[Our last post remembered the 1975 NBA-champion Golden State Warriors shortly after the speeches and victory parade. Now, from the Street & Smith’s 1988 Pro Basketball Magazine, here’s an even-better retrospective look at “That Championship Season.” It comes from the typewriter of Dwight Chapin, best known for his work with the Los Angeles Times. Chapin talks to all the right people, making this article a keeper for any Warrior fan.]

****

Nineteen eighty-seven. It was one of those years for Rick Barry, back in the spotlight again, center stage, the place he has always loved to be. He was elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame first, then was the willing target of a San Francisco roast that raised a whole bunch of money to benefit the Special Olympics, and just after that, his jersey—No. 24—was retired by the Golden State Warriors.

Barry, never shy, talked a lot during all of this but, perhaps surprisingly, much of what he said was not about personal accomplishment and renown, it was about a special team and a magic season, 1974-75, when the Golden State Warriors won its only NBA title.

“Without that,” said Barry, who has frequently been thought of as an All-World egotist, “none of the rest of it would mean very much. Without that championship ring, I’d still have a great void in my career.

“I’ll never forget winning the title, and the way it happened made it even more rewarding and fulfilling. The Washington Bullets were supposed to beat us four games in a row, and we beat them four games in a row. To this day, I think it’s one of the most remarkable and most overlooked achievements in the history of sport.”

Thirteen years after the fact, it’s hard to argue—just as it’s hard not to think of the Golden State Warriors of 1974-75 as a one-year wonder, a fluke. That sort of conclusion does not sit well with Alvin Attles, who coached the Warriors to the seemingly improbable title.

“I get a little angry when people label us as a freak, or an aberration,” he said. “I think it was a team that should be given the credit it deserves. To me, that season was the culmination of what coaches always try to teach: that a team that works hard enough can accomplish anything. If ever a team played to its potential—or beyond—that was the one.”

The season before (1973-74) had been a big disappointment. ”A lot of little things happened,” said Franklin Mieuli, the guy in the beard and deerstalker cap who owned the team then and had personally directed it with little success since 1963. “Nate Thurmond got hurt and then somebody else got hurt and so forth. Things just didn’t fit together.”

Then several momentous things happened. At the end of the season, Mieuli brought in Dick Vertlieb as general manager and chief executive officer and gave him approval to stir things up—the way, Mieuli said, a big old catfish stirs up minnows when it’s tossed into a bait bucket.

Vertlieb took Mieuli seriously, trading all-star center Thurmond, a San Francisco icon, to Cleveland for Clifford Ray, a first-round draft pick, and half a million dollars.

“That trade was a wrench for both Alvin and me because we both loved Nate,” Mieuli said. “Once a guy got on a gold-and-blue uniform, I loved ‘em, but I told Dick trades were okay with me if they were okay with Alvin, and Alvin said he’d agree if Dick got him a center he could play with right away.”

Unlike Thurmond, the unheralded Ray was a center who could run, and he added another vital ingredient to the mix. “The make-up of the team changed dramatically because of Clifford’s personality,” Vertlieb said. “I’ll tell you what was typical of that personality. He had a Christmas tree up in his house 12 months a year because he figured people were happiest at Christmas time, so why not be happy all the time?”

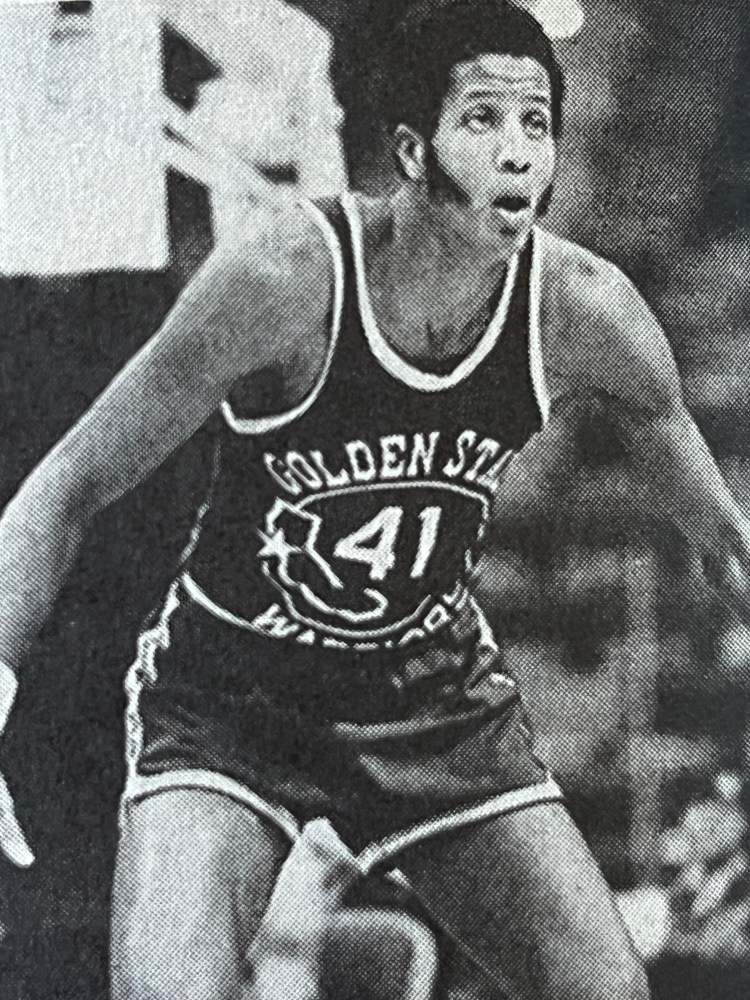

The late Bob Feerick, then the team’s director of player personnel, drafted Jamaal Wilkes (who was still just plain Keith Wilkes at the time) out of UCLA and Phil Smith out of the University of San Francisco, and Vertlieb signed them both.

Attles, meanwhile, had decided to emphasize a quick, aggressive team defense, to go along with his new running game, and employed a junior-college coach, George “Bud” Presley, to help put it in. Presley was, and is, an unorthodox sort, prone to giving advice such as, “Plague your man like a crazed, gnawing rat. DOMINATE him!”

“The man was a maniac,” Rick Barry said, “but if I were going to coach a pro team, I’d bring him in the first day of training camp to talk defense. The main reason for our success, I think, was dedication to defense, and Bud Presley was the catalyst in that. Bringing him in was probably the best coaching move Al made. It gave us the foundation to build on, and Al took it from there.”

Attles seemed to know something out of the ordinary was in the store. “He isn’t a man given to hyperbole,” Mieuli said, “but he told me at the start of the season, ‘Boss, we’ve got a good team. We can play with anybody.’”

Over the long haul, that proved true—even though the Warriors had been picked no better than fourth in the NBA’s Pacific Division. “Alvin deserves a lot of credit,” Mieuli said. “He knew that, except for Rick, there were no superstars. So he decided to play one bunch, then sit them down, and play the other bunch. He was the first guy I ever saw do that in the pros, and he never got enough credit for it.”

“I remember that veteran basketball people like Feerick and Jeff Mullins couldn’t understand what I was doing at times,” said Attles. “The conversational belief in the pros then was that you couldn’t play more than seven or eight guys and have any continuity. But I didn’t see that written in stone anyplace. I played everybody.”

Despite the innovations and the fact the Warriors came at you in waves that never seemed to quit, they hardly overwhelmed people. At the all-star break, they lost 14 of 19 games in one stretch and wound up the regular season winning just 48 games.

But this was not a team that panicked, on or off the basketball court. Forward Derrick Dickey remembers a game against the Bucks in Milwaukee over Thanksgiving weekend. “We were down 26 or 27 points,” he said, “and came back to win.”

Barry, who had been chosen team captain (the first time he had been captain of any team at any level of basketball), was having an almost superhuman season. He would finish second in the league in scoring (30.2 points a game to Bob McAdoo’s 34.5 points per game), first in free throws, first in steals, and fifth in assists.

“I never saw any athlete in any sport have a better year,” Vertlieb said.

And late in the going, Vertlieb and Attles brought in veteran forward Bill Bridges to help give the Warriors some muscle in the playoffs against Chicago and Washington. There were two other things. More subtle things. “It was a very intelligent team,” said Vertlieb, “as smart as the New York Knicks of the late 1960s, or maybe smarter. Every time Alvin called timeout, the players could adjust.

“And we were the luckiest people in the world, because we had no major injuries. It was almost as if the basketball gods looked down on us and said, ‘OK, it’s your turn; don’t screw it up.’”

During the playoffs, Vertlieb offered a little extra incentive. “He came into the locker room after a practice and said it would be nice if the younger guys could get an idea of what we were playing for,” said Dickey. “Then he opened his briefcase, which had $100,000 in it. We got the message.”

Barely. The Warriors needed six games to oust Seattle and seven to get past the Bulls in the Western Conference finals. Respect for Golden State continued to be distinctly underwhelming. “No one seemed to take us seriously,” said Attles, who made it a point never to say he thought his team would win the championship. The biggest scoffers of all, before the final series, were the members of the Washington press corps.

“The first thing we saw when we arrived in Washington,” Mieuli said, “was a headline that read, ‘The Best Team in Basketball to Play the Warriors for the Championship—Why?’”

For Mieuli, the point was not so subtly reinforced when he got to the Capital Centre in Landover, Md. “The Bullets kept seats for the visiting owners right in the middle of their hardcore season-ticket holders,” Mieuli said, “and when I walked in, someone said, ‘Hey, Franklin, Red Auerbach sat in that same seat in the playoffs last week, and you’re not going to have any better luck than he did.”

But Franklin Mieuli, for once, did have better luck than Boston’s Red Auerbach. And the Warriors had a lot better bench than the Bullets.

The Warriors trailed by 14 points in the first half of the opening game but came back to win by six, as their substitutes outscored the Bullets’ substitutes by 29 points. “There’s no question we stole that game,” Mieuli said.

The pattern, however, had been well-established. In Games Two and Three at San Francisco’s, Cow Palace, which had to be used because the Ice Follies had first call on the Oakland Coliseum, the Warrior subs outscored their Washington counterparts by 20 and 13 points, winning by one and eight. “In the second game,” said Attles, “I took the calculated risk of playing tired guys. People thought I slowed the tempo, but I didn’t.”

Defense, as it had been all season, was decisive, particularly the work guards Charles Johnson and Charles Dudley did on Bullets’ star Kevin Porter. “They were terrific,” Barry recalled. “They beat Porter to death.”

In the final, back in Landover, the Bullets again led by 14 in the first half and by eight with less than five minutes remaining in the game but lost by one, 96-95. This time, the Warrior substitutes had a 24-point edge. “I could see the fear in the Bullets’ eyes before that last game,” Barry said. “You could sense they were waiting to collapse, waiting for our bench to come in and burn them up.”

Attles wasn’t around at the end of Game 4. He sprang to Barry’s defense in a tiff with the Bullets’ Mike Riordan, got two technicals, and was tossed out. Assistant coach Joe Roberts had to take charge from there.

Franklin Mieuli had his problems, too. As the game was ending, Mieuli was in what he calls “a delightful haze of animation,” and someone had to come up to him and tell him he should be on his way to the dressing room for the championship celebration.

“But I didn’t want to leave the arena, so I stayed in my seat as long as I could,” he said. “Finally, I left and got in the queue that I thought was on the way to the locker room. Turned out it was on the way to the men’s room. When I finally got to the locker room, everybody was still celebrating, but I missed the TV cameras and most of the champagne pouring.

“Ned Irish, who was then president of the Knicks, called me later and said he and his wife had stayed up late watching on TV just to see me smiling and taking bows after all those years, and then I didn’t even show up.”

Mieuli found a way to properly celebrate later. Rather than put the championship trophy in some glass case with a guard in front of it, Mieuli lugged it around in his Triumph convertible for a year, showing it off in bars and bistros or wherever he happened to be.

“The cars backseat was too crowded for passengers, but just right for the trophy,” he said. “So I made it a people’s trophy. More people touched it that year I had it than ever before or since. We used to fill it up with beer, and everybody would scoop their glasses in it. I never worried about anyone stealing it. What would they do with a damned trophy anyway?”

Mieuli no longer is the Warriors’ principal owner but retains a minority interest in the team. “I’m a partner, just as I am in the San Francisco 49ers,” he said. “It’s a role I play well.” From that vantage point, perhaps, it’s easier to reflect.

“People used to kid me that I ran the team like a family,” he said, “and family wasn’t a good word like it is now. Back then, it meant I ran the team like a mom-and-pop grocery store. But I was kind of proud of that. I’ve never wanted to be a big shot. In the good times and the bad, I always tried to be the same. It’s hard to do that, and maybe I made an extra effort. I didn’t want to change my life or my friends or the places I went or the way I dressed.

“I think the thing I liked best about winning the championship was that it was kind of a real-life story. If this could happen to me, it could happen to anybody.”

And the others it happened to in that magic season of 1974-75?

Well, Barry and Butch Beard are sportscasters for Turner Broadcasting System and the Atlanta Hawks respectively, and Dickey is a color commentator on University of Cincinnati games when he isn’t managing J’s seafood restaurant in Cincinnati or tending his four snakes, two pythons and two boa constrictors. Mullins, the athletic director and head basketball coach at North Carolina Charlotte, which made the NCAA tournament last season. Ray is coaching with the Dallas Mavericks, and Smith is a high school coach in Escondido, Calif.

Dudley is an executive with Nordstrom department store in Seattle. Wilkes has his own Los Angeles marketing company, Smooth as Silk Enterprises. Bridges runs a Los Angeles equipment services company, and George Johnson, always elusive, spends a lot of time hitting the Bay Area’s golf courses. Nobody has heard anything of Steve Bracey in years. The Warriors couldn’t even manage to track him down for an invitation, along with the others, to Barry’s jersey retirement ceremonies last spring.

Attles, now a Warriors’ vice president, consultant, and part-time scout, admits he’s lost touch with several of the team’s players. “People who aren’t in professional sports might misunderstand,” he said, “but most teams don’t stay that close. I admire the [NFL] Raiders, because they seem to have been able to. But sometimes when you trade a player, he takes it personally. And it’s extremely rare that you find someone who has been with an organization 28 years, as I have with the Warriors.”

Old catfish Vertlieb, now working for the management of the 1990 Goodwill games in Seattle, has distanced himself from the 1974-75 players, too, although wherever he goes, he takes caricatures of each player with him to hang on his office walls.

“Winning the championship was the greatest high of my life,” he said. “The sad part is, I kind of blew myself out after that. It was never the same. This is no knock on anybody, but Franklin Mieuli is the only owner I ever worked for who was totally dedicated to winning and had total integrity when he said I could do anything—spend as much money, trade, or sign anyone and do whatever was necessary—to get a team into the NBA finals. I never met a person with the integrity of Franklin Mieuli. When I die, I want it to say on my tombstone: ‘Frankin, I owe you one.’”

Most of the players from that Warrior team came back to Oakland in March to share Barry’s emotional night. Dickey recalled it was an unusually close team. “Off the floor as well as on,” he said. “Very rarely on the pro level do you find people who are compatible and friends away from the working environment. The camaraderie we had was very rare.“

George Johnson, one of the most thoughtful of the ex-Warriors, said, “I’ve been away from here since 1977, but the chemistry is still there. I played for teams that won more games, but none that had that chemistry. I felt it again, just hanging out with the guys and going to different functions. I think my teammates felt pretty much the same. Charlie Johnson has two championship rings. I asked him about the second one, and he said it was different, not like Golden State.”

Attles has his ring in a safe. “It’s a very, very big, heavy ring,” he said. “I tried to wear it, but every time I shook hands with people, it killed my fingers.”

George Johnson didn’t wear his ring, either, for a long time. “When I was still playing for the Warriors, I tried,” he said, “but it was hard to do it, because when I got banged around, my knuckles would swell. And I didn’t want to run the risk of losing it, so most of the time I kept it in a safety deposit box.

“But when I was with the New Jersey Nets in 1984, the guys would say, ‘Hey, where’s your ring? We want to see it.’ I wasn’t playing as many minutes then, plus I wanted to inspire the younger guys—show them what playing was all about—so I started wearing it, and I wear it every day now.”

It’s a reminder of past glory, as well as a conversation piece. In the conversations, of course, a lot of people ask what happened the next season. Why didn’t the team repeat?

Perhaps it should have. The 1975-76 Warriors won 59 games and finished a whopping 16 in front in the Pacific Division. But they folded in the seventh game of the Western Conference playoff finals against Phoenix, as Barry suddenly stopped shooting. Some said it was his choice; he said his teammates wouldn’t pass him the ball. Whichever version was correct, the Warriors lost and were never the same again.

Mieuli talked about Barry, with whom he’s had a relationship of monumental highs and lows over the years, and about how tough it is to stay on top. “Rick wanted that ring so badly he was a little more pliable (in the championship season). Once he got the ring . . . but don’t blame him. He had 12 guys, all with different agendas. That’s why teams don’t repeat. You see, everybody looks for a dynasty, and every championship team thinks they have it started, but few do. It was great being there once.”

Maybe once was enough. Rick Barry, caught in the memories, seemed to think so. “It was such a fantasy-type year,” he said. “The way the guys came together and kept coming back from adversity, being underdogs all the way, accomplishing what we did in the way we did. I still don’t have the words to describe the incredible feeling I was overcome with when we won that final game, and I doubt I ever will. But if I could have only one thing to remember from my past, that year, that experience, would be what I’d pick.”

Al played for Cal Irvin at NC A&T who employed a bench system where everybody played.

LikeLike