA’s past is what people were actually saying at the time. Magic Johnson, for instance, though viewed as a potentially game-changing talent, wasn’t necessarily hailed by everyone as a sure thing. Earvin was still very young, not much of a shooter or a defender, and the verdict was still out on whether he was quick enough to operate in an NBA backcourt.

For those who focused on the NBA and its troubled 1970s, the league’s most-profitable path forward wasn’t necessarily Bird and Magic. Bird and a rejuvenated Bill Walton was the better ticket. Two tall, dominant White dudes that the NBA could pitch with confidence to White America. Two White dudes who would help pro basketball cash in on its promise as “the Sport of the 1980s.”

In this article, published in the magazine Pro/College Basketball Scene, 1979-80, writer Bob Rubin touts the rise of Bird and Walton—and, in retrospect, gets the NBA’s future wrong. From my perspective, thankfully so. But Rubin raises the familiar litany of race-based arguments that were in play back then, making the traditional “White Hope” meme sound like common sense, even if it wasn’t and never could or should be.]

****

Consider this. In Miami, a good-sized city starved for big league sports, an NBA telecast was on CBS one Sunday afternoon last season. Among its opposition on TV was the Shirley Temple Theater on a local station. Yes, Shirley Temple defeated the pro basketball game in the ratings. Shirley Temple, for (Pistol) Pete’s sake!

That’s really big trouble for the NBA. And that is exactly what the National Basketball Association seems to be in.

What was once bravely proclaimed “The Sport of the 70s” is limping uncertainly toward 1980, beset by falling attendance and TV ratings; still burdened by a nonsensical, seemingly endless 82-game schedule; selling more Black heroes to a nation still grappling with race; hurt by a fat-cat lack of effort by players whom fans conclude are overpaid; damaged, ironically, by an overabundance of offensive talent that makes most games seem a monotonous parade of indefensible jump shots; and, finally, wounded by a lack of big-name stars.

What can be done about them?

League attendance was down a marginal 2 percent, but declined significantly and ominously more for its flagship franchises: New York and Los Angeles (11 percent), Philadelphia (19 percent), and Chicago (31 percent). The Knicks and Bulls had poor teams, so their sag is understandable, though no less painful, especially in the case of the vital Knick franchise. (“We definitely need a strong team in New York,” Houston president Ray Patterson said.) However, the Lakers and 76ers were contenders, so their box-office disappointments are not so easily explained.

“People I talk to around Los Angeles all tell me there isn’t a great deal of interest in either the Lakers or the NBA,” Lakers coach Jerry West admitted shortly before resigning in late June.

The NBA lost half its national TV audience in the six years that CBS has had broadcast rights. ABC Wide World of Sports, Superstars, Son of Superstars, Super Teams, Super Slobs, etc. and even NBC’s college basketball do better in the ratings.

In part, it’s due to the decline of traditionally popular clubs like the Knicks and Celtics. In part, it’s due to competition from cable TV, which last year televised over half the league’s 902 regular-season games. In part it’s due to CBS’ regionalization concept, which only served to deny much of the country of the schedule’s most-attractive matchup. In part, it’s due to inane CBS pregame and halftime features, such as H-O-R-S-E, One-on-One, Three-on-Three, and the Slam Dunk Contest. But mostly, it’s due to dullness.

In late June, the NBA approved the three-point basket that proved highly popular with fans in the old ABA. That should add unpredictability, tension, and excitement, particularly near the end of the game. Now, if the league could only do something about its schedule.

The NBA plays 82 regular-season games to eliminate only 10 of 22 teams from the playoffs. Many teams play the entire season with only a one-game homecourt playoff advantage as incentive. That, plus the body- and mind-breaking travel the players must endure almost guarantee lethargic play—if fat, multiple-year, no-cut contracts didn’t already rob the pros of the need to play hard all the time.

“They’re just not hungry anymore,” Celtic president and GM Red Auerbach said. “The fundamental team discipline isn’t there anymore, either. Very few players seem to play because they love the game. Doug Collins is one. Tiny Archibald is another. Today, the only thing that matters is what kind of a contract you can get.”

The players’ lethargy is contagious. Compare the ho-hum crowd response and the atmosphere at a regular-season pro game to the electricity you can feel right through your TV set when the college kids play on NBC. They’re playing for love, not money, and the difference is dramatically evident—to the detriment of the mercenaries.

The NBA has taken a positive step in increasing to 60 the number of games each team will play within its conference this year, which should enhance traditional rivalries and decrease the insane travel demands on the players.

Like many pro sports, the NBA ultimately lives and dies on the appeal of its stars, and in this vital area help appears on the way with the comeback of a veteran superstar and the emergence of a new one. Bill Walton and Larry Bird are huge, talented, charismatic (and white), and league officials are praying that their presence this season will turn the tide and start the NBA on the way back up.

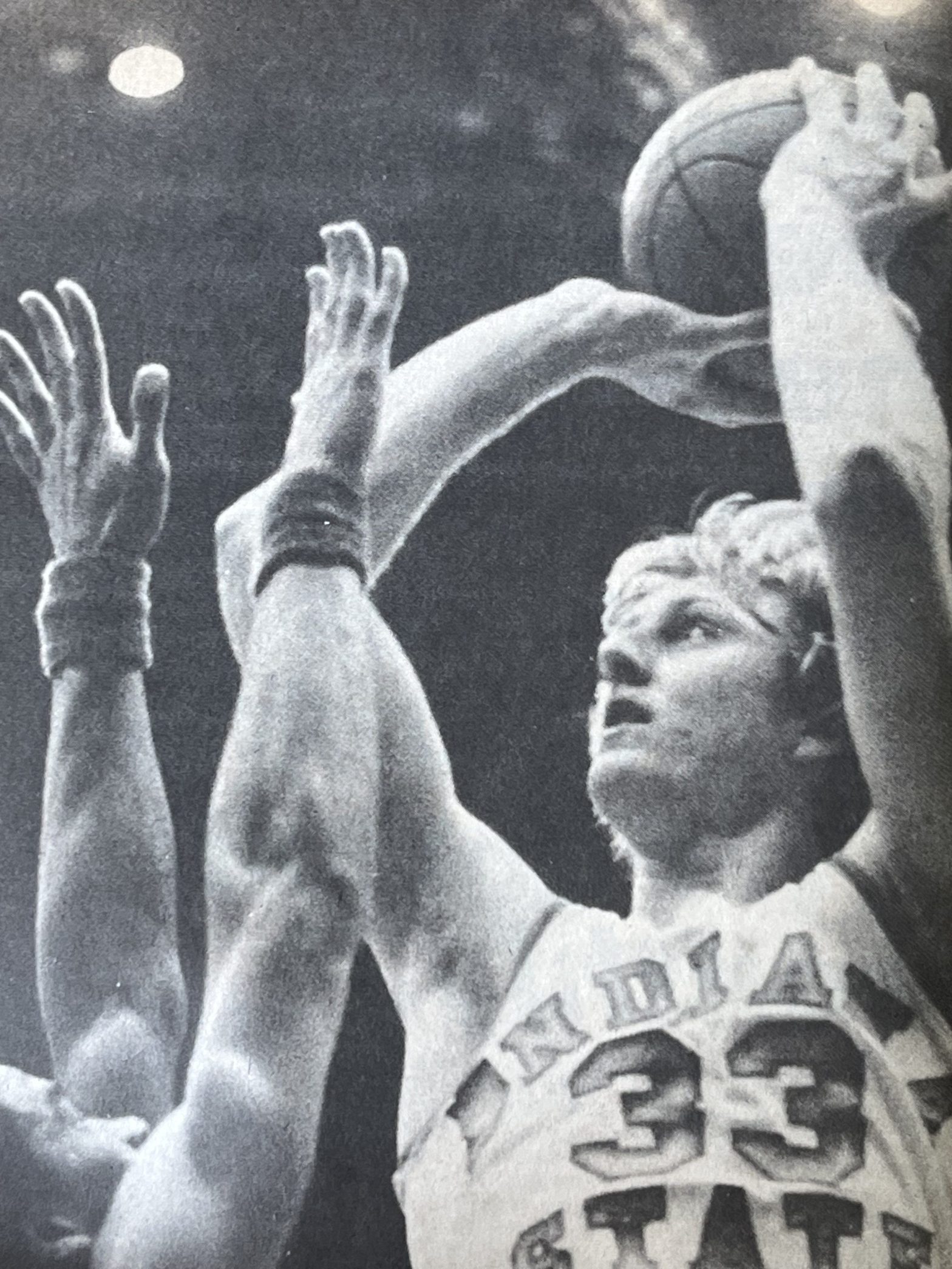

League-saving doesn’t come cheap. Walton, the 6-11 former UCLA All-American center who led Portland to the NBA title two years ago then was sidelined all last season with a foot injury, signed as a free agent with San Diego in May for seven years at a reported $1 million per, which made him the game’s highest paid player. Bird, a 6-9 All-American forward who was a near unanimous choice as the college Player of the Year for leading an unknown, lightly regarded Indiana State team to the NCAA championship final (a loss to Michigan State), signed a $3.25-million, five-year pact with the Celtics in June.

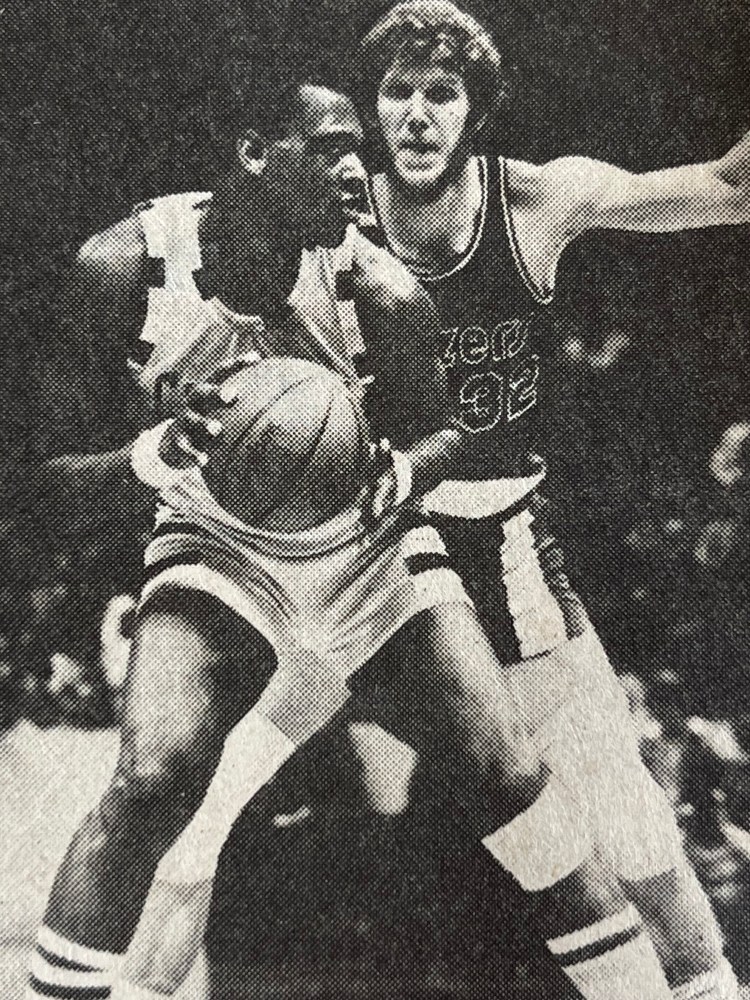

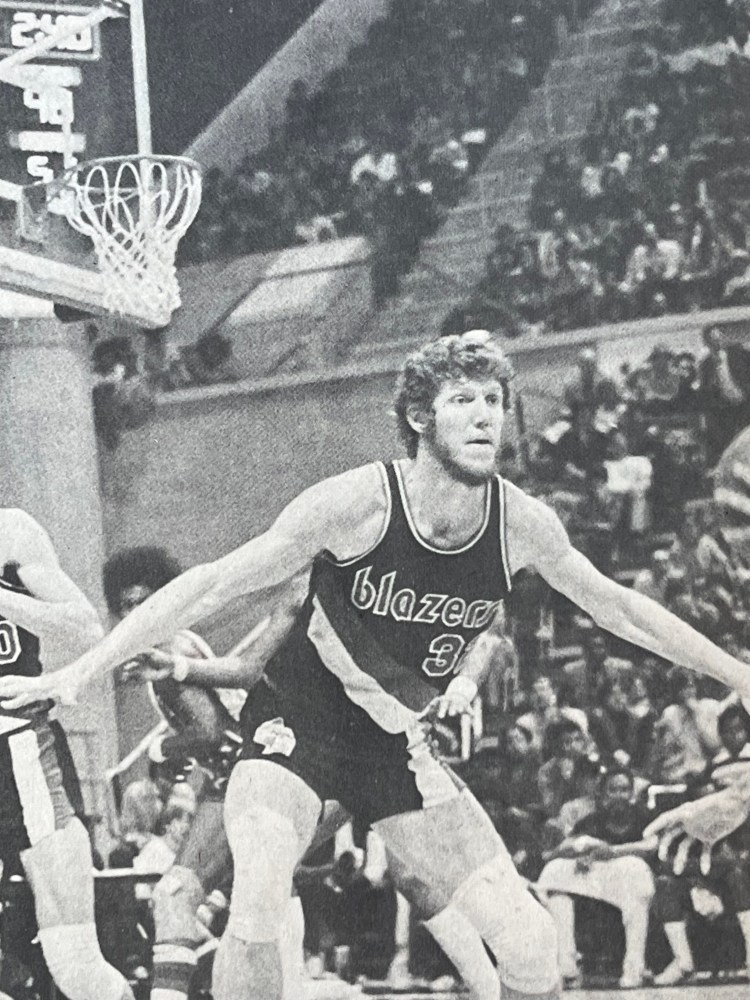

Watching Walton is a true fan’s delight. He plays both ends of the court the way the textbooks say the game should be played—scoring, rebounding, passing, and playing intimidating defense. The Trail Blazers had won 50 of 60 games in 1978 and were seemingly on their way to successfully defending their championship and justifying predictions of a budding dynasty when Walton suffered a stress fracture of the left foot in the second game of a playoff series against Seattle. The Blazers were finished without him, and when Walton subsequently accused the team of questionable medical practices in treating him, the big redhead decided he was finished with the Blazers.

Walton mulled where he should resume his career, ultimately declining the advances of the Knicks in favor of returning to his hometown San Diego, where he would have the chance to play in front of, and be close to, his family. He said he planned to complete his career with the Clippers.

It was a dramatically different Walton who greeted the press at his signing with the Clippers. His red beard was trimmed. His ponytail was gone. His faded jeans and flannel shirt had given way to a conservative three-piece suit. He seemed relaxed and at peace with the world, no longer the angry leftist ideologue who had alienated people with his outspokenly radical politics.

“You get older, you get smarter,” the 26-year-old giant said. “I have been playing basketball since I was eight years old. Suddenly, I had a year to think things over. You do a lot of thinking when you’re on crutches.”

Walton said his foot was fine and so were the prospects of a Clipper team with him on it. “I not only visualize a championship here, I expect it,” he said. “Not just one, either. The Clippers have great individual players. There are no limits to how great we can be.”

Led by the long-range bombs of guard Lloyd “All-World” Free, the Clippers won 43 games and were one of the league’s pleasant surprises last season. Now with a dominant big man inside, happy fans and happy coach Gene Shue are looking quicker for bigger and better. The team hired a skywriting airplane the day Walton came aboard. A giant message—“Walton is a Clipper”—was spelled out in smoke above crowded San Diego beaches and San Diego Stadium, where the Padres were playing host to the Mets.

“Bill Walton is the greatest big man ever to play this game,” Shue had said two years ago when, as coach of the Philadelphia 76ers, he was beaten by the Walton-led Trail Blazers in the NBA finals. “He doesn’t have any weaknesses. I’d love to have him.”

Now he does, and Big Bill’s return to action was applauded even by Clipper opponents, who fully realize the fan appeal he brings back with him to the entire league.

****

Walton has proven himself. Larry Bird hasn’t, but you won’t find an NBA executive who doubts that he will. Like Walton, he is a complete player, able to score from inside and outside, rebound, and play defense (though a lack of quickness may hurt him some). But Bird gets most of his raves for his intelligence, court sense, unselfishness, and his passing, unusual qualities to single out about a 6-9 power forward, who averaged 32.8, 30, and 29 points per game for Indiana State on a career field-goal percentage of 53.2.

Laker general manager Bill Sharman calls Bird “one of the best college forwards I have ever seen.” Slick Leonard, coach and general manager of the Indiana Pacers, says, “I’ve seen two great passing forwards in my time. Rick Barry is one, and Larry Bird is the other. Bird seems to see guys before he even gets the ball.”

Auerbach calls him “the greatest passing forward I’ve ever seen,” and he has seen them all. “When he gets anywhere near the ball,” Auerbach says, “it belongs to him. He has a great concept of the game of basketball and a great feel of what’s going on between the foul lines.”

“Normally, it isn’t Larry’s scoring that beat you,” says Creighton coach Tom Apke. “It’s his ability to pass and create opportunities for other players.”

Carl Nicks, Indiana State’s junior guard, learned to expect the unexpected from Bird. “You’ve got to watch him every minute,” he said, “or he’ll hit you in the nose with the ball. He realizes he can’t do it alone. He knows he can score almost at will, and yet he’s always ready to pass off as if to make sure we don’t get away from the teamplay concept. He’s not outspoken by any means, and he’s not out to show that he’s great.”

But he is great. Al McGuire, Marquette coach-turned-NBC sportscaster, calls Bird, “the Great White Hope for the NBA,” and unfortunately he’s only half joking. Seventy-five percent of the league is Black, while more than 75 percent of the fans are White. It shouldn’t matter, but it does.

With the retirement of West, John Havlicek, Dave DeBusschere, Bill Bradley, and other White stars in recent years, and the health problems of Peter Maravich, Black players are even more dominant among the superstars. A percentage of White fans are turned off by it.

“This is something we must no longer whisper about,” says Denver general manager Carl Scheer. “It’s definitely a problem, and we, the owners, created it. People see our players as being overpaid and underworked, and the majority of them are Black.”

“It is a fact that White people in general look unfavorably upon Blacks who are making astronomical amounts of money, if it appears they are not working hard for that money,” says Seattle’s Paul Silas, a Black veteran who is president of the NBA Players Association. “Our players have become so good that it appears they’re doing things too easily that they don’t have the intensity they once had.”

Some people admit they are turned off by the NBA for racial reasons. Others couch the explanation in more palatable—but essentially identical—terms. “A lot of people use the word ‘undisciplined’ to describe the NBA,” says Al Attles, coach of the Golden State Warriors. “I think that word is pointed at a group more than at a sport. What do they mean by it? On the court? Off the court? What kind of clothes a guy wears? How he talks? How he plays? I think that’s a cop-out.”

The Knicks fielded an all-Black starting team last season. “It’s a subject that has never been formalized, but it’s there,” New York president Mike Burke said. “Many fans have asked when we are going to put some White players on the court. What can I say? Black players play the game better. Here in New York, we’re much more tolerant of the situation. Out West, I believe clubs recruit more Whites, because that’s what their fans demand. We are less prejudiced. No, that’s too strong a word—it’s identification with an athlete.”

Fans of any color can identify with the classic skills displayed by Walton and Bird. “There are so few outstanding White players in our league. They are very rare,” says Pat Williams, the 76ers’ vice president and general manager. “That makes Bird and Walton assets. But with them, skin color is a secondary issue. If they were green, you’d still make a great effort to get them.”

The Clippers and Celtics paid a fortune to get them. Now, they and the rest of the league can only hope Walton and Bird get back the fans and make pro basketball “The Sport of the 1980s.”