[Bob Cousy had his reservations about the aging, ball-dominant Oscar Robertson while coaching the Cincinnati Royals at the end of the 1960s. But Cousy was less reserved about the Big O earlier in the decade. The Cooz thought the young Royals’ star was the best thing going in an NBA backcourt and the bellwether for a “new breed” of player that was bigger, stronger, and more multitalented than in the 1950s. He explains more in this article published in Dell Sports’ 1964-65 Basketball annual. The article, written by Associated Press reporter Bob Hoobing, also includes perspective on Robertson’s body of work and finishes with some extra analysis and oh-wows from Red Auerbach and NBA stars Clyde Lovellette and Tom Gola. Take a look.]

****

“Oscar Robertson is the best backcourtman to come into the league since I’ve been playing. In fact, I think he’s probably the best all-around player in the game right now.”

This praise comes from the summit . . . Bob Cousy, retired all-time playmaker of the National Basketball Association. He labels Cincinnati’s Big O: “the best of a new breed.”

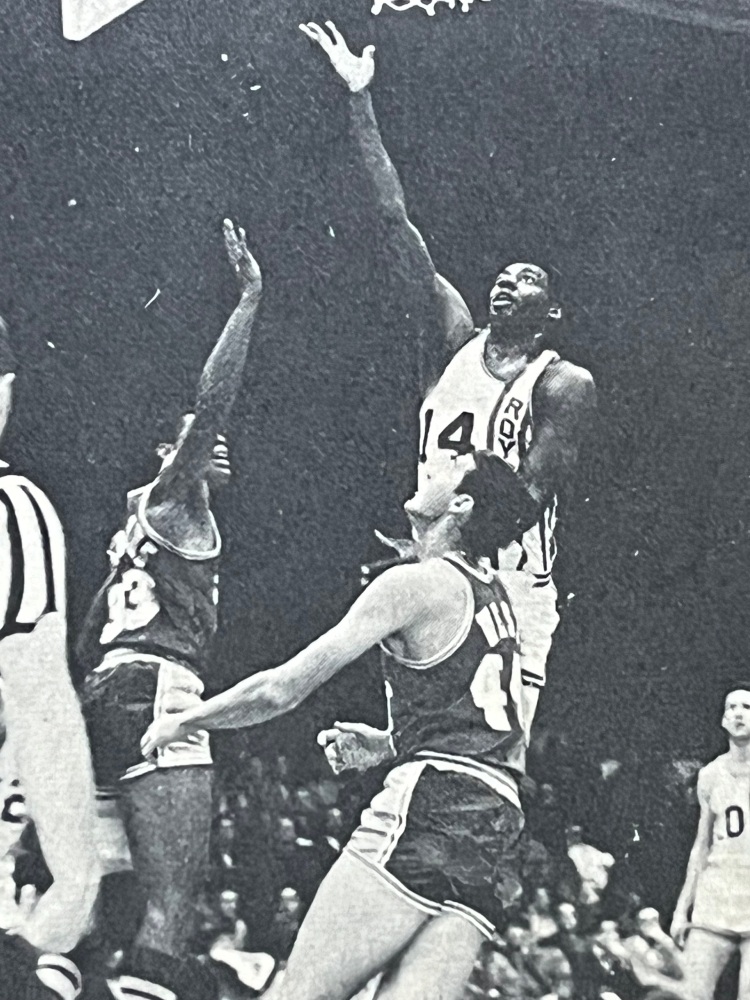

In just four seasons, Robertson completed the journey from the NBA’s Rookie of the Year to its Most Valuable Player by vote of his fellow athletes. What’s more, he made the trip with superstars like Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell, and Elgin Baylor as roadblocks.

Not since Dr. James Naismith knocked the bottoms out of a couple of peach baskets has there been a guard such as Cousy so qualified to comment on the performance of another backcourt great.

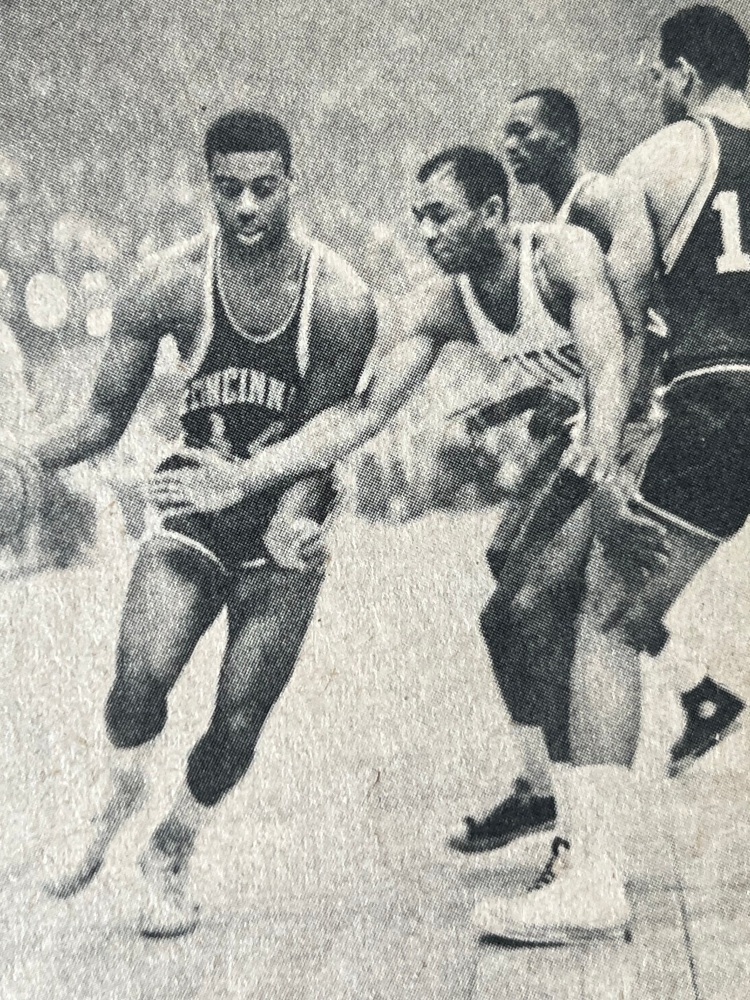

Cousy, the current coach at Boston College, repeatedly proved over a 13-year pro span why he was the greatest court magician since Merlin. With his assortment of full-court, blind, and behind-the-back passes, Cousy was the master at setting up a play. Although he was never a scorer to the degree Robertson is, Cousy’s 16,955 points rank him third in NBA career totals. He also had 6,949 assists, leading the league for eight straight years in that category over one stretch.

“There have been attempts made to compare Oscar and me,” said Cousy, pausing in the heavy press of demands at his summer camp in New Hampshire. “You might say such efforts are unfair to both of us.

“There’s no yardstick. We don’t play the same kind of game, really. Oscar can probably do things I never could because of his superior height. I could do some things, perhaps, he never can. It holds true both ways.

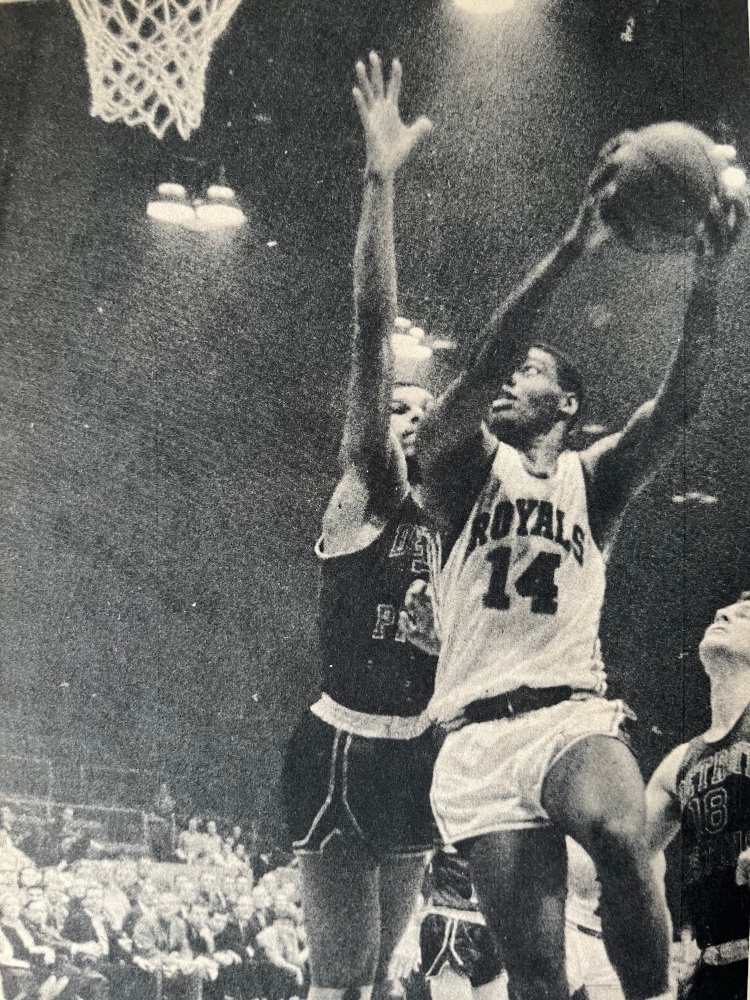

“I think Robertson is probably the best all-around player in the league right now. I’m talking about all phases of the game. If you’re considering positions, of course, Russell is all alone at center. Forwards begin with Baylor and Bob Pettit and go on from there.

“As for guards, Oscar is pretty much the dominant figure. From every standpoint, I think Robertson can do more things—and do them well—than anyone else in the game. You never stop being impressed by him . . .

“Don’t forget Robertson is 6-5. That means he’s taller than some pretty fair forwards like Frank Ramsey, Cliff Hagan, and Paul Arizin. It’s a good four inches taller than guards like Bill Sharman and myself and an even bigger margin over Guy Rodgers and Slater Martin.

“I think that in another decade, there won’t be anyone under 6-5 in the league. Jerry West may be listed as 6-3, but he’s closer to 6-5. Boston’s John Havlicek also is 6-5. Richie Guerin, Arlen Bockhorn, Sam Jones, Dick Barnett, and Rod Hundley are just about as tall.

“Robertson is the all-around best. There may be better players at one of two things. But no one comes really close to him when you add everything up. Just think about it for a minute. Consider Oscar’s ability and versatility, then add in his strength and height to go with it.

“Unless he’s seriously injured, Oscar will reach 10,000 points fairly early this season (he has 9,341 and a 30.1 average for four years). Only a handful of guards in the history of the league ever attained that figure. And only Guerin managed it in under 10 years.

“No, Robertson doesn’t have a weakness. There’s only one thing I’d like to see him do more of as far as playmaking is concerned. I’d like to see him develop the play a little more, set things up more with passes. He passes now out of necessity rather than trying to set up a play. He has a tendency to keep the ball, but on the other hand, he has such fantastic ability to put it in the hoop that it’s not a fault.

“However, when you have the ball so much, like I did, you have to come down the floor, thinking only of setting up a play, looking for an opening, and getting off the pass that opens up opportunities.

“As far as his playmaking goes, Oscar has the ability in every respect to be great if he just changed his thinking. Then again, if his playmaking improves, his role as a great scorer—and his points—may suffer. He just has a tendency to hold the ball a little too long. That’s the only thing I can think of, and that’s really scraping the bottom of the barrel looking for something.

“Obviously, you’re never going to get a perfect player. Oscar certainly rates as the next best thing. If any of the Royals resent the fact Robertson shoots a lot, I haven’t heard about it.

“No game emphasizes teamwork as much as basketball. When players get unhappy with a teammate, for any reason, it soon shows up on the scoreboard, then in the standings. Look at the way, Cincinnati pressed the Celtics most of the season in the Eastern Division race. Robertson does the job. He couldn’t be better.”

****

At 27, the Big O has an almost limitless future. From college All-American and U.S. Olympic team champion honors in 1960, Robertson stepped onto the first team All-NBA in 1961 and hasn’t budged from it since. Last spring, the vote was unanimous.

In the player balloting for league MVP, Oscar was fifth his rookie year, third each of the next two seasons, and won in 1963-64. He was runner-up to Wilt Chamberlain in scoring last season after being in the number three spot each of the previous three campaigns. Over his short career, he has amassed 3,215 assists and averages better than 800 rebounds per year.

Robertson has an enviable All-Star Game record. No team on which he played has lost. He sparked the West to victory in 1961 and 1962. Then, when the Royals were realigned in the Eastern Division, Oscar led his new mates last January. He paced all competitors in points (26), assists (8), field goals (10), and minutes played (42). In his rookie year, he was voted the game’s MVP and repeated the honor in the most-recent classic.

Robertson thrives on pressure. In the 1963 Eastern Division title playoffs, he was held to 14 points by Boston’s Sam Jones in the first half. The Big O came back with 29 after intermission, hitting on 68 percent of his field goal tries and paced a 135-132 upset. That was only the opener of a series in which the Robertson-fired Royals went the full seven games before the Celtics could pull it out.

It wasn’t Oscar’s fault Cincinnati lasted only five games in the same division showdown last spring. Boston was super-charged, the Royals’ Jerry Lucas was far off form, and Cincinnati was no match for the Celtics off the bench.

Boston coach Red Auerbach paid Oscar this glowing tribute: “That Robertson keeps you on your toes until the final buzzer. He never lets up. There is nobody like him for that. You know, Oscar is so great that he scares me. He can beat you all by himself.”

Cousy’s reference to Robertson’s passing was underscored after the 1964 playoff opener when Cincinnati coach Jack McMahon commented: “Oscar is not making us run the way we should. Sure, we need his scoring, but we need his playmaking, too.”

Later, it was discovered Robertson had pulled a tendon in his right, or shooting, wrist. Oscar and Russell—who voted for each other for MVP—remained the dominant figures of the division playoffs throughout.

“I thought the Celtics did the best job ever on Robertson defensively,” Cousy said. “They interchanged K.C. Jones and Havlicek covering him. Both are strong and aggressive. They just wore him down.”

During the series, K.C. Jones explained the defensive plot: “Our strategy is to try to keep the ball away from Robertson. We must play between Robertson and the ball at all times. Then his teammates must either pass to someone else or gamble on a high pass to try to get it to him.

Oscar’s favorite play is to bring the ball right down the court, pick up a screen, and shoot. We can hamper this. Then it’s up to the man being screened to break through and pick him up.”

****

Of course, Cousy is not the only veteran player impressed by the Big O.

“Playing the Baylors or Pettits is tough, but Robertson has that way of tormenting everyone on the floor,” says Clyde Lovellette. “Neither Baylor nor Pettit can handle the ball too well. Once they have it, they’ll shoot, and you can make some sort of adjustment. But Oscar works so many ways, he’s practically unplayable.”

“Robertson is the only guy I’ve ever seen who can go under and make a layup on Russell and Wilt Chamberlain,” adds Tom Gola.

“Oscar is the greatest,” Cousy states. “There are none better.”

That’s the word from the man who wrote the book on the position that both play so well.