[They called him “Dollar Bill” after he signed his then-mega-contract in 1967 to star for the New York Knicks. But New York soon called Bill Bradley a lot of other things in his early struggle to live up all those dollar bills. In this article, from the March 1970 issue of New York Jock magazine, sportswriter Dave Klein has some fun and seriousness with New York’s favorite Rhodes Scholar on the rise and now living Life on the Run. Klein, who passed away last month at age 82, was a staple at the Newark Star-Ledger, known for his quick wit, staunch opinions, and die-hard coverage of the New York football Giants. Here’s to another career well done.]

****

People who were witnesses to the drama from the very beginning, sometimes find it a little difficult to reconcile the images they have of Bill Bradley. They still remember him as Princeton Bill. The gangling kid from Crystal City, Mo., Rhodes Scholar, All-American, and folklore at age 19. Some of Oscar Robertson, some of Bob Cousy, smarter than anybody. Wavy black hair and a boyish, shy, impishly-cute grin. Nice to everybody and “mister” to everybody.

They remember, these special few, Princeton’s Dillon Gym, now abandoned for the glass-and-steel shell called Jadwyn Fieldhouse. And little preliminary things like parking the car on Princeton’s Main Street, just off Nassau, and roast beef on rye and a beer in a little basement restaurant with the long, rough, wooden tables. And walking across campus through the cutting wind of a winter’s night to see a game of Ivy League basketball as played by gentleman given to remarking, “Excuse me” and “Good shot, old man.”

That was the Ivy game, and Bill Bradley fit into it comfortably, as politely Princetonian as anybody, bringing to the winter evenings nothing more radical, nothing more tradition-shattering than his own sheer artistry, which was quite enough to make the elders at the Institute for Advanced Studies blow their high-domed cool right along with the delirious undergraduates.

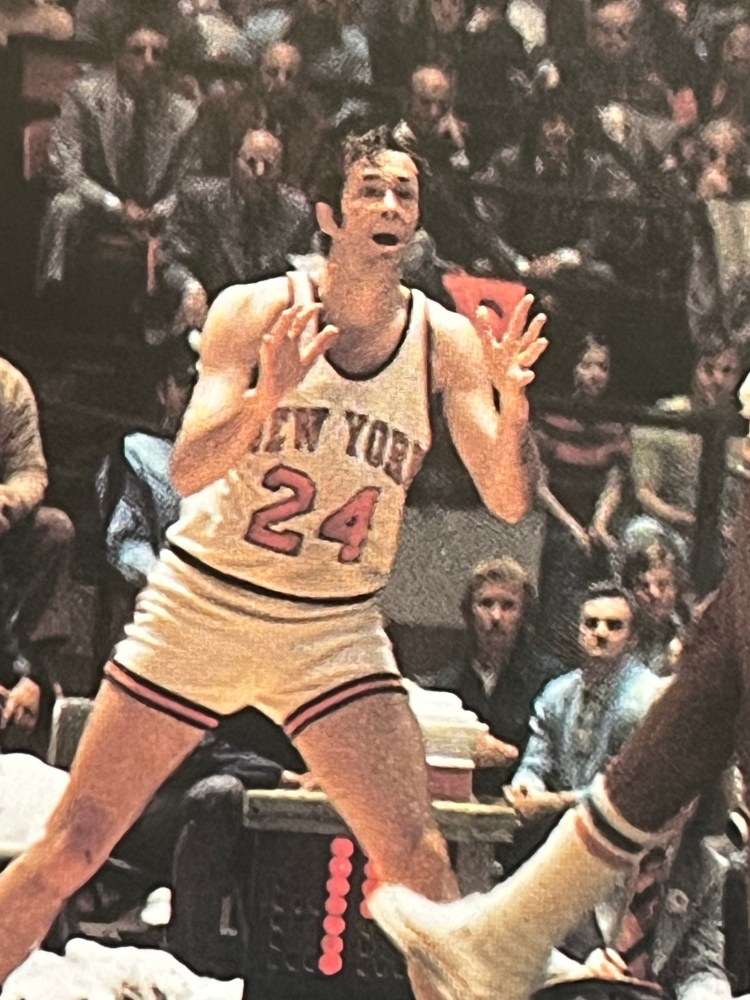

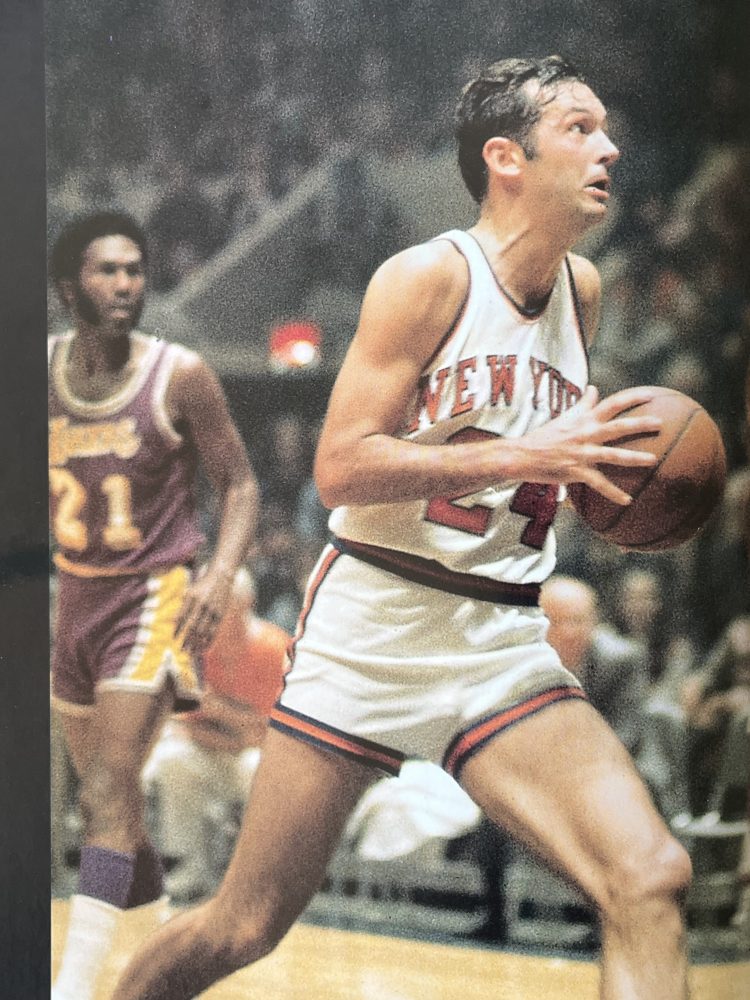

That was yesterday’s image. Today, Bill Bradley is polished wood glaring back up at the court lights at Madison Square Garden. He is the incredible noise that swells and boils and surrounds and presents his every move. He is the lure to many of the nineteen-five who fill the seats and pay the too-high prices and make the team genuine New York. He is the soft, two-handed, almost delicate jump shot, which goes in far more often than not and which rustles the net with a gentleman’s polite but firm perfection. Never the rim for Bill Bradley.

Today it is Bill Bradley of the New York Knicks, the 6-5 forward who is right at home among players who went to Iowa State and Texas Western and Arizona, who has cracked the starting lineup of the best basketball team in the world after his days in a scholars chair at Oxford.

Today’s Bill Bradley throws his elbows and swears once in a while and takes the ribbing and makes Coach Red Holtzman, who is pure New York, sit back and smile at the honest-to-God “goyisha chutzpa” with which the kid operates. Bill Bradley smiles with a warm, honest, friendly glow, and you are aware that if his hand were picking your pocket or slicing your jugular, he would actually make you like it.

How did Bill Bradley do it? It wasn’t easy.

“When I got here, I listened to all those people who talked to me about contact in pro ball,” he said one day in his Manhattan apartment. “When they said I couldn’t take it, well, that wasn’t right. I had to adjust to some extent, and it did take a while. But it isn’t all that people made of it. It’s like playing high school ball and then getting into the summer playground games with the college guys. There’s more contact there, a lot more.

“But you have to adjust to it, and you can. It takes a lot more up here, but I was ready to try it or else I never would have. It’s all relative to the level at which you feel you can play effectively.”

Maybe so. But Bill Bradley seldom felt the dig of a sharp elbow or the jab of a determined knee when he played for Bill van Breda Kolff. There were few times he had to fight back, when the competition was good enough and classy enough to really challenge him. Sure, there was that impossible run for the NCAA championship in 1965 and that torrid Holiday Festival [Tournament] and the game with Cazzie’s Michigan crew in 1964, but mostly the kids who played against Princeton Bill were content to watch him, were as much in awe of his gifts and his magnetism as those who paid to watch.

And when was the last time a stacked house showed up rooting wildly, ferociously, for St. Joe’s and wound up giving a sissy-boy from Princeton a standing ovation? Just once. But it must remain suspect because he had just fouled out after destroying the Hawks, and perhaps those practical Philadelphia realists were cheering that.

“I remember him most for a game in the NCAA regionals,” says Mike Riordan, now a Knick, then at Providence. “We had to beat St. Joe’s to get past the regional semi, and everybody said the winner of that one would go straight to the national final, and we really thought we could take the title. We had lost just once all year, to St. Joe’s. They had lost maybe twice. And we beat ‘em that Friday night.

“And Princeton had won its game with North Carolina State, and we figured that was good for us. A break. You know, the Ivy League. We had Jimmy Walker and height and a damned good team. Then we went out there Saturday night, and he went right for our throats.”

What Bill did was take four kids who only knew from private schools and butlers and made them believe they were gutter fighters. He even made them believe they were basketball players, which was tougher. And he was all over the court, shooting the good shots, finding gawky-boys-turned-Tigers all alone underneath, rebounding, and playmaking and making it work.

“At the half,” Riordan added, “Coach Mullaney could only tell us, ‘Don’t stand around watching him. The son-of-a-bitch is hypnotizing you.’ He was right. Bradley was definitely hypnotizing us.”

The final score was ridiculous, like 109-69, and Providence had been favored by 20, and nothing like that ever happened to Joe Mullaney before . . . or since. “Ivy League?” Mullaney roared that night. “Ivy League my foot. They kicked the tar out of us, and he personally beat our brains out. That kid is fantastic. You know, I would catch myself staring at him, too, on the bench. I was getting hypnotized, too.”

This is all nonsense, of course. Nobody does things like that in the Ivy League. And after the officials had jobbed Princeton in the semifinal against Michigan, and after Bill had scored a record 58 points in the consolation against Wichita State, he took the Rhodes scholarship and left the country.

He played some European basketball just to stay in shape, and nobody really laughed when the Knicks drafted him first because they couldn’t afford not to, but nobody ever figured he would make it. Nobody can make the NBA out of places like Princeton and Oxford. Right? Wrong.

“I never thought Bill would have much trouble once he knew exactly what it was they wanted of him up here,” says van Breda Kolff, who now coaches the Pistons and regularly gets zapped by the kid he used to teach. “He could have made it big at Duke or Kentucky or UCLA, or anywhere else. But he dug the Princeton education because he knew all along he was going to become a Rhodes Scholar.

“And I’ve always been kind of afraid to ask him if he wants to be President. Because if he says, yes, I know he will and I’ll vote for him, and that would kind of take the suspense out of it.” Bradley denies this part of his legend—does not like it, in fact—and insists he has not planned every step of his life. “No, I’m not doling out a certain number of years to pro ball. I don’t have a final goal for myself.”

But others insist he has political advisers, and he is waiting for the right opportunity. He denies it. But so does [NFL quarterback] Francis Tarkenton, who will no doubt run against him. And Bill’s graduate thesis in history was on Harry Truman’s 1940 Senatorial campaign in Missouri.

But for now, the professionalization is intriguing. It is not nearly finished, Bradley claims. “I’m just beginning to know what my function is,” he explains. “I’m always learning something about my game. You must determine how you relate to the team and then decide what role you must fill in making it a better team. Points are not important, not if you think of basketball as a team game, a group effort. And I do.

“I shoot if I have the shot because I always did. That’s part of my job. But I’d just as soon make a good pass or take down an important rebound. It’s relative to what the team needs, and the needs of the team are always more important than one player. Points, just for the sake of scoring them, would serve no purpose. They would be without meaning.”

So now Bill Bradley is closer to his final image. “I can still improve. I have to with each game if I’m doing it right. Practice isn’t boring because it’s a chance to work at the things you have to do right during the game. And improving doesn’t mean gaining new moves. I can work on the same move hundreds of times and know it isn’t right just yet, but I feel confident it will get to be right. I have to think that way, because this is a big game made up a very small arts.”

Bill Bradley started with the Knicks as a guard—“It was very strange”—and was shifted back to forward when Cazzie Russell broke his ankle in the early part of the 1968-69 season. And people said, “Well, now they’ll get him. How can he cover the forwards, the ones like Billy Cunningham and Gus Johnson and Jim Washington?”

But they didn’t get him, not at all. He stuck it to them. He learned to play defense, and he soon had the name through the league. “Don’t hit the Princeton kid, he hits back,” they said, “and dear God, don’t let him get clear because he never misses when he’s open.”

Bill Bradley has made the NBA. And he is still Bill from Princeton. Like last summer, when he worked for the Office of Economic Opportunity for nothing. He doesn’t like to talk about it. But he did say, “Oh, I guess because it’s important.”

Bradley himself doesn’t think this game is much work. He thinks it’s fun, and older men will tell you those who feel that way about it—and who have the necessary and special talent—get to be the great ones.

“Who knows about him?” asks Red Auerbach, the Celtics’ general manager who won all those championships as a coach and who sat and felt uncomfortable in the Ivy League gyms just to watch him. “Maybe he is going to prove everybody wrong. They say that as great as he was in college, he’d never come close to it up here, if he made it at all. But maybe he’ll get to be a legend here, too. Maybe he just had to find out what they wanted him to do.”

Bill Bradley is, indeed, a professional now. Will he be a great one? Some people say yes, some say maybe, some say time will tell. But people who go back to the winter nights of a few years ago in Princeton’s Dillon Gym are inclined to believe that Bill Bradley can do anything he makes up his mind to do. Something like the fellow Missourian he wrote his graduate thesis about, the one who had the haberdashery there in Kansas City for a while, and never did say anything about being President.