[Here’s a look back at the late-great Maurice Lucas during the 1976-77 season, or right after the NBA-ABA merger. Lucas has joined the Portland Trail Blazers, where he’s emerged as one of the league’s top big forwards and feared tough guys.

The first article, which is real brief, sets the stage for Lucas’ emergence in Portland. It’s pulled from the June 1977 issue of Basketball Digest. At the keyboard is Reb Bochat, then with the Milwaukee Sentinel. To follow, I’ve got two even-better, late-season stories about Lucas and his fists.]

****

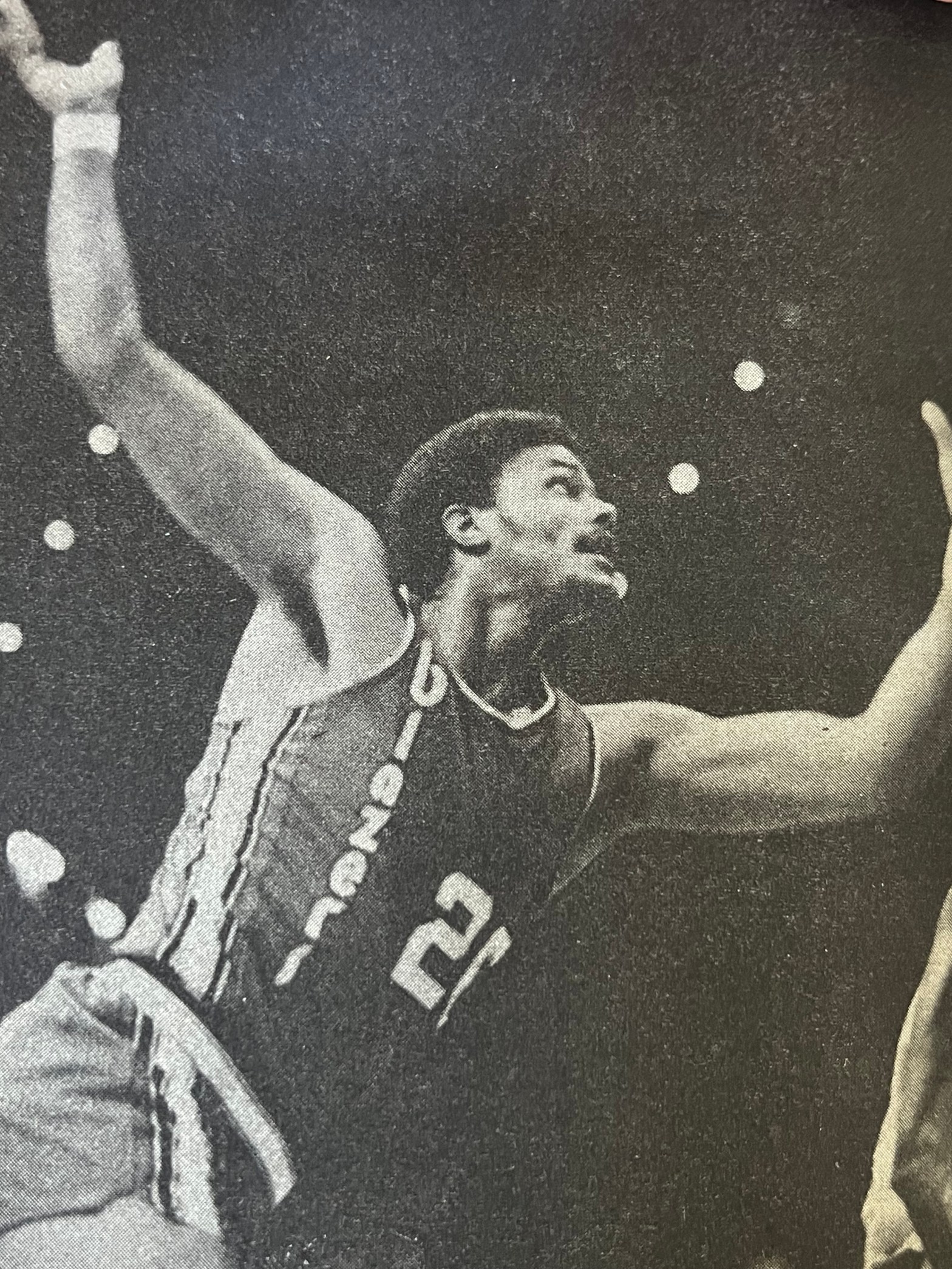

The man has a reputation for being very rough . . . and very, very tough. Among his knockout victims is 7-2 Artis Gilmore. Yet, says Maurice Lucas, “I don’t look for a fight. There’s always going to be a lot of body contact (in pro basketball), and a lot of people get upset.”

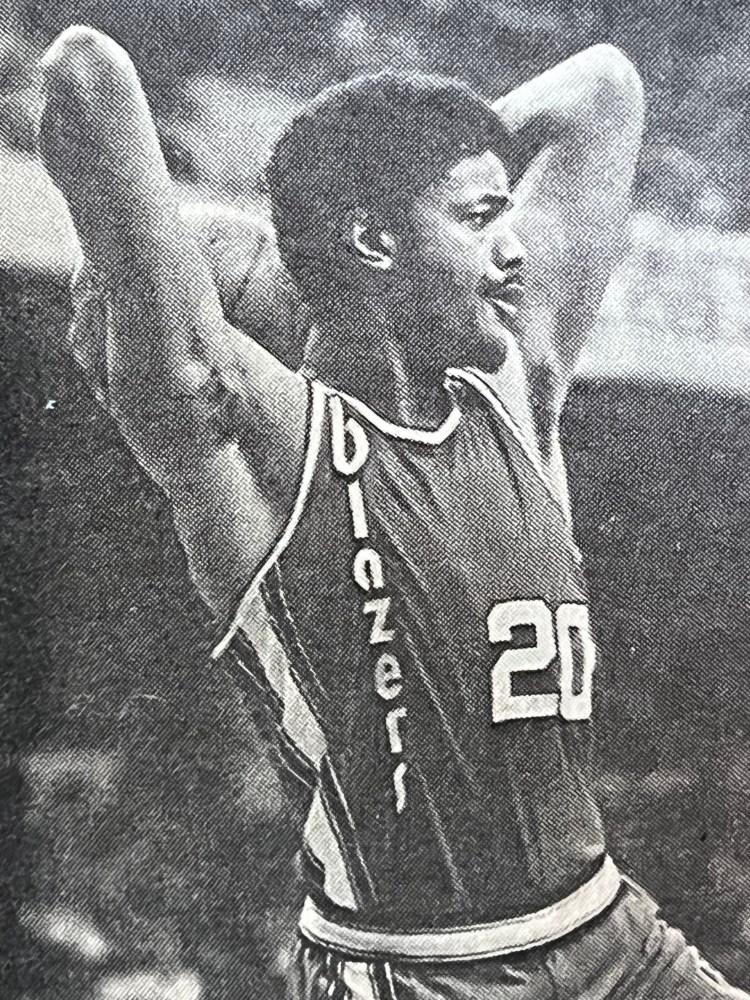

Lucas, the former Marquette University star, looks as fit as a bear in his red Portland Trail Blazers uniform. At 6-9 and 223 pounds, he has a reputation for being a man nobody looks to mess around with on a basketball court. A very aggressive rebounder, Lucas said, “I try to play hard. If that means being physical, that’s what I am.”

The press book of the now defunct ABA Spirits of St. Louis, where Lucas began his pro career after passing up his remaining eligibility at Marquette, described him as a player with “no nonsense aggressiveness on the court. Anyone who was not ready to play the same way in Lucas’ presence was going to leave bruised and beaten.”

Lucas discounts some of that reputation. “Nobody says (Dave) Cowens goes looking for fights. But the way he plays, you can get your head run over.”

Lucas prides himself on being a complete basketball player, and he can get the points as well as anyone. He’s been averaging more than 20 points a game in Portland. The Blazers are among the highest-scoring teams in the league, yet Lucas is the team’s only player among the top 20 scorers. He also ranks among the NBA’s best rebounders with an average of almost 12 a game.

In the ABA, Lucas averaged 13.2 points as a rookie and 16.9 last season. Last year, he hauled down 970 rebounds, second only to Gilmore.

The Blazers acquired him as the second player picked in the 1976 ABA dispersal draft. ”I like to play similar to a Paul Silas (the former Celtic strongman)—with a couple of added features, like scoring,” noted Lucas.

“A big thing is I’ve been very fortunate, both in college and pro ball, not to have sustained any major injuries,” Lucas pointed out. “I’ve had a lot of ankle injuries and a lot of sore knees, along with the usual bruises. But I’ve stayed pretty healthy.”

Lucas said, “One of the keys to being successful in the pros is how you eat and sleep, especially on the road. You learn to sleep on airplanes and anytime you get a chance. You get to know how to do it. And you feed your body well, which is easier to do than in college because you have the money.

“College ball was difficult in another aspect. You still have to get up in the mornings and go to school. Here, it’s up to you to take care of what you’ve got to do to be able to perform at your best. “

Lucas plays strong forward for Portland, although he does play some center, either when 6-11 Bill Walton is on the sidelines or when the Blazers go to a double pivot.

Noted Lucas, the difference between the NBA and the ABA, where he played two seasons for St. Louis and the Kentucky Colonels, is that “basically they (the NBA) have bigger centers and more of them. You’d see a lot of 6-8 and 6-9 guys in the middle. It’s not really different physically, but you have big guys like Kareem (Abdul-Jabbar), Bob McAdoo, and Bob Lanier, and the strong guys like Wes Unseld, Sam Lacey, and Cowens.”

Lucas said that among the things he likes better about the NBA than the ABA are “the bigger cities, a more organized setup, and you don’t have to face the same team so often. You’ll see a lot of new faces.” (in the 22-team NBA, teams face each other only four times, whereas in the dwindling days of the ABA, teams could meet that often in a two-week span.)

[Up next is a playoff profile of Lucas from the entertaining Pete Alfano of Newsday. The article ran on May 31, 1977. Enjoy!]

There was a night in Chicago this season when Maurice Lucas punched Artis Gilmore and sent the seven-footer skidding across the basketball court. Then Lucas saw Bulls assistant coach Gene Tormohlen with his hands around Herm Gilliam’s neck. Lucas intervened on behalf of his teammate.

“In Chicago,” Maurice Lucas says, “ they just said, ‘Lucas is going crazy again.’”

Last Thursday, in Philadelphia, Lucas came to the aid of Bob Gross and squared off against Darryl Dawkins. The fight cost him $2,500, which was the fine levied by NBA commissioner Larry O’Brien. In the same game, Lucas had words with George McGinnis. And once, while running down the court, Lucas’ hands were slapped by Julius Erving.

The impression Maurice Lucas is making in his first season in the NBA is mostly with his fists. This is not, he says, what he had in mind. He averaged 20 points during the regular season and was the Trail Blazers’ leading scorer. No, it was not Bill Walton, it was Lucas. He is annoyed that more people are not aware of that.

He averaged 11 rebounds, too. He may be the Blazers’ best one-on-one player. And his defense, according to assistant coach Jack McKinney, initially was weak but has improved steadily.

Still, there were those fights. People always want to talk about the fights. “I like to work with youngsters,” Lucas said. “I have a rapport with them. But young guys come up to me and say, ‘I want to be like you and punch people out.’ I tell them that’s not the approach.”

Lucas is a man of contrasting moods. He is a man of contradictions. He is quiet, apparently a sensitive person who dislikes being called “Big Mo”—“Call me Maurice, please.” His voice rarely rises above a whisper.

He smiles easily and often for teammates and for kids, who stand outside the locker room waiting for autographs. On the court, however, the smile becomes a glare. He plays aggressively, and critics say he plays dirty. “I play very aggressively. I play with intelligence,” he said. He paused a moment and added a footnote. “I play rough.”

Lucas played for Al McGuire at Marquette, but applied as a hardship case after his junior year. He signed with the ABA and played for St. Louis and Kentucky. In the ABA dispersal draft, he was selected by Portland in the first round.

Combining with Walton—who was healthy for most of the season—Lucas helped lead the Blazers to their first playoff berth ever. He complements Walton in the frontcourt. At 6-9 and 218 pounds, he gives the Blazers two formidable rebounders. It enables Gross, the small forward, to work the perimeter and to concentrate on the fastbreak. “There’s no pressure on me to rebound,” Gross said. “Bill and Maurice are so good at it.”

The Blazers have taken this road to the NBA finals against the Philadelphia 76ers. Seemingly, Lucas would welcome the playoff exposure, which would enable him to receive the publicity Walton hogged during the season.

“I shy away from trying to be a superstar,” Lucas said. “I can’t say, I’m shy, but I lean away from people. I enjoy privacy. I’d rather be thought of as part of the team.”

Those are also Walton’s words and coach Jack Ramsay’s words. The philosophy is as much a part of the Blazers’ strategy as any of their plays. Recognition will come gradually for Lucas. The championship this season will speed the process.

“Now I get more publicity from that fight with Dawkins than I did all season,” he said. “I’ve done well, and I never received publicity. After the Gilmore thing, I became ‘The Enforcer.’ I don’t try to intimidate people. Usually, when I get in a fight, it’s because I was helping a teammate. This time, it was an expensive habit.”

[About that fight with Dawkins. Up next is a fantastic column, titled “City of Brotherly POW,” by from the Philadelphia Inquirer’s great Frank Dolson. His blow-by-blow ran on May 27, 1979 and offers some fistic food for thought as we watch today’s NBA stars push-and-shove-and cheap shot in the 2025 NBA playoffs.]

It started as a basketball game—a great one for the 76ers, a terrible one for the Trail Blazers. Then, with 4 minutes, 52 seconds left on the clock, it turned into something ugly and frightening.

One minute Philadelphia’s Darryl Dawkins and Portland’s Bob Gross were going for a rebound under the Trail Blazers’ basket. “He had the ball,” Gross said. “I came up, got my hand on it, and he swung me down. He tried to be rough about it. Somebody grabbed him, and Doug (Collins) kinda grabbed me. I thought it was over . . .”

Instead, it was just the beginning of one of those incidents that happens too frequently in high-stakes professional athletics. We saw it four years ago in the National League playoff at Shea Stadium—a terrifying mob scene with players using baseball bats to protect themselves from crazed spectators. And last night, we saw it at the Spectrum while a national television audience stared at their screens and shook their heads, and probably said, “City of Brotherly Love, eh?”

Before this latest horror show in the name of sport had ended, Dawkins—the mountainous manchild who has done so much for the 76ers in recent weeks—threw a wild left at Gross . . . and hit Collins, his slender, peace-loving teammate above the right eye; Maurice Lucas had charged up from behind and taken a shot at Dawkins . . . and the NBA championship playoffs suddenly bore a sickening resemblance to one of those Toronto-Philadelphia hockey bloodfests.

“I don’t think this is the way basketball is or should be,” Collins said later after the cut over his eye had been closed with four stitches. “Hockey players are smaller, and they’re on ice. Let Darryl Dawkins or Maurice Lucas hit you . . .”

The mere thought is scary. The sight of those two monsters squaring off with their fists raised high, with hatred in their eyes, was a little short of terrifying. “The thing that scared me,” Portland assistant coach Jack McKinney said, “Luke had just lost control . . .”

So had Dawkins—and so did some of the fans.

Spectators, some of them swinging wildly, policemen, ushers, players, and coaches, all were on the court in a matter of seconds. Jack Ramsay, the intensely emotional—and bitterly disappointed Blazer head coach—charged into the middle of the mob, heading straight for Dawkins, trying to get him to back off. Luckily, the furious young man only shoved Ramsay, who could have been torn apart, if not by Dawkins, then by those crazed spectators.

“That’s the least of my concerns,” Jack said. “I’m not afraid of any of those people.”

Neither was McKinney. Hell, there was no time to be scared. The assistant wound up in a wrestling match with a green-shirted fan who had taken a swing at one of the Blazers. “He came out and hit a player in the back of the neck,” McKinney said. “That really ticked me off. Stupid fans. I grabbed him.”

The fan was finally dragged off the court, his shirt ripped off his back. “It was (ugly), and it shouldn’t be,” Ramsay was saying through clenched teeth in the losing locker room. “There was an obvious lack of security. When fans run out on the floor, there’s got to be a lack of security.”

Also a lack of sense.

“Some of those fans are nuts,” Portland’s Corky Calhoun said. “You could get killed out there.”

Clearly, the thought had struck Julius Erving and Doug Collins as well. At the height of the wild mob scene, Erving sat on the floor near midcourt, a nonviolent observer, and Collins, the blood rushing down his face, headed for cover. “I felt it bleeding,” Doug said. “I got out of the way. Those big guys were going wild.”

One of them—Mr. Dawkins—was still wild when the brawl, and the game, had ended. Incensed over Lucas’ attack from the rear, Dawkins entered the 76ers’ locker room in a rage, slammed down a metal partition in the bathroom and let his feelings pour out a torrent of venom. “I’m mad at my blankety-blank teammates,” the kid raved. “They let a damn man sneak up behind me and hit me in the back.”

“He’s just hot,” Doug Collins said. “It’s all in the heat of battle.”

You could practically see the smoke, Dawkins was so hot. Dressing quickly, he stomped out of the locker room, ignored efforts to stop him, and was marching down the corridor at the very moment Ramsay opened the Portland locker room.

Half an hour later, Collins—the man Dawkins had accidentally slugged—was still flat on his back in the trainer’s room, an ice bag pressed against his right eye and another one on his leg. “I’ve got a sprained ankle, a pulled muscle in my leg, and five (actually four) stitches in my eye,” Doug said when he finally emerged, looking more like a battered fighter than a winning basketball player. What a shame that the 76ers’ big night had to end