[Phil Berger was a proud New Yorker and an avowed basketball nut. He also was a fantastic journalist who wrote some of the best material about pro basketball and its brightest stars, from the late-1960s onward. That includes this March 1969 profile of Oscar Robertson from the magazine Complete Sports. It repeats a lot of what’s already known about Robertson, but after all these years, the story is still worth reading for pulling together all the threads of the Big O’s NBA career as of the late 1960s and just before the Bob Cousy’s arrival and rebuild in Cincinnati. With that, Phil Berger.]

****

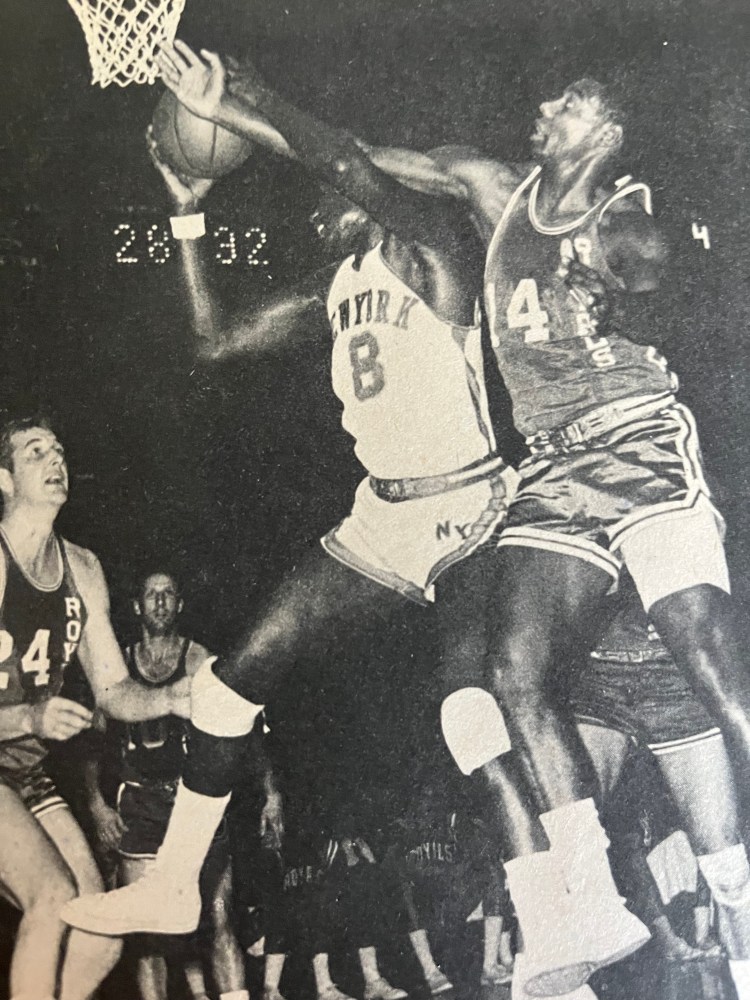

The best description of Oscar Robertson’s basketball philosophy was made by a man who has had to play against him for a living. Dick Barnett, the New York Knicks’ fine guard, said it colorfully:

“Oscar’s tough. If you give him a 12-foot shot, he’ll work on you until he’s got a 10-foot shot. Give him 10, he wants eight. Give him eight, he wants six. Give him six, he wants four. Give him four, he wants two. Give him two, you know what he wants? That’s right, baby. A layup.”

As Barnett implies, Robertson is never satisfied that he can’t do better. Any time the Big O—as Robertson is referred to—laces on his sneakers, he’s out to prove he can make things look even easier on the court.

“I have the feeling,” said Yvonne Robertson, Oscar’s wife and number-one fan, “that he’s competing against himself now, even more than against another player or a team. Just to see how much better he can be, how he can do something a little differently, and still do it well. Just to keep accomplishing and improving.”

It is true. Robertson is a perfectionist. Whenever the subject is basketball, the Big O wants to be the best, the absolute best. A few seasons ago, Jack McMahon, who was then coaching the Cincinnati Royals, tried to make practice more interesting for the team by holding a foul-shooting contest. McMahon offered a $5 prize for the man who hit the most of 25 free throws. Three Royals promptly made 23 of 25 shots, one of them being Adrian Smith, who once shot .903 percent from the foul line over the course of a season. But neither Smith nor the other Royals collected McMahon’s prize simply because Robertson stepped to the line and commenced to get 25 consecutive foul shots. It was typical of Robertson. He always manages to be just a little better than the next guy—even in practice.

It is not just natural ability that makes the Big O so great. More important is the way he applies it. “Oscar,” said Wilt Chamberlain, “is not as fast as some ballplayers or as good a shooter as others. But he knows how to put everything together better than anybody else.”

What makes Oscar the best all-round player—and few argue that point—is his competitive drive, his instinct to be artistically perfect on the court. Listen to Oscar talk about as simple a basketball act as passing, and you get an idea of how he is about the game: “All passes aren’t good passes just because the ball reaches the teammate that you intend it for. If the man has got himself into a good shooting position and your pass pulls him out of it, it’s a bad pass. That’s what playmaking really is, getting the ball to the man so that he’s in position to take his best shot.”

Though Robertson’s lifetime statistics are outstanding (he has averaged over 30 points per game and about 10 rebounds and 10 assists a game), many pros think that he could score more if he were so inclined. Oscar’s own teammate, Jerry Lucas, said, “If Oscar ever really sets out to see how many points he could score in a single game, there’s no telling how high he can go.”

But personal glory is not Robertson’s big concern. Winning ballgames is and, to that end, the 6-5, 218-pound Royal tries to keep his teammates involved in the action. Said ex-New York Knicks coach Dick McGuire: “I’ve seen Oscar concentrate on passing. He’ll make sure that each of the Royals get a bucket in the first couple of minutes. Then they’re all happy, and they play together. Actually, the only time he’ll concentrate on scoring is when they’re behind.”

Or, when he’s angry. NBA coaches advise their players not to arouse the Big O’s temper. It just doesn’t pay. In the 1966-67 season, a Chicago Bull rookie named Jerry Sloan blocked a shot by Robertson and ended up regretting it. Recalled the then-Bulls’ assistant coach Al Bianchi: “Suddenly, Oscar wasn’t dribbling anymore. He was pounding the ball into the floor like a piledriver and moving deliberately toward the basket, time after time, pouring through point after point . . . Now I’ve got a standing order on my club. When Oscar’s mad and starts for the basket, I want the three nearest guys to forget their own men and help out.”

Even a mild-tempered Robertson is a big problem to the opposition. When Red Auerbach was coaching the Boston Celtics, there was one season when the Celtics couldn’t seem to hold Oscar to less than 40 points a game. Auerbach would devise different strategies to limit the Big O’s scoring output, but it always ended up the same—Oscar scored 40 points or more.

Finally, Boston held Robertson to 37 points, and Auerbach jokingly said: “We tried something new on him. I told the boys to stretch their fingers out wide, with their hands way up on defense, figuring every little bit helps. But you know what Oscar did? He shot through their fingers.”

When Auerbach was coaching, the Celtics used to rotate three guards against Oscar, the speedy Sam Jones, the persistent defensive specialist K.C. Jones, and rugged John Havlicek. The idea was to try and wear down the Big O. Generally, it didn’t work. Auerbach’s successor as coach, Bill Russell, has abandoned such elaborate strategy. “I don’t think it makes a bit of difference who’s covering Oscar,” he said. “You just don’t stop Oscar. The way we work it here now, I let the guards decide that among themselves. The way they’ve worked it out, the one with the worst excuse gets him.”

If Robertson is now everybody’s idea of the perfect ballplayer, there was a time when it wasn’t quite that easy. Living on the West Side of Indianapolis, Oscar can remember playing on a peach-basket hoop in back of this family’s paper-roofed house. He and his older brother Bailey used a rag ball held together by an elastic, or—if they were lucky—an old tennis ball found in the neighborhood alley. When the brothers graduated from the backyard, the younger Oscar wasn’t always permitted to play with the bigger boys which—quite naturally—angered him.

“I promised myself,” he said, “that I’d get so good that they’d have to let me play. I practiced all the time. I practiced at the Y and at what was called the ‘Dust Bowl,’ which was just a little vacant lot a couple of blocks from our house.”

Wherever Oscar went, he travelled with a basketball, that’s how much he was hooked on the game. “He was always bouncing it,” his mother remembered. “He’d bring it to the dinner table, and he took it to bed with him. When the sound of the bumping stopped, we knew that Oscar was ready to go to sleep.”

It wasn’t long before Robertson was playing with the bigger boys. In fact, he soon was playing better than any of them. He led his high school team, Crispus Attucks, to two straight titles and 45 consecutive victories.

“It was a great thrill,” Oscar said, remembering the first title. After the game, the local fire department was there with the firetruck, and we all got aboard and rode through town with the siren going, and then we had a bonfire and everything. It was sort of inspiring. It really was.”

Robertson played college ball at the University of Cincinnati. When he was a sophomore, he came to Madison Square Garden in New York, and proceeded to amaze everybody by scoring 56 points. During his college career, Robertson shot the ball often, but his teammates never begrudged him his shots. “Oscar made us a team,” said teammate Ralph Davis. “He can do anything.”

One night, the club was watching Oscar receive a postseason award on television, and they heard him say, “It’s nice to make All-American, but I couldn’t have done it without the help of my teammates.” That was when a Cincinnati player, Mike Mendenhall, jumped up and hollered at the screen, “The hell you couldn’t.” Later, Mendenhall would tell a reporter: “He is the greatest. Just the greatest. There isn’t a bit of jealousy. I even enjoyed practices. He’s that enjoyable to play with.”

Robertson’s teammates with the NBA Cincinnati Royals were not quite as enthusiastic at first about him, basketball being a game in which five ambitions have to make do with one ball. In Robertson’s rookie season (1960-61), Cincinnati’s attack was—one writer put it—“as complex as a baby’s rattle: Robertson took the ball inbounds, thumped down the floor until he saw a shot or passed off to set up a play.”

The dribbling annoyed his teammates, one of whom said, “I think we’ve got to run to win. We can’t bull our way against these other teams with their big men. We just don’t have the big men. If the defenses get set up, we have trouble rebounding. If Oscar bounces the ball deliberately, fooling around until he sees an opening or a screen, we can get killed off the boards.”

But the Royals—despite their initial doubts—discovered a funny thing about Oscar: When they managed to elude defenders, the Big O somehow would get them the ball. Pretty soon, they stopped complaining about his dribbling and shooting.

Not that Oscar ever stopped shooting. He didn’t. In his rookie season, he averaged 30.5 points per game and was named to the All-NBA team at the end of the season—a remarkable feat for a rookie. Since then, Oscar’s seasonal average has never varied more than two points on either side of 30, which prompted one long-time basketball expert to say: “If Oscar walked into your neighborhood playground for a pick-up game, he’d probably get his 30 and not much more. He’s the most-consistent star ever.”

That consistency is willed by Robertson. He’s obviously capable of getting more points if he wants. But Oscar is such a brilliant playmaker (“the only real playmaker to come into the league for a while,” according to Bob Cousy), that he does not have to score to make Cincinnati’s attack go. By forcing the defense to converge on him, he can then pass to the Royal who has been left free for the easy shot.

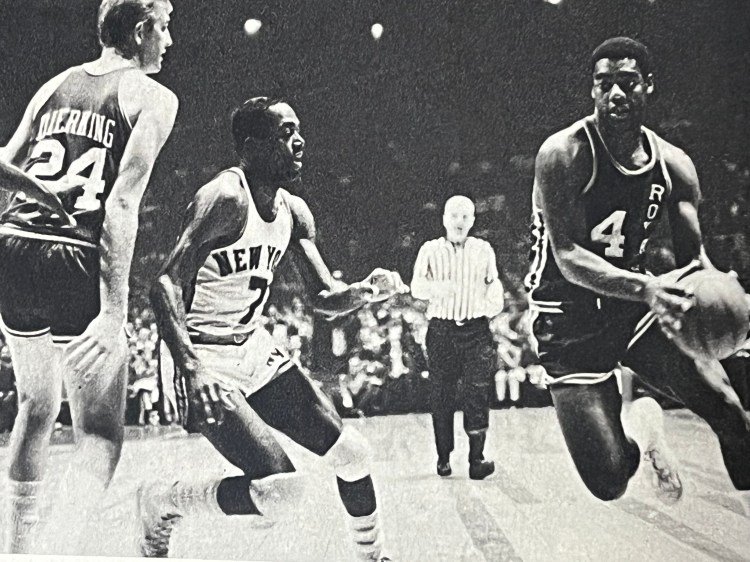

A good example of Oscar’s playmaking knack is the case of veteran center Connie Dierking. In his first six seasons in the NBA, the 6-10, 222-pound Dierking had averaged a meager 6.9 points per game. But coming to the Royals a few seasons ago, Dierking grew used to working with the Big O. He learned that if he made precise moves to shake free of his defender, Robertson would get the ball to him, and he would score more points. So, in the 1967-68 season, Dierking worked hard to get open and left the rest to Oscar. The result? Dierking averaged 16.4 points per game—more than he’s averaged during his entire pro career.

For all Robertson does for his teammates, he is not hesitant to scold them for mistakes. That is the Big O’s way. As writer Ed Linn said: “As soon as he steps onto the court, the man who had seemed so mild and easy-going, begins to crackle with intensity . . . When anything goes wrong, a look of sheer disbelief comes to Oscar’s face. He yells at his teammates, assuming complete command. If the play turns sloppy, both fists shoot into the air, and he cries out, “What the hell is going on here!”

It is as ex-Royal coach McMahon says, “He’s the boss man out there. He is the leader. He’s giving those guys hell, believe me, and they take it, too. He’s a very intense player, burning up inside every minute.”

This is the perfectionist streak in the Big O, a trait of his that even leads him to criticize the referees when they make a questionable call. “That sportsmanship stuff is fine,” Oscar said. “But winning is all that matters, because they haven’t stopped keeping score yet—and they won’t. As long as you win, that’s all people really care about. You get no points for sportsmanship.”

Actually, Robertson is not as coldhearted as it sounds. Jackie Moreland, who used to play with the Detroit Pistons, recalled the time his team lost so many guards because of injuries that he suddenly had to shift from forward to a backcourt spot. His defensive assignment? Oscar.

“I had a bad leg myself,” Moreland said, “and Oscar knew it. But he didn’t try to make me look bad. He passed off a lot. I probably couldn’t play him very well on two legs. But the fact that he didn’t try to take advantage impressed me more than anything about him.”

That Oscar didn’t try to exploit Moreland’s injury is typical of him. As a perfectionist, he has no need for cheap baskets. The Big O is always trying to prove himself on the court. To take advantage of Moreland would have proved nothing. Besides, the Big O has too much respect for his fellow pros to rub it in on one of them. A perfectionist does his best against the best.

And against the best, Robertson is in complete control. He dribbles the ball rat-a-tat (“like it’s on a rubber string,” says Lucas), turning his back to the man, maneuvering closer and closer to the basket until he either has the easy shot he wants or has created a situation where one of his teammates is open for an easy shot.

“No matter who he’s playing with or who he’s playing against,” said ex-NBA star, Tom Gola, “Oscar controls the game. Oscar makes the difference. Oscar is the best ever!”