[RIP Willis Reed, who died now 10 days ago. Here’s a long tribute to The Captain and his truly class act. The article comes from the February 1973 issue of SPORT Magazine and profiles Reed rejoining the Knicks after a season on the mend. It’s a really nice profile penned by the great Jeff Greenfield, who, of course, later transitioned to network television and covering national politics.]

****

Willis Reed moved into the circle casually, ready to begin the work he had been doing for half of his life; the Sacred Heart medal swung easily against his chest as he shook hands and exchanged a word or two with his rival center. The program listed Reed at 6-feet-10, 240 pounds, but standing next to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, he seemed dwarfed by at least half a foot.

The capacity crowd at Madison Square Garden had booed Abdul-Jabbar and cheered the New York Knick captain, but the cheers seemed tinged with doubt. Always in the past in this setting, the Knicks and their leader had taken the measure of the Bucks and Abdul-Jabbar—eight straight times the Knicks had won at home—but this November day in 1972, two overwhelming handicaps were burdening New York. First, Jerry Lucas, who had helped the Knicks win the Eastern Division title the previous season, was sitting on the bench in a double-knit suit, sidelined with an ankle injury.

Second, Willis Reed was only slowly, uncertainly working his way back from a year away from basketball, and two years away from full physical health. For weeks, murmurs of doubt—even from his admirers—had accompanied Reed’s struggle.

A poor performance against his strongest rival would swell the whispers to a chorus: “Willis will never be back.”

****

A sports arena is a kind of decontamination chamber; entering a football or basketball stadium, we banish for a few hours the ambiguities, betrayals, and disappointments of life; we except as a given the simplicities of Absolute Good and Total Evil. Men who spend their days at jobs which weary the body or bore the spirit, men who sell goods and services of uncertain worth, can find on a Thursday night or a Sunday afternoon a source of unwavering enthusiasm. For once, there are no doubts. The familiar young men in the home uniforms are good; the strangers in the visiting costumes are evil.

That is why so much of our thinking and talking about sports is surrounded by mythology. In sports, excellence is acknowledged and honored. Greatness in other fields—Industry, politics, literature—is constantly challenged by muckrakers, historians, critics. But an achievement in athletics stands by itself as an outsized deed. A no-hitter, a hat-trick, a 40-point night is an event to be cheered, celebrated, and remembered without the intrusion of voices suggesting that what we saw and cheered did not really happen.

Willis Reed became a legend at the age of 28 on the night of May 8, 1970, between 7:15 and 7:45 p.m., in the moments just before and after the start of the game that decided the championship of the National Basketball Association. It was a time when the last shockwaves of the 1960s were battering America: The invasion of Cambodia, massive confrontation at Yale, the killing of four students at Kent State University in Ohio. Some act of affirmation, something without pain and bloodshed, had to happen. For New York, it happened when Willis Reed, crippled by a thigh injury suffered in the fifth game of the Knick-Los Angeles Lakers finals, limped out of the locker room to join his teammates on the court. The Knicks fans, whose cheers and chants were adrenaline to their heroes and hemlock to their foes, cheered his practice shots, his warm-up passes. Had Reed knelt to tie his sneaker laces, they would have cheered that, too.

Willis Reed scored the first basket of the game, on a one-hand shot from the top of the key. He scored the second New York basket from 20 feet out. He did not score again. He did not have to. With Willis’ presence supplying the emotional surge and Walt Frazier hitting five straight baskets, the Knicks ripped the game apart. It was 17-8 midway through the first quarter; 61-37 when Willis rested with three minutes left in the half. At the final buzzer, the Knicks had won, 113-99, and New York had its first championship in the 24-year history of the club.

As F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote of Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight, a man “did a heroic thing, and for a moment people set down their glasses in country clubs and speakeasies and thought of their old best dreams.”

Now, two and a half years later, his body on the downward side of the metabolic cycle, Willis Reed was matching his skills and his will against another, darker Fitzgerald insight: “In America, there are no second acts.”

Reed somehow controlled the tap against Abdul-Jabbar, and the fans cheered with surprised delight. Willis fed forward Dave DeBusschere, who missed, the rebound going to Milwaukee. The Bucks worked the ball downcourt, like some huge yet oddly delicate flamingo, Kareem took a pass, arched his body, hooked the ball over Reed, downward, into the basket. And already the crowd was muttering, “How is Willis gonna stop that guy? How can he do the job?

The struggle of Willis Reed in the autumn of 1972, and the two years of pain and incapacity that had followed the 1970 championship, had provided the first break in a succession of achievement extending from Madison Square Garden back to a high school in Bernice, Louisiana, where Willis was raised, the only child of a construction worker. It started when the high school coach saw the 13-year-old for the first time.

“How tall are you?” the coach asked Reed.

“Six-five,” Willis said.

“I don’t believe it,” the coach said, marching him over to the gym for a measurement. After the tape convinced the coach that he was not dreaming, Willis Reed began playing basketball in earnest, and always, playing to meet a self-imposed standard of excellence. (“I don’t play to please people,” he says. “I play to please myself.”)

His Grambling College coach, Fred Hobdy, recalls he once told Reed after an indifferent performance that he would never play pro basketball. Reed wept and wiped out Grambling’s next opponent. When he was named the Knicks’ second-round draft choice in 1964 (Jim Barnes was first), the slight rankled for years afterwards.

“I didn’t believe there were eight guys better than me,” he says.

Willis proved his worth his first year with 1,175 rebounds, a 19.5 scoring average, and the selection as Rookie of the Year and member of the NBA All-Star squad (an honor he won every year until he was forced by injury to sit out the 1971-72 season).

Reed is the only member of the 1964-65 team still with New York, and he is in that sense the beginning of the modern Knicks, the Knicks as consistent contenders. When Reed arrived, New York was in the midst of a 10-year debacle: Between 1956 and 1966, the Knicks finished last nine times, compiling a record for the decade of 292 wins and 478 losses. With the acquisition of center Walt Bellamy in 1965, Willis moved to an unaccustomed forward position, where he averaged close to 20 points a season—but the Knicks continued to lose.

Slowly, however, the nucleus of a great basketball team was gathering. From Baltimore in 1965: Guard Dick Barnett, bent with age (he was almost 30), with a side jump-shot whose accuracy was insured when Dick’s legs tucked all the way under his body. From Princeton and Oxford in 1967: Forward Bill Bradley, whose student body president’s face contorted into agonized effort as he ran ceaselessly back and forth, waiting for the open shot that sooner or later would come. From Southern Illinois University that same year: Walt Frazier, the poet of the court, moving to a rhythm only he heard, a small smile suggesting self-appreciation, eyes looking for the least hesitation by an opposing ballhandler, hands waiting to steal and break. From the Knicks’ own organization came coach Red Holzman in December 1967, drilling a sense of teamplay into the minds of his players: See the ball, hit the open man, get to practice on time. The Knicks have not missed the playoffs since Holzman’s reign began.

Finally on December 19, 1968, came the move that fused the Knicks together and gave Willis Reed the chance for greatness. Dave DeBusschere came to New York from Detroit in exchange for Walt Bellamy and Howard Komives. DeBusschere joined Bradley at the forwards; Willis Reed went back to center. And now, playing in the pivot with his back to the basket, Reed began to show that remarkable versatility that made him unique among big men.

There was his shooting, exceptionally accurate for a center; his soft jumper was deadly within 15 feet, and the fact that he shot left-handed confounded his opponents. Other centers, used to blocking the lane on defense, faced an unpleasant choice: Stay inside and let Reed shoot uncontested, or move out and open the middle for the drives of Bradley, DeBusschere, and Frazier.

There was his bulk, making him especially effective in setting picks. Willis would move to one side of the key; the forwards and guards would run their man into Reed, then spring free for drives or shots. And if they were double-teamed, there was always Reed’s outside shooting.

And there was his defense. Bill Bradley describes it: “He’s the big man backing up our mistake. He produces ‘the Russell effect,’ like Chamberlain or Jabbar or Thurmond. What that means is you take more of a chance because if your man slips through for a backdoor, Willis is there.”

After DeBusschere joined the Knicks and liberated Reed, New York went 36-11 through the rest of the 1968-69 season, defeated the favored Baltimore Bullets four straight in the opening playoff round and lost to the Boston Celtics in six games only when Walt Frazier was slowed by a groin injury. The next season, the Knicks won it all—and Reed did, too. With 1,755 points and 1,126 rebounds, with 426 playoff points, with his high-noon seventh game heroics, Reed was the king, waiting a triple-crown most valuable player parlay—for the regular season, the playoff games, and the All-Star game.

And then, it all came apart.

The Knicks moved downcourt, Willis running hard, moving to the right of the key, with Abdul-Jabbar’s huge arm poised in front of him like a railroad gate. Reed moved left, took a pass, and hit a faraway jump-shot to tie the score 2-all. The cheer exploded again when Willis rebounded off the offensive boards a minute later. Then the silence began to grow. The Knicks were missing; the Bucks were hitting. Abdul-Jabbar was fouled by Reed and sank two; 30 seconds later, Kareem broke for the basket, took an Oscar Robertson pass, and slammed it through. With barely three and a half minutes gone, Milwaukee led, 14-3.

“It is such a drastic thing that happened.” Reed was sitting in the team bus, his legs jammed up against his chest, talking of the past as the Knicks drove through the gloom of New Jersey on the way to a certain win over the Philadelphia 76ers. (The team, I suspect, is named after its average attendance.)

All through 1970-71, Reed’s left knee was bothering him. It was tendonitis, an inflammation which restricted his running and jumping. Then, in the playoffs against Atlanta, Reed was hit hard by Walt Bellamy—the man he had displaced in New York. Reed could average only 12 points through the playoffs; the Knicks lost in the semifinals to Baltimore.

“I had an operation and felt that everything would be all right,” Willis recalled. “And then, to find that the knee still hurt and that my career might possibly be over . . .” He shook his head, remembering.

He had played the first six games of the 1971-72 season, but the knee wasn’t right. He couldn’t drive, couldn’t jump, couldn’t leap for the rebounds. After a 30-minute stint against Houston in late October, he sat out two weeks. Against Cincinnati, he played 12 minutes. Then, after a half against Golden State on November 11, he was taken out.

Reed did not play another game that season. Instead, he sat at the scorer’s table in street clothes, watching the Knicks adjust to playing without him. Luckily for New York, Jerry Lucas had been acquired from the Warriors in the offseason for Cazzie Russell. Lucas moved into the pivot; and although at 6-feet-8 he was small for a center, his remarkable shot from 20 feet and further and his quick adjustment to the Knick offense helped New York reach the NBA finals. While the Knicks lost in five games to the Los Angeles Lakers, an injury to Dave DeBusschere left open the question of whether the Knicks without Reed might still have gone all the way. For Reed, the success of his team was clouded by uncertainty about his own future.

“I got paid,” Willis said, “but I didn’t want to be paid that way. An article came out about me taking over as coach and Red becoming general manager. I didn’t want to coach. To play, that’s where you have to have those special skills. It’s such a special thing to get to be a professional basketball player . . . I’m not about to give that away as long as I can offer something.”

So, in the spring of 1972, Willis Reed began the long road back. “My leg was put in a walking cast for six weeks, and I did semi-isometrics. Then I started with a weightlifting program for my leg, up to about 35 pounds.” By September, when training camp opened, Willis was running.

Although a thigh injury, unrelated to the tendinitis, kept Willis out of the first five games of the season, he was back with the Knicks, feeling his way back to the rhythm of the team, reviving the instincts he had not tested for almost a year. Watching him on the basketball court, you could begin to make judgments about when—and whether—Willis would come all the way back. But talking with him, talking about him to teammates and rivals, you would realize that Reed had on his side an asset that did not show in statistics or in battles for a rebound: The asset of a remarkable personality and character.

Now, it was the Knicks’ turn to move. Earl Monroe hit from the baseline, seemingly balancing himself on a mid-air platform. Then Reed got free, moving to the basket, taking DeBusschere’s pass and laying it in. On defense, Willis kept his right shoulder against Abdul-Jabbar’s left; from the courtside, you could see Reed’s eyes peering intently over Kareem’s shoulder, searching out the ball. While Kareem waited to drive or hook, Dave DeBusschere backed casually away from Bob Dandridge and threw his right hand at the ball, knocking it away from Abdul-Jabbar. The Knicks controlled, broke, and Frazier fired to DeBusschere who hit. New York scored 10 straight points, cutting the lead to 14-13. The Bucks called a timeout, and the Garden fans were standing already.

Willis Reed fits no mold. To describe him—and to suggest the reasons for the respect and affection in which he is held—is to echo the cliches of public relations men peddling the virtues of their clients. The words that make sense are curiously old-fashioned. They sound almost quaint in a time when sports is spelled with a $, when tax shelters count for more than 50 years of a city’s loyalty, and when 19-year-olds pore over the details of income averaging and pension plans. The words for Willis Reed are words like endurance, pride, dignity, obligation, and aristocratic.

He fits no ready pattern. He is wealthy; between his six-figure Knick salary, his summer basketball camp, his Harlem liquor store, and other investments, he makes a few hundred thousand dollars a year. But his wealth is not flaunted. There is no $1.5 million home in the mountains of California, no llama rugs. There is instead a two-bedroom, $285 a-month apartment in Rego Park, Queens.

He is Black, and his pride is intense. He once took a technical after shouting at a referee, explaining to a teammate, “That man told me to shut up. Nobody tells me to shut up.” When a white policeman arrested Willis at gunpoint last summer, claiming Reed had threatened him when the policeman had stopped Reed’s car, Willis spent time and money proving his innocence.

But there is no sense of hostility, none of the stony silence of a Duane Thomas, the moodiness of a Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the militancy of Dock Ellis. He is instead unfailingly patient, outgoing. If a man who makes his living in the trench warfare of the basketball pivot can be called gentle, that is what Reed suggests.

He is single now, divorced from the woman he married in college, with a nine-year-old son and a six-year-old daughter who live with their mother in Louisiana. (“It wasn’t another woman. It was this way of life, and the fact that I was going in the directions that she just did not want to follow.”) He is attracted to women and not inclined toward celibacy. But there are no Joe Namath-Derek Sanderson exploits, no circular beds and clever innuendos spread across the newspapers. Willis Reed’s pleasures, like his politics and his personality, are essentially private. Indeed, among his deepest drives is a longing for solitude and tranquility.

****

He talks with enthusiasm of his love of hunting. “I guess it’s the thrill of being alone in the woods, a sense of being able to outwit game. And there’s the beauty of game animals. The last two years, I’ve been out West; bagged a white bear, black bear, antelope, and elk.

“It wasn’t just shooting. I like to travel. Hunt, fish, camp out, live off the fat of the land.” As we passed the oil refineries for New Jersey, Reed seemed to be talking about another world.

“Professional sports is a pressure cooker kind of business. You’re always at airports, catching buses, three, four times a week. And that’s not the kind of travel that I like to do. I like to get in my jeep, pack a tent and camping gear, look at my map, and just go . . . a week, a month, whatever I feel like. ‘They’re so free.’ Of course, they haven’t got any responsibilities either. But that’s how I like to travel. At my pace, with no pressure.”

New York City is not exactly Reed’s ideal of where to live. “New York is a very angry town. No one trusts you, no one’s friendly, you say to yourself, ‘What does he want, what’s his angle?’”

Willis talks excitedly about a dairy farm he recently bought in Pennsylvania—276 acres of rolling hills and woods with “some of the best deer hunting in the East.”

“Look,” I finally said to Reed. “You seem to love hunting, traveling, rural life. But financially, you could do that right now—as much as you wanted. Why do you play any more ball, if you can live the way you want to live?”

Willis frowned and shook his head. “That would be like leaving a job that’s undone,” he said. “I haven’t played my career out, and I’ll play until I haven’t any more to give to the game. There are too many people now who don’t make maximum use of their talents. They forgot what it was like going to bed not knowing if there’d be enough to get by on tomorrow. I wouldn’t be satisfied getting paid the money I’ve gotten and not doing as well as I can.”

The quarter ended on a note of promise for New York; with four seconds left, Bradley took a pass from Frazier and hit a jumper, giving the Knicks a 23-22 lead, their first lead of the night.

Perhaps the hex that had struck Milwaukee so often here in New York might be working again. And perhaps Reed might manage to neutralize Abdul-Jabbar’s power, might muscle him away from the boards and open the middle. Perhaps.

The pursuit of excellence is a passion of Reed’s. He plays with complete commitment; he respects it in those who play against him. Nate Thurmond, of the Golden State Warriors, is a player Reed admires for his level of play. But the basketball player Willis speaks of with the most obvious respect is Bill Russell, the ex-center and coach of the Boston Celtics.

“When I started playing seriously in high school, Bill was just starting to play pro ball. I was especially interested in him because, like me, he was from Louisiana, he was left-handed, and he was a center.”

Reed grinned suddenly, breaking into laughter.

“I remember my first year in the pros, we went up to Boston. We called a timeout, and I told Eddie [Donovan, the Knick coach], ‘I think I figured Russell out; I can handle him.’ I noticed he wouldn’t go for the first fake . . . you’d move, and he’d just stand there. I figured I’d fake twice.”

Reed laughed again. “So, I go out there . . . and I go once—twice—and wham! Russell blocks the shot. Now, I really had him figured out: You don’t fake at all. You just go right up. So, I go right up. Wham! Russel blocks it again! I told myself, ‘I’m gonna make sure that he’s over there when I’m over here.’

“Oh, yeah, he was the top. He could block shots, rebound, play defense. And he was a leader. He had so much pride—he played to win.”

It is this combination of qualities that gave Reed—playing at his peak—his stature. Beyond the basketball skills, Reed suggests a sense of absolute effort. “Our one indispensable man,” DeBusschere called Willis in his book, The Open Man.

“Willis’ leadership is substance, not a myth,” says Bradley, whose political interests make him at least a quasi-authority on leadership. “Sometimes, leadership is not perceived even by the people who are being led. Willis has perceived leadership.”

The fusion of Reed’s own pride and his role as team leader sometimes has led to violence—on and off the court. In his second year in the NBA, playing against St. Louis, Willis suddenly became incensed at the rough play and single-handedly attacked the Hawk bench. One swing sent half the bench sprawling; the other half became disciples of non-violence.

“That’s part of his leadership,” Bradley says. “When there’s a fight on the floor, Willis will be there to protect us. I know that sounds absurd, because we’re all big, but it’s there. He is the guy who’ll smash into Jabbar, to help open the game for the team. Without him, that doesn’t happen.

The Knicks began the second quarter by widening their lead. Although Reed had not scored since sinking a layup in the first quarter, his picks were freeing Monroe and Bradley, and Willis was screening Kareem out under the Milwaukee boards. When he left the game midway in the second quarter, the Knicks had a 36-30 lead. When the first half ended, the score was tied at 42-all.

Statistically, the Reed-Abdul-Jabbar matchup was a rout: The Buck giant had 16 points and 10 rebounds to Reed’s six points and five rebounds. But the strength and presence of Reed, the quality that had been absent for so long, was beginning to make itself felt.

“People who recognize me on the street ask me two things—the same two things—without fail,” observed Phil Jackson. “First, ‘Are ya gonna win tonight?’ Second, ‘How’s Willis doing?’”

If the Knick forward could legitimately plead ignorance about the first question, a two-week period last November provided an uncertain answer to the second.

Statistically, Willis was far off his form. A combination of limited playing time and rustiness had cut Reed’s scoring; his 7.0 scoring average was barely a third of his 20-point career average. A year away from the game had clouded Reed’s instincts; he frequently bobbled passes and got his hands on rebounds only to lose them into the hands of opponents. Most significantly, while Reed looked strong against weak opponents—he played 33 minutes and scored 17 points against Portland—he seemed ineffectual against teams with established pivot men.

In Oakland on November 4, Nate Thurmond of the Warriors outfought Willis consistently. Five days later against the Atlanta Hawks in New York, Reed made his first start since November 11, 1971. He played almost the entire first half against Walt Bellamy, and, in their worst 24 minutes of the season, the Knicks fell behind, 57-34. Without having scored a single point, Willis sat on the bench in the second half as New York, with Jerry Lucas at center, stormed back to win, 101-99. Two days after the Atlanta game, he played only five minutes, again went scoreless, and watched Golden State win, 103-102.

****

While the state of Willis Reed’s ability was of concern to fans and the team, it was not an urgent issue. Jerry Lucas was performing well at center; New York had lost to only two teams (the Warriors had beaten them twice), and a playoff spot seemed a certainty. Reed could take his time getting back, with no cost to the team.

That changed radically after the loss to Golden State, when Lucas came up with an injured ankle. For at least three games, Reed would be on his own, with no one to spell him except the rookie Gianelli. “How’s Willis doing?” became a question with a more anxious tone.

“He’s not running downcourt as fast as he used to,” said Nate Thurmond after the Warriors’ overtime victory. “Three-quarters of Reed’s points used to come from the inside—and the moves aren’t there now. But it’s just like anybody else—you know, Muhammad Ali’s the greatest fighter in the world, but you lay off for three years, you got to wait for your timing to come back. I tell you, I really hope he makes it back.”

Connie Hawkins, the Phoenix Suns forward who nursed a bad leg while in the ABA, spoke of his own comeback. “A lot of it is up here,” Hawkins said, pointing to his head. “I remember I’d find myself reacting with hesitation lots of times. A guy would bump my leg moving past me, and I’d jump. It takes a while.”

Connie had some more thoughts after watching Willis score one of six baskets for a two-point total in 29 minutes of play. “He blocked a lot of shots,” Hawkins commented, “and he played a decent game. But he’s not the Willis Reed he used to be. He can’t seem to make the moves anymore. He used to have this fake, where he’d get down low and then get free for the jump. You’ve got to go in traffic, and he’s not going yet.”

Coach Red Holzman was philosophical. “His shooting is improving, but it’s still not where it should be,” Holzman said one day after practice at the Pace College gym. “He’s coming along, but to remove all doubt, he’s got to keep doing it. I tend to be optimistic about it. I think he’s on his way back. Remember, Willis is a guy with lots and lots of pride. When he was healthy, he was a superstar. So, the standard for him is a lot higher than for somebody else. But we know what he did—and we think we know what he can do.”

In the third quarter, the Bucks broke the game wide open. Abdul-Jabbar’s hook shot over Reed 14 seconds into the second half foreshadowed what was to come. In the first 4:13 of the third quarter, only Frazier’s jump-shot put any points on the Knick side of the scoreboard. Once Kareem, standing alone under the basket, sent the backboard shuddering with a stuff. When Reed left, after committing his fourth personal foul, Milwaukee held a 58-48 lead.

Three and a half minutes later, the lead had grown to 70-50. At one point, Abdul-Jabbar leaped from the lane like some prehistoric beast rising from the primordial slime; the right hand rose, clutching the ball easily, firing it downward on a hook straight through the hoop. And on the Knick bench, right leg drawn up, left leg stretched full length, chin on fist, Willis Reed watched the most-importance test of the year slipping silently, certainly away from him.

You could see the hesitation: Reed, taking a pass in the pivot, faked Walt Bellamy, then held up, just long enough for the path to the basket to close. Reed, holding up while the crowd screamed, “Drive!” or “Shoot!” or “Go, Willis!”—faked left, right, left, and then passing off. Reed, holding the ball over his head, suddenly whipping a pass to the baseline—which bounced out of bounds as Earl Monroe did not break.

Rustiness? Or something more permanent, beyond the capacity of will to overcome? Willis Reed was past 30 now, and in the compressed lifespan of athletics that is to be past middle-age. It is a time when the body begins to betray its promises of youth, a time when the infinite resilience and boundless energy start to become less dependable certainties.

How long would it take for Willis to fully regain his own confidence, to regain it at the level of instinct, where the mind confirms that the body’s capacity to leap, jump, shoot, drive? What if the continuing hesitations and mistakes spawned new doubts in Reed’s mind? What if the lost year and the loss of youth convinced Reed that he could no longer meet his own high standards?

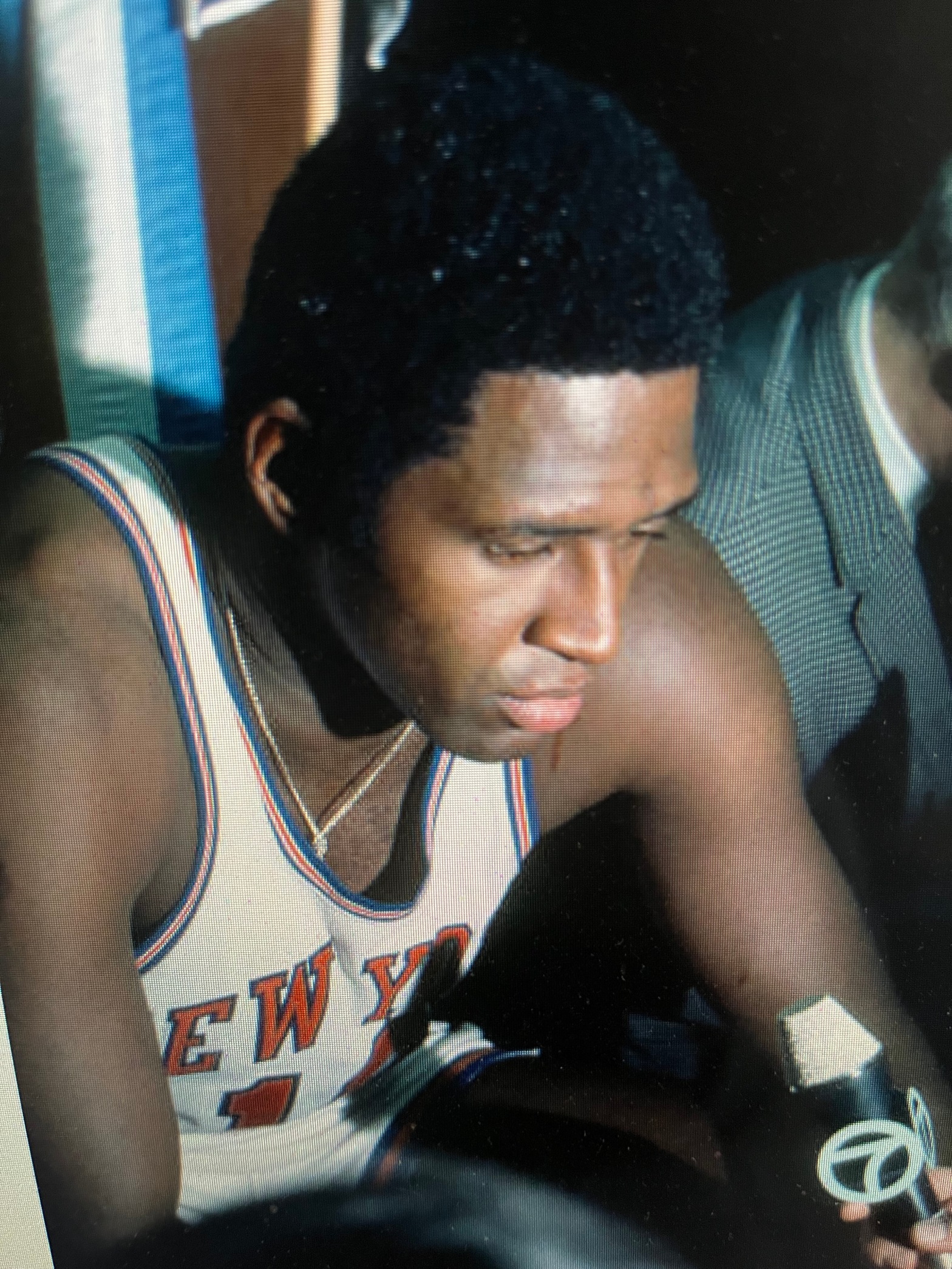

After each game, he would sit on his stool in the New York locker room, an ice pack held to his left knee, as he methodically stripped the tape off his feet. He was usually the last Knick to strip off his uniform and shower; he answered the questions of reporters quietly, assessing himself with detachment.

“I’m not shooting as well as I should be . . . I understand what Red’s doing, Lucas played real well tonight . . . Offense is a very delicate thing; you have to be sharp to the nth degree . . . It’s all a question of getting back into the flow of the game.”

Only once in the early weeks of the season did he betray a flash of impatience. After a five-minute stint in the losing effort against Golden State, he began to speak of sitting on the bench, watching his team lose in overtime. “It’s frustrating, just sitting here,” Willis said. “You have to have that playing time to get back into the game . . .” He stopped, shrugged.

Two nights before he was to face with Abdul-Jabbar, the newsmen crowded around his locker, asking him again and again: Are you ready for Kareem? Can you stop him? After 10 minutes of this, Willis finally looked up. “It’s part of my job. If I had my way, I’d go out and play against junior high school kids.”

Willis came back into the game with 8:10 to play and New York down, 80-64; and while he managed to slip by Abdul-Jabbar for a reverse lay-in, Kareem came back with his unstoppable hook from the lane. With 5:50 left, Dandridge hit a jumper, and the score was 86-68—an 18-point Milwaukee lead with less than six minutes to go. Only a miracle could save New York—and Reed—from losing their first critical test of the season.

You get a glimpse of Reed’s strong sense of personal values when you talk to him about money. He has it, and he works to keep it, reading about real estate and tax shelters and the wider world. (“I got a stake in this country now. What happens affects me—and my money.”) But, like a true aristocrat, he is skeptical about sudden wealth, and fully aware of the fusion of talent and fate that brought him from hauling hay and picking cotton in rural Louisiana to affluence.

“I had no idea I’d ever be making this much money,” Reed said over a cheeseburger at a Howard Johnson’s on the New Jersey turnpike. “I used to think, ‘If I could ever make $25,000 or $50,000 a year . . .’ That’s the most I ever hoped for.

“I was good. But I was also lucky. I always tell kids and their parents, ‘Don’t push to become a professional athlete. There’s so few of them . . . the possibility of becoming one is so remote.’

“Look,” Reed said. “Think of how many kids are in high schools right now, dreaming of playing in the pros. Think of how many of them will never even go to college, much less play on a team. Okay. Now think of those that get to college. How many of them will ever get a look from the pros? It’s like watching traffic in New York, with 300 cars trying to get into the same place. There’s a guy in high school now who may really be good, but he’s going to find he’s not so great, because there’s another kid who’s been practicing harder. That’s why in the long run professional athletics is a losing proposition.”

He talked about the way athletic skills can turn a poor man into a rich man with astonishing speed. “Because I make more money than the garbage collector, that doesn’t mean I’m better. One of the things that’s wrong is that big businessmen and big criminals wear good suits, have nice homes, and they’re doing more to hurt people than the guy who goes into a store and sticks it up for bread ‘cause he’s hungry.

“I came from a home as poor as anybody could be. If I could ever forget that, I wouldn’t be very much of a human being.”

Reed knows, too, that the skills which have won him affluence will not last forever. “There are certain tastes I have not acquired. I don’t want to acquire them. And I don’t like to buy on credit. So, if I don’t make that much a few years from now, it won’t be the end of the world.”

It began when Earl Monroe drove for a lay-up and was fouled by Lucius Allen. After the three-point play, the Knicks intercepted a Bob Dandridge pass and Frazier drove for the basket. It was 86-73, but less than five minutes remained. Suddenly, it was the Bucks who could not score, and Willis Reed with putting his bulk against Abdul-Jabbar’s back, forcing him out beyond the 16-foot line, beyond the limit of his shooting accuracy. Frazier hit again on a jumper, and then Bradley fed Monroe. The Buck offense faltered; Frazier forced a Robertson fumble, and Earl Monroe hit again. Then Chuck Terry was tied up; New York controlled the tap, and DeBusschere sank a 20-foot one-hander from the right. Suddenly, with 2:23 left in the game, Milwaukee’s lead was down to 86-81. Milwaukee called time, and the Garden shook with the crowd’s roar, as Reed slapped his teammates on the back and clenched his fist.

“Everybody wants to know what I’m going to do when I stop playing. In the first place, I’m not ready to stop playing. In the second place, I don’t know. I do know I’d like to be involved in something that would . . .” He looked for the right words. “. . . something that would be important.”

He seems indifferent to coaching, but Reed has the instincts of a teacher. He makes it a practice to room with rookies on the road. “He’ll spent a lot of time helping me out,” says Henry Bibby, the Knicks’ third-round draft choice from UCLA. “We live near each other, and we drive home from practice together. Willis’ll talk about what we’re doing right and wrong.”

“You wanna know what kind of guy Willis Reed is?” asks Henry Scroeder, who works at the Madison Square Garden press lounge and spends a part of his summer working at Reed’s camp. “Most of the guys who work at his camp are college kids, who want to try and make the pros. Willis watches them, and after the last scrimmage each day, he’ll come back to the gym with one kid—who’s really worked hard—and he’ll spend two hours teaching him moves under the basket. He’s one of the few guys who runs a basketball camp who’s really there, all the time.”

Reed’s affection for kids is genuine. He gives 18 scholarships to his basketball camp in the summer, and he has spent time promoting New York’s Police Basketball League, where street kids can compete in tournaments.

****

If Reed’s future lies in part in teaching (he was a physical education major with a minor in biology at Grambling), it also lies in part with the land. An hour before he was to face Milwaukee and Kareem, he was showing a stack of color snapshots of his Pennsylvania property.

“Here’s the road that marks the property line . . . Here’s where I plan to put the house . . . We’re going to put a lake there . . .” He looked at the fall foliage, the sloping hills, the snapshots of himself and friends displaying their fishing catches.

“It’s quite a piece of property,” he sighed. He put the pictures in his travel bag and laced up his sneakers, getting ready to go out and play basketball against Abdul-Jabbar.

Some of the fans were standing now as time went back in. The Bucks could not move the ball inside as Reed kept forcing Abdul-Jabbar out. Reed took the rebound off a long missed shot, passed to Bradley, who fed Monroe at the right of the key. The shot never touched the rim, as it zipped through. The score now 86-83, Reed was hawking Abdul-Jabbar, daring him to drive or shoot. Kareem’s shot missed, and Reed took the rebound again. Frazier dribbled downcourt, shot, missed.

Bradley picked up the ball in a crowd, fed Frazier who drove and was fouled, barely missing a three-point play. As Clyde stepped up to the line, it sounded as if 19,694 people were moaning with anticipation. Frazier hit both fouls. Milwaukee called timeout. Then it was Robertson in-bounding.

A whistle. Earl Monroe, battling for position with Lucius Allen, had pushed too hard. And because the foul came before the pass-in, it was a two-shot foul—two shots which could win the game.

The fans started hollering, screaming, seeking to impose the jinx that almost never worked. Allen’s first free-throw bounced off the rim. Now, there was a chance for overtime. Allen shot again. The ball hit the rim and dropped off. And from the right of the lane, Willis Reed swooped under the basket, controlling the ball with his left hand, landing, turning, giving the ball to Frazier. A pass to Monroe. A jump-shot. Cleanly through. The Knicks led, 87-86, with 36 seconds to go. But somehow, between the now-intolerable crowd noise and their determination to hold the ball as long as possible, the Knicks never shot. Bradley was still looking for room when the 24-second buzzer sounded with two seconds left in the game.

Everyone in the Garden knew what the last play of the game would be: A long inbounds pass to Abdul-Jabbar as close to the basket as possible. And there was Willis Reed, forcing the Buck center outside, using the muscle and the presence that were supposed to be gone. With Phil Jackson windmilling in front of Lucius Allen, the pass reached Kareem more than 15 feet from the basket. His hook wasn’t even close—and the buzzer sounded.

The crush around Reed’s locker suggested the announcement of a Presidential candidacy. In between the questions and the whoops of joy from the Knicks, unbelieving players and writers swapped statistics. Yes, the Bucks did not score a point in the last five minutes and 50 seconds. Yes, New York had scored the last 19 points of the game. Yes, it was now nine straight victories at the Garden against one of the strongest teams in NBA history.

And over and over, Reed answered the same questions now with barely contained satisfaction. No, I wasn’t getting too tired toward the end. Yes, my main point was to keep Abdul-Jabbar at least a foot further out from the three-second lane, where he likes to shoot.

“It was not just a victory for the Knicks,” Frazier said. “It was a big victory for Willis.”

****

Sometime later, when the press had gone, Reed sat with his icepack on his left knee, slowly pulling the tape from his feet. Friends were waiting: A postgame drink at a nearby restaurant, conversation, relaxation.

Reed smiled.

“Tomorrow, I’m going hunting in Westchester. Quail, pheasant. Deer hunting season opens Wednesday. This’ll be the first time I’ll miss it in a long time. But maybe I can manage to get in a day of deer hunting sometime next week.”

As Reed’s thoughts left the arena of the job he has, the job he means to do better than anyone else, toward the arena of private ease, the ghost of F. Scott Fitzgerald may have been re-thinking his maxim. For while the timing needed work, and the blocking wasn’t quite right, it looked as if the curtain was starting to rise on Willis Reed’s second act.